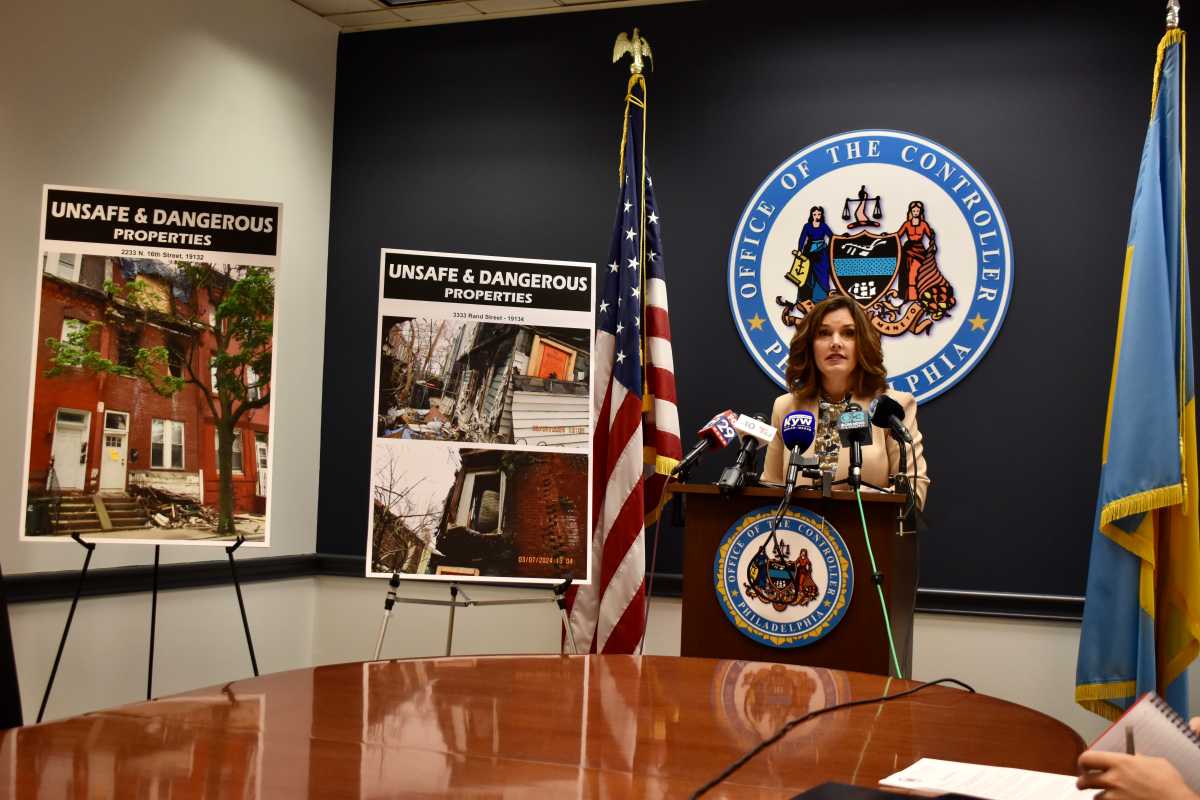

Philadelphia’s Department of Licenses and Inspections does not have enough staff to monitor buildings considered unsafe and at risk of collapse, according to a report released Wednesday by City Controller Christy Brady.

In another finding from the investigation, L&I is only recouping 3% of the cost of city-ordered demolitions, which are supposed to be billed to the property owner.

“We cannot wait for the next tragedy to occur,” Brady said at a news conference. “We must protect our homes and our communities.”

The 14-page report, which includes photographs of buildings determined to be “imminently dangerous,” is based on a review of L&I’s online database, budget, interviews with employees and on-site property inspections, the controller’s office said.

It was the first of a “series of investigations” into L&I planned by the controller’s office, said Brady, who was sworn in for her first full term in January.

“When I was campaigning for election to this office last year, one of the things I heard over and over was the concern homeowners had about the demolition work taking place in their neighborhoods,” she said. “Particularly in rowhome properties that are built side-by-side and can be catastrophically affected when unsafe demolition is performed on a building next store.”

Brady also described the report as another “ripple effect” from the 2013 Center City building collapse that killed six people who were inside a Salvation Army store.

She said the unit in charge of tracking unsafe and dangerous structures is budgeted for 20 inspectors but currently has only 15 – the lowest staffing level since at least 2020, according to the report.

When the investigation was conducted earlier this spring, their caseload included 120 imminently dangerous buildings, which post a risk to the public and must be frequently inspected, and about 4,000 properties classified as unsafe. Due to the potential safety implications, an inspector is ‘on-call’ 24/7.

L&I hires contractors to demolish hundreds of dangerous properties every year, paying $25,000 to $30,000 for an average two-story home, according to the controller’s report. The bill is sent to the owner of the land, and a lien is placed on the property.

Analyzing four years’ worth of data, Brady’s office found that L&I spent $60 million to knock down nearly 2,000 properties and only recovered $1.8 million from owners. She said there is “no process” for collecting the funds.

Much of the city’s permit and licensing activity is documented on L&I’s eCLIPSE virtual portal, but information for imminently dangerous properties is kept on an internal spreadsheet, the controller’s office found.

Brady said she has been told that updating the online system would be costly because the city is required to pay an outside vendor to change the site.

If L&I determines that a property could collapse or endanger others, the department can acquire a demolition permit through a court process. The owner has a chance to appeal, potentially delaying the demolition for 90 days.

In the meantime, inspectors are required to check on the site every 10 days for a possible emergency, further straining the department’s limited resources, the controller’s office found.

The report recommends that L&I set up an active recruitment campaign for inspectors; implement a payment collection process to recover additional demolition costs; begin tracking dangerous properties through eCLIPSE; work with the courts to reduce delays in processing permits; and provide support to inspectors conducting follow-up visits.

“This is not about pointing fingers,” Brady said. “This is about working together to find solutions.”

Basil Merenda, L&I commissioner for inspections, safety and compliance, said Mayor Cherelle Parker has directed his division to study the controller’s report and implement the recommendations to the best of their ability.

“Our mandate from the mayor is a safer city, in which dangerous and imminently dangerous buildings are closely scrutinized, and all appropriate actions are taken to safeguard the public,” Merenda said in a statement Wednesday.

Merenda said the findings supplement the L&I Reform Task Force, which submitted a detailed report late last year. Formerly labor director for Mayor Jim Kennery, Merenda chaired the task force and said the administration has been working to implement the plan.

Among the recommendations that arose from that effort was splitting up L&I. Parker adopted that proposal in April, signing an executive order dividing the department into a division focusing on quality of life and another on inspections, safety and compliance.