Homeless outreach workers walked the perimeter of the encampment on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway Wednesday morning, a day after a federal judge ruled that the city can move forward in clearing it and two other camps.

Lamar Harold, who has been homeless for about 18 months, said he feels better and safer staying at the camp compared to the shelters, where he said conditions are deplorable. He has no plans to uproot.

“I’d rather be in prison than be in a shelter,” Harold told Metro.

Federal District Judge Eduardo Robreno, in an opinion issued Tuesday afternoon, said Mayor Jim Kenney’s administration “is permitted but not required” to dissolve the encampments, provided there is at least three days’ notice and the city stores the belongings of camp residents.

Kenney, in a statement, said city leaders are evaluating their options and have not arrived at a firm timeline on when to issue the court-ordered 72-hour notice. It would be the third time officials have ordered the camps to be vacated.

“We maintain the position that the camps cannot continue indefinitely,” the mayor said. “I urge those still in the camps to voluntarily decamp and avail themselves of the beneficial services being offered.”

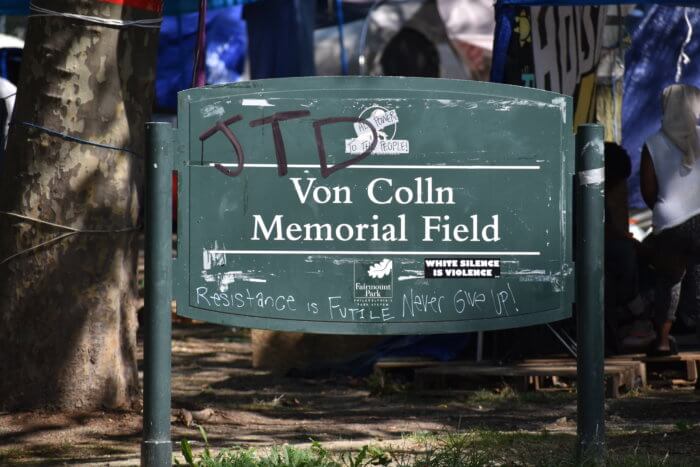

A combined 230 people live at the encampments on the Parkway, at Jefferson Street and Ridge Avenue near the Philadelphia Housing Authority’s headquarters and at Azalea Garden outside the art museum, according to organizers.

Activist Jennifer Bennetch, one of the camp leaders, said she has talked to those living in the tents, and they are not eager to leave.

“Despite this ruling, we are still in active negotiations with the city,” she said. “We are still communicating and having meetings with city officials trying to come to a resolution.”

Robreno’s ruling was on a motion filed on behalf of camp residents to block city action to clear the encampments.

They argued that it would violate their First Amendment rights, since the encampments were founded partially as a protest for affordable housing in the wake of massive Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

In addition, the motion claimed removing the camps would infringe on their property rights, as advocates don’t believe officials’ promises to safeguard items at a warehouse for 30 days.

Kenney has argued that the encampments have been posing growing health and safety risks. Neighbors have filed hundreds of complaints about the camps.

Robreno wrote in his opinion that there’s no indication that the camps, which appeared in June, would be removed with the intent of limiting freedom of speech.

He also said property rights wouldn’t be violated as long as the city follows its procedure to store belongings; however, Robreno did recommend that the Kenney administration adopt a formal written policy about holding personal items from a dissolved encampment.

Last week, city workers gave encampment residents about 24 hours notice to close the three camps after talks broke down between the Kenney administration and camp organizers.

Kenney criticized advocates’ shifting list of demands, and officials said the city offered to potentially set up a sanctioned encampment, build a “tiny house village” and work with organizers to set up a land trust.

Bennetch said municipal negotiators never met the group’s principal demand, permanent housing for all living in the camps.

“They haven’t offered housing for anybody,” she said.

Kenney said the city has offered all camp residents individualized pathways to long-term housing and placed more than 100 in emergency shelters, temporary housing and COVID-19 quarantine space.

All sides seem to agree there needs to be better approaches to handling homelessness.

“The task of finding if not a solution at least some relief to this crisis rests squarely on the shoulders of the city’s elected officials,” Robreno wrote in his ruling. “It is an enormous challenge. But further indecision and neglect will only make it worse.”