By Robin Respaut

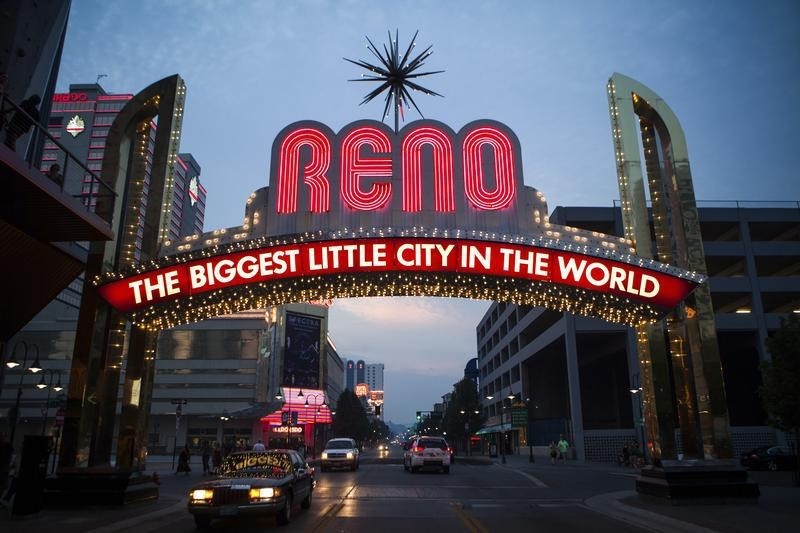

RENO, Nevada – (Reuters) – Mike Kazmierski stood at the podium with good news to report to the 400 local businesspeople who had gathered to hear him speak at Reno’s Atlantis Casino ballroom in January. During 2014, 34 companies had relocated to the area. Nearly 4,200 jobs were created, bringing unemployment down to 6.4 percent, a big drop from 2011’s high of 14.2 percent. And in the view of Kazmierski, president of the Economic Development Authority of Western Nevada (EDAWN), the impressive numbers were “just the start.”

Once known primarily for its casinos and quickie divorces, the Reno area has made impressive strides in its attempt to transform itself into a technology hub in the high-desert of Nevada. In the last few years, it has attracted big Silicon Valley names, including Tesla, Apple, and Amazon. But now a new challenge has arisen for Reno: managing its success. Even as the region celebrates its economic wins, it is struggling to cope with the additional demands that the new businesses — and the new residents they draw — will place on Reno’s infrastructure, schools, and city services. “Our revenues lag the demand,” said Robert Chisel, Reno’s finance director. As newcomers are drawn to the area, he noted, “I need to provide fire services, police services, parks services.” Part of the problem, observers say, is Nevada’s tax structure. The state doesn’t tax corporate or personal income, instead relying primarily on sales, property, gaming and mining taxes. That tax system – along with millions of dollars in additional tax incentives – was helpful in luring new companies. But the system has also left the region with few resources to cope with the influx of new businesses and residents. “The tax structure isn’t based on the economy of the future. It’s based on the economy of the past,” said Stephen Brown, economics professor at University of Nevada, Las Vegas. “If Reno is going to become another Silicon Valley, then it’s going need a tax structure that keeps up with providing services for that type of economy. It’s not going to be gaming and mining.” CHALLENGING TIMES

Reno’s play to attract high-tech business grew out of desperation. Just four years ago in 2011, the city was on the state’s watch list for potential insolvency following a rapid revenue decline. Hit hard by the recession, Reno lost 30,000 construction jobs, and the city had to cut 500 positions, a third of its workforce. Home prices tumbled by 58 percent, and gambling revenues fell dramatically across the state. One of the first successes came in 2012, when Apple announced it would invest $400 million to build a data center. Soon after, tech companies Zulily and eBay and retailers Urban Outfitters and Petco [PETC.UL] followed. Amazon relocated a distribution center to the area. Then, in September 2014, came the region’s biggest score: Tesla Motors announced it would open a battery manufacturing plant in the area, eventually creating 6,500 jobs. But attracting the companies wasn’t cheap. Since 2011, the state has agreed to $1.4 billion in tax abatements for 38 companies within a 25 mile radius of Reno. In two of the largest deals, Nevada gave Apple a tax break over 10 years that will save the company some $55 million in taxes – this in exchange for the promise from Apple of 35 jobs paying an average $25 per hour. For Tesla, the state agreed to forgive 40 percent of the company’s taxes for 20 years, a gift expected to ultimately cost the state $1.3 billion in lost revenues. But Nevada estimates the company will directly and indirectly spur 22,500 additional jobs and $955 million in annual income for local businesses. “I think at some point, the state of Nevada is going to have to look at how it is going to pay for services,” Brown said. “When you bring in businesses that are big, you generate jobs, but if you then exempt them from taxes, all those people who came with the company are going to demand schools for their children and police for their neighborhoods.” STRUGGLING SCHOOLS

In Reno’s Washoe County, the school district is already at a breaking point. Over-capacity and utilizing 228 temporary portable classrooms, the district added 562 kids last year – enough to fill an additional elementary school. If, as conservative estimates suggest, 30,000 new residents were to move to the Reno area over the next five years, the district would need five more elementary schools, three middle schools, and 1.5 high schools. “Right now, we have severe funding issues,” said Pete Etchart, the district’s chief operating officer. “If we don’t find relief, we’re going to go to some uncomfortable solutions.” Options under consideration are year-round schools, or double high school sessions – one early morning, another late afternoon. The district says that it has no money for building and is able to make only emergency repairs to its existing schools. A property value cap limits the district’s annual bonding capacity to $20 million, far short of what it would take to embark on a building campaign. The wear and tear is noticeable, said Andrea Hughs-Baird, a 20-year Reno resident and mother of three. She says her children’s schools have fraying carpets, broken sinks and aging heating systems. “The needs are real,” said Hughs-Baird, who co-founded a parent group called, Parent Leaders for Education. “If we were a business, we would never let our schools get into these conditions. We are in dire need.” In January, Governor Brian Sandoval highlighted Nevada as the second-fastest growing state in the nation but said it also had the lowest preschool attendance and high school graduation rates. Almost one of four children lives in poverty. There are signs that the state’s education failings are hindering its attempts to attract new business. When the Las Vegas Global Economic Alliance polled companies that had decided against relocating, the most common reason, cited by 35 percent of respondents, was concern about the quality of workforce education. Infrastructure is another issue, starting with the sewer system. Last fall, Reno and neighboring Sparks were fined for dumping too much nitrogen-rich discharge into the Truckee River, a problem they say they have fixed. The cities are now investing $25 million in sewer upgrades. Money for infrastructure and other needs isn’t easy to find, however. Reno is currently facinga $226 million unfunded liability for retiree health benefits, a $40 million workers compensation liability, and $534 million in long-term debt. But city boosters like Kazmierski think investing in Reno makes sense. “We need to make some changes,” he said. “If we want to depend on gaming, that’s ok. But if we want science, technology, and engineering, we need to put more in the process. I think we have a community that wants to do that.” (Editing by Sue Horton)