Iliyaas Muhammad is part of a small team in the city’s Department of Licenses and Inspections that goes around cleaning and sealing vacant buildings.

It’s an important job, he said, because abandoned properties can be a nuisance for neighbors and a haven for illegal drugs and prostitution.

“You should see the neighbors coming out clapping,” Muhammad said. “The people are very happy, all over the city.”

Now, with hundreds of municipal employees facing potential layoffs, Muhammad is worried he or his coworkers could soon be out of a job, allowing for the deterioration of more abandoned buildings.

“It has a lot of city workers on edge, I know that,” said Muhammad, who has worked for L&I for four years.

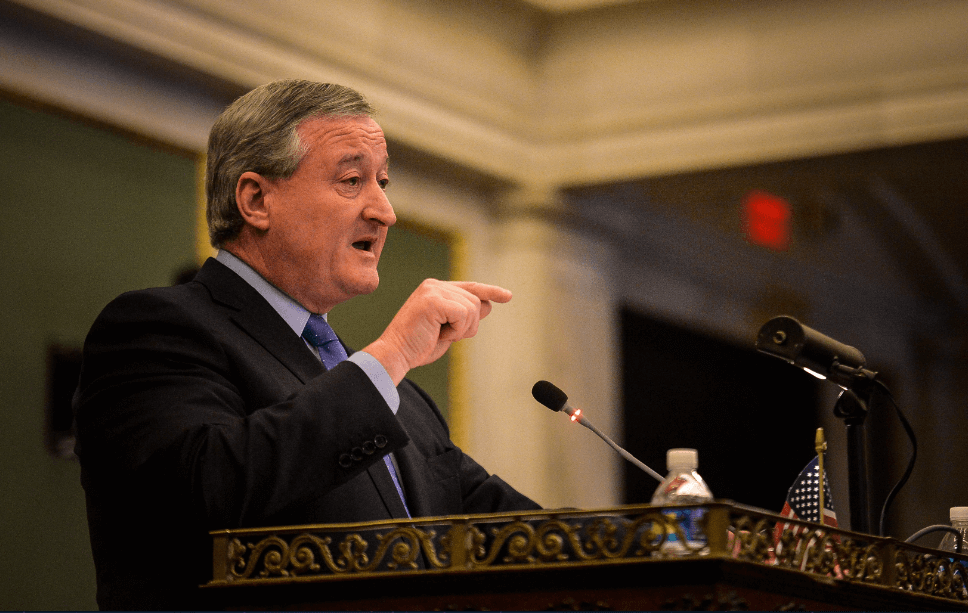

Mayor Jim Kenney’s revised budget proposal calls for mass layoffs, pay cuts, tax increases and other measures to clog up a $650 million budget hole caused mainly by a drop in tax revenue, a result of the restrictions placed on business activity in the wake of the coronavirus.

Kenney’s original proposed budget, which he delivered to City Council in March, had to be slashed by $341 million. The COVID-19 deficit is five times greater than the one the city faced during the 2008 recession, officials said.

Whole departments, including the Office of Workforce Development and the Office of Arts, Culture and the Creative Economy, are slated to be shut down.

Projects, including the building of a new health center and a Philadelphia Fire Department logistics hub, have been put on hold. An initiative to expand street sweeping citywide is no longer in the cards.

City pools will not open this summer, partly because of health concerns but also in an effort to save money.

An ambitious scholarship program aiming to send Philadelphia students to community college tuition-free has been cut in half and will begin at a later date.

In addition, non-union city employees who make more than $35,000 a year will receive pay cuts between 1 and 7 percent, depending on their income.

However, for the families of thousands of city workers, the biggest concern is whether they will still be employed. The first round of layoffs will occur June 1, with more expected to follow.

Officials have said it’s not yet been determined exactly how many employees will be left jobless, and they have not disclosed which departments will be most affected, though Kenney assured no police officers or firefighters would be axed.

“This is a pandemic,” said Peter Cutty, a member of District Council 33 Local 1510, a union representing employees at the city-run airport. “Nobody should be out of a job right now.”

Kenney called the layoffs and pay cuts the “most painful part” of revising the budget, though he defended his administration’s proposal and said he approached the process with safety, education and health as the top priorities.

“We’ve really attacked this problem in a really serious, thoughtful way to deal with all the issues we need to deal with at the same time removing a $650 million deficit,” he said Friday. “We did a pretty deep dive.”

In rewriting the budget, city leaders were conscious of not wanting to impose a steep increase in taxes, with many residents unemployed and struggling. Only $50 million of the budget gap is being covered by increased taxes and fees.

Business taxes and the wage tax for city residents, which were expected to drop, would be frozen at current rates. Wage taxes on commuters would be increased, and parking taxes and a fee for commercial trash removal would also be bumped up.

Property taxes would be hiked 3.95 percent to help provide funding to the School District of Philadelphia. Homeowners whose properties are assessed at $150,000 would pay about $60 more a year.

The city’s contribution to the school district will increase by $30 million compared to last year. Kenney’s original plan called for a $45 million boost to the school system.

All libraries and recreation centers would remain open under the plan, but hours and programming will be reduced, officials said.

Philadelphia has received $276 million in federal funding to reimburse COVID-19-related costs, though the money cannot be used to make up for lost revenue and has to be spent by December.

City Finance Director Rob Dubow said additional aid from Washington, especially to cover lost taxes, would be “an enormous help.”

Abbe Klebanoff, a member of District Council 47, which represents white-collar municipal employees, is hoping for more federal funding, too. She’s worried seasonal workers, who play a big role in her department, will be among the first to be cut.

“They’re some of our most dedicated workers that go above and beyond. They count on this money to live,” she said. “Without them, we’re not going to be able to function that well. I don’t even know what it’s going to look like whenever we go back.”

Klebanoff, who didn’t want her workplace published, is part of a group of progressive city workers who have put together a petition calling on Kenney and city leaders to enact other measures, like higher taxes on big businesses, to close the deficit.

Other demands include ending the tax abatement for new construction and instituting a payment-in-lieu-of-taxes program for large educational and cultural institutions.

“There’s no reason why they can’t raise taxes on the 1 percent and people that are doing just fine in the pandemic to make up for the shortfall that they have,” said Cutty, who is also involved in the effort.

Kenney’s proposed budget package has been sent to City Council, which will hold a series of hearings on the plan. The city must pass a budget by June 30.