A panel of state judges on Wednesday heard arguments from teams of attorneys over whether Philadelphia and other cities in Pennsylvania should be able to implement their own gun control laws.

Firearm preemption statutes, on the books since the 1970s, prevent municipalities from enacting such ordinances, leaving the power to regulate guns solely in the hands of legislators in Harrisburg.

Lawyers representing the city, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh residents affected by shootings, and CeaseFirePA, a statewide anti-violence group, are seeking to have the preemption laws deemed unconstitutional.

Their argument is that the enactment and expansion of the statutes has put people, particularly Black and brown residents of poor neighborhoods, at higher risk of being a victim of gun violence, thus potentially robbing them of their life and liberty.

Preemption has been repeatedly upheld in the courts and there’s no definitive relationship between the laws and increased rates of violence, attorneys for the state and legislature said.

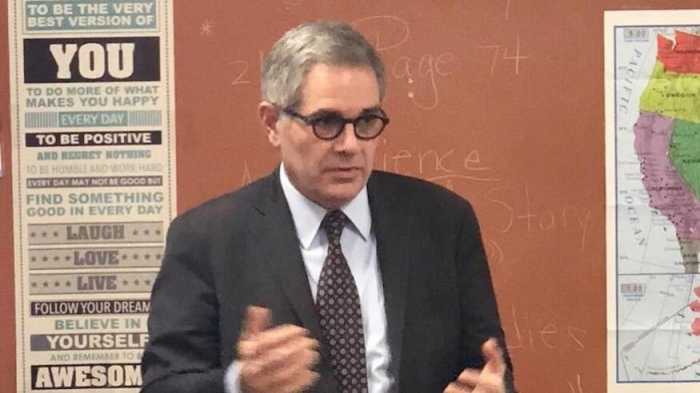

“The legislature is the proper place for complicated issues of social welfare to be debated and contested, and that happened, and this law was passed,” said Tom Collins, representing the General Assembly, during Wednesday’s oral arguments.

“We believe that there are grave policy implications if the General Assembly and its leadership can be sued for failing to enact legislation that certain groups favor,” said Mark Bradshaw, counsel for House Majority Leader Bryan Cutler.

Commonwealth Court Judge Patricia McCullough seemed to agree, pointing to cases upholding the legislative hierarchy.

“So how do you have a legally cognizable claim in light of those, and why aren’t you going to the General Assembly to lobby for a change in the law?” she said. “It sounds like that’s what you want.”

During the hearing, the panel of judges appeared more skeptical of the city’s argument, directing no questions toward the lawyers for the state and legislature.

“What you’re asking for is for each county to be able to have its own firearm owner and use ordinance,” McCullough said.

Both sides will await a ruling, which will likely come over the next couple of weeks.

Pennsylvania’s firearm preemption rules have been targeted, unsuccessfully, by city leaders in the past.

In the mid-1990s, legislation regulating assault rifles was overturned; and the state Supreme Court affirmed a ruling against a slate of city-backed gun control measures in 2009.

Attorney Alex Bowerman, who’s representing the city and other petitioners, said previous attempts to take down the statutes did not make the same constitutional arguments.

“There’s never been a challenge like this to the firearm preemption laws,” he told the judges.

Bowerman said the inability of Philadelphia and Allegheny County to pass their own gun regulations strips freedom away from residents and has a disproportionate impact on a subgroup of the population.

Black Pennsylvanians are 19 times more likely to be killed by gunfire, and residents of the city’s poorest neighborhoods are 25 times more likely to be the victim of a fatal shooting compared to those living in wealthier areas, according to Bowman.

With a favorable decision, city officials could approve stricture gun restrictions, which they believe could help get a hold on Philadelphia’s gun violence crisis.

Mayor Jim Kenney and other leaders announced the lawsuit in October at a news conference. He has blamed Pennsylvania’s lax gun regulations on the city’s soaring homicide rate — 233 people killed so far this year, up 33%.

If not for preemption, measures previously supported by City Council, including a one-gun-a-month limit and requiring gun buyers to get a permit before their purchase, could move forward.