West Philadelphia’s Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) is an iconic minimalist space renowned for white and glass exteriors and cool linear insides. Starting July 13, however, ICA opens its doors and its floors to the mossy, messy, eclectic exhibition ‘Where I Learned to Look: Art from the Yard.’

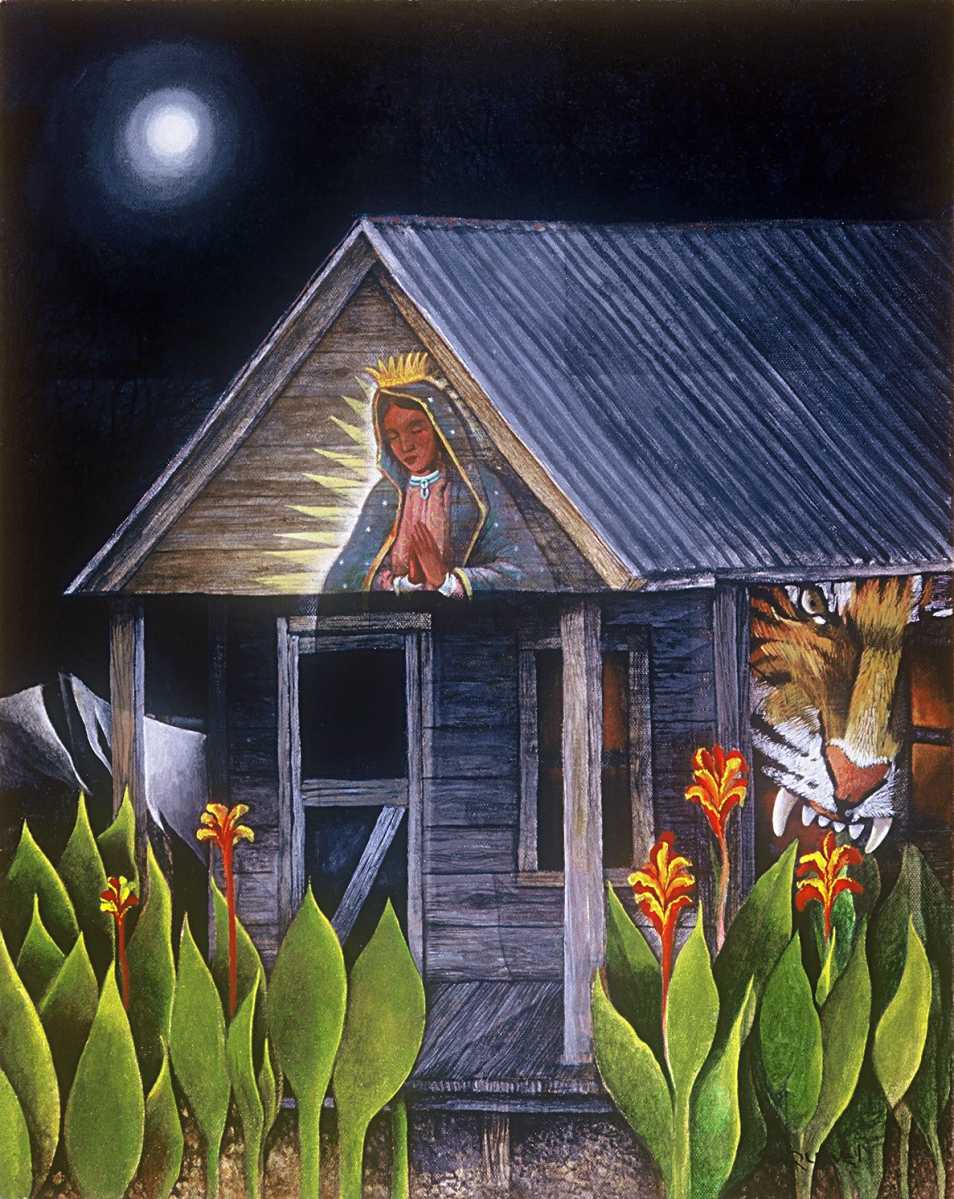

Here, 30+ artists display the “lineage and legacy of yard art” while adding their own fresh, funky perspectives as to what yard aestheticism brings to the weight of contemporary art. Curated by artist and art historian Josh T Franco, this exhibition presents the idea of one’s grassy knoll as an “intermediary space between public and private” that artists use for self-expression.

Franco sat down with Metro to talk more about inspirations, possibilities and why yard art is so special.

What’s your definition of yard art – the challenge you posed to avant-garde artists like Jeff Koons?

The yard is the space between one’s home and the wider world. That can range from palatial aristocratic estates of Europe where gazing balls were first put on display, to the strip of sidewalk between the street and the front door of a rowhouse in Baltimore. Three works here are set in reservations (or reserves, as they’re called in Canada), and have anchored conversation about state-sanctioned Indigenous territories; I’ve been asking the artists, myself, and others, rather than ‘What is a yard?’, ‘Whose yard is North American?’

