More than four years after City Council passed legislation banning the use of synthetic herbicides in parks and playgrounds, Philadelphia’s Parks and Recreation department is still applying tons of the chemicals every year.

The Healthy Outdoor Public Space law, approved in December 2020, prohibited the weed-killing substances and mandated that the city government move toward an organic approach, citing herbicides’ associations with asthma, cancer, birth defects and other health issues. A waiver process was enshrined into the statue to allow for exceptions.

Jim Kenney, the mayor at the time, declined to sign the bill, arguing that Council had overstepped its authority by attempting to dictate how publicly-owned property is managed. Attorneys in Mayor Cherelle Parker’s administration reiterated that language in a meeting last week, Councilmember Cindy Bass, the law’s author, said.

Kenney committed to posting signage before applying herbicides; not using the chemicals within 50 feet of play equipment; conducting a trial of organic products; and implementing a pesticide reporting system.

Parks and Recreation Commissioner Susan Slawson, during a hearing about the HOPS Law Tuesday morning, told lawmakers that her department has been upholding those promises.

But Council members want the Parker administration to do more to bring the city into compliance. If they do not act, Bass brought up the potential of filing a case in court, and her colleague, Jim Harrity, has floated legislation creating a misdemeanor criminal charge for the use of synthetic herbicides in public parks.

“I’d rather see us do it voluntarily, so that there is none of this back-and-forth bickering,” Harrity, who organized Tuesday’s hearing, told Metro. “We have some nuclear options.”

Three years ago, organic products were tested to control vegetation at Germantown’s Fernhill Park, but the approach was not effective, Slawson said.

AeLin Compton, environmental restoration crew chief for the department’s natural lands team, testified that the organic compounds were unable to kill down to the roots. Invasive plants often returned within two or three weeks, she said.

“From my use of those products, they’re essentially a chemical mow,” Compton added. “There’s no difference than going out and using a weed whacker.”

She explained that Parks and Recreation employees and contractors are required to follow the instructions on a product’s label. Additional protective equipment is available if requested, according to Compton.

Only herbicides approved by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency are permitted, department officials told Council.

Warning signs are posted before chemicals are applied and remain up until the area is dry, typically 24 hours after depending on weather, said Sue Buck, deputy Parks and Recreation commissioner for operations.

Compton said Philadelphia’s wooded areas are “sick,” inundated with invasive species that are killing trees. Some of the problematic plants cannot even be removed by using machinery or pulling them out, she added.

“There is no single magic bullet approach that will replace this really critical tool,” she said, referring to synthetic herbicides.

Parks and Recreation deployed 15.64 tons of product across the city in 2023, the most recent year for which data is available.

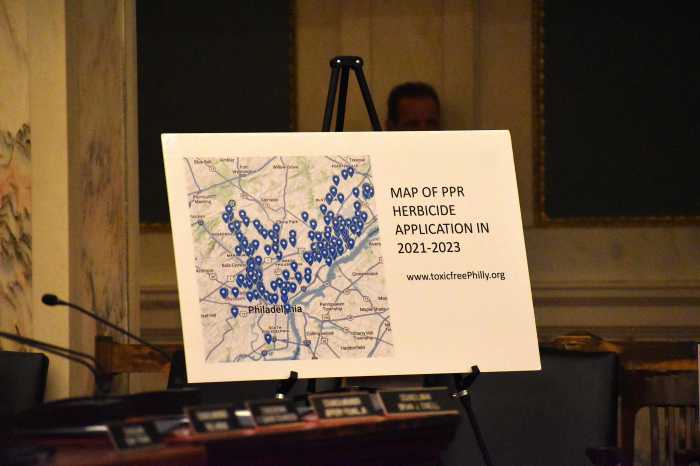

Toxic Free Philly, an organization pushing to end the use of synthetic herbicides, put together a map of parks and playgrounds where the substances have been applied in recent years. It is available at toxicfreephilly.org.

While a number of chemicals are involved, advocates highlighted the department’s use of glyphosate, first marketed as Roundup, and 2,4-D – one of the ingredients in Agent Orange, infamously used during the Vietnam War.

“There are no established safe levels of herbicides, and children are uniquely vulnerable to health effects from that exposure,” testified Linda Stern, a doctor who has treated patients at the Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center. “These chemicals can remain in the soil for many weeks, even months.”

Nasir Lewin recounted growing up playing basketball at Lonnie Young Recreation Center in East Germantown. At 14, he was diagnosed with leukemia and underwent 45 blood transfusions and nine operations while hospitalized for more than a year.

“We don’t know for sure, but if there’s any chance the herbicides sprayed on the courts to control weeds caused my cancer, there’s no good reason to keep using them,” said Lewin, now 19 and in remission for the past three years. “I wouldn’t want anyone else to go through what I’ve gone through.”

Bucks, the deputy Parks and Recreation commissioner, suggested doubling the buffer between the chemicals and play equipment and no longer using herbicides on ball fields. Harrity, meanwhile, discussed paying teenagers to pull up weeds as part of a summer jobs horticulture program.

The issue is personal for the at-large Council member. A longtime member of the Laborers’ union, Harrity has worked spraying herbicides in the past, and his father is a disabled Vietnam veteran dealing with the impacts of Agent Orange.

“My question is how much does a child cost nowadays?” he said at the beginning of the hearing. “What is the life of a child worth? For me it’s worth everything.”

Slawson committed to coming up with an herbicide plan, likely starting with just a sliver of the department’s 10,000-plus acres.

“This seems extremely urgent, and I feel like our plans take a long time, often,” Councilmember Rue Landau said. “Plans are only as fast as the urgency of the leaders behind them. So I would love to see something come up immediately.”

“We’re not going to drag our feet on this,” Slawson later responded. “Next year, you will not sit here, and we haven’t moved.”