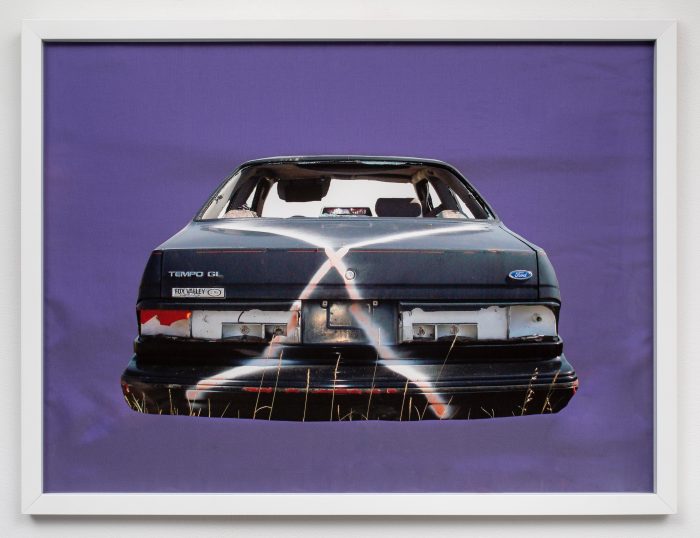

This show also recognizes artistic and functional innovations that’ve taken place in yards and become a visual language appropriated by studio-and gallery-based artists. In this context, canonical artists like Koons and are not necessarily avant-garde, as they’re framed. Koons stated that the gazing ball sculptures and paintings are partly inspired by a memory of a neighbor’s yard growing up in Pennsylvania. I doubt the maker of that gazing ball is known, but it’s possible Koons’ series would not exist without it. Set in the center of the gallery, the gazing ball serves the function it would in a yard: to reflect its environs, including you, in 360 degrees.

How did you answer your own challenge with your windmill made by your grandfather, Hipolito Hernandez, and a site-specific snake of white marble rocks?

My art historian training did not begin in my AP art history class in high school, which was my narrative for a long time. If the basis of an art historian’s work is close-looking, then my training began in childhood, playing in my grandfather’s yard. He was a prolific, playful maker, always creating things out of a network of small sheds in his backyard, using poured cement, found objects, salvaged playground equipment, old tires, and other materials to create this colorful, warm, and fun outdoor environment for our family.

His windmill in the show, which I took from his yard after he died, is a perfect example of his work. His yard was always changing too, so we had to be attentive, lest we miss something. It’s been transformative, de-centering museums, universities, and other institutions that have shaped my profile as an art historian in favor of recognizing the significance of my grandfather’s yard in my formation. I hope this show encourages others to reconsider the yards that populate their own life narratives.

As a West Texas native, how do you believe that your epic skies widen your take on scale and space when it comes this exhibition?

Thank you for acknowledging the powerful open sky and horizon line of West Texas. It truly is the most beautiful sky in the world, in my biased opinion. I’m always relieved to arrive back home; everywhere else in the world feels claustrophobic by comparison. Visitors to this show will be greeted immediately to their right by a video shot in Marfa, Texas. While the video is focused pretty tightly on the activity of preparing a backyard altar, the West Texas sky is in the background.

One of the aspects of yard-based and outdoor artmaking in that setting is that—while you might be working on something small and intimate—this dramatic, all-encompassing sky provides a constant backdrop. I know from friends who grew up in very wooded, hilly, or urban settings, that the first time encountering the West Texas sky can be disorienting and unsettling. For me, it feels like freedom and possibility, like I can do whatever I want because the big sky makes room for everything. “Do whatever you want” is also an ethos of yard art I’ve observed during the development of this exhibition.

What was your criteria for commissioning Art from the Yard’s contributors?

I’m an organic, gut-driven, instinctual thinker who lets personal relationships inform decisions. That’s reflected here: David Driskell and Clarke Bedford were/are neighbors. I worked with Finnegan Shannon at Judd Foundation with personal connection to Judd and Shannon’s work. I dug into research – I am a scholar – looking at catalogs of past yard art exhibitions and archival materials.

Discovering that someone named “Nancy” sent artist Beverly Buchanan photographs of Detroit’s Heidelberg Project was remarkable. Buchanan is a yard artist in my mind, and Heidelberg is an oft-cited exemplar. That these sources weave their distinct visual languages together is a stunning confluence, and I’m thrilled to share these with audiences, so don’t skip the documents case.

This exhibition also owes much to Lynne Cooke’s Outliers and American Vanguard Art at the National Gallery. That show was revelatory, especially when facing the challenge of bringing in works whose original environments are radically different than the ICA’s white cube. My co-organizers at ICA are great collaborators in building this list; Hallie Ringle introduced me to Allison Janae Hamilton’s work, and Denise Ryner connected us with the rad BUSH Gallery crew. Of course, there are dozens, if not hundreds of, other great artists who could be in a show about yard art. I hope more yard art shows happen.

‘Where I Learned to Look: Art from the Yard’ opens at the Institute of Contemporary Art, at 118 S. 36th St., on Saturday, July 13. For more information, visit icaphila.org