On March 16, 2020, all non-essential businesses in Philadelphia were abruptly told to close in an attempt to prevent an outbreak of a serious new virus.

The first coronavirus case had been confirmed six days prior, and, at the time, only nine infections had been detected.

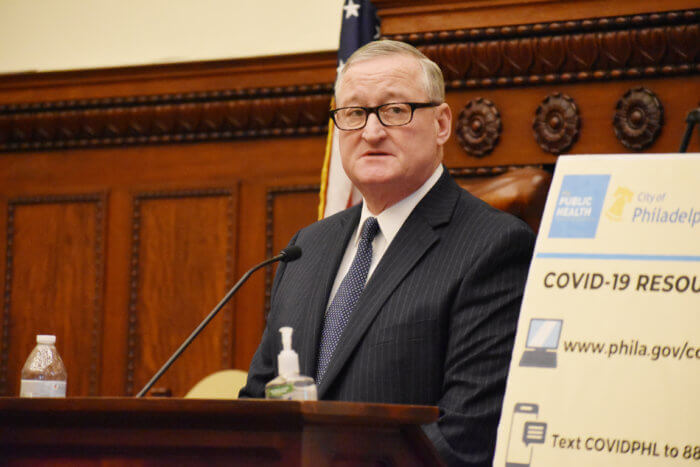

Mayor Jim Kenney, in announcing the shutdown, acknowledged that “these changes will disrupt life in Philadelphia” and said he was aware of “the potential devastating effect” it would have on workers and businesses.

In the two years since, 4,909 Philadelphians have died of COVID-19, and the city’s health department has tallied more than 306,000 positive tests.

Now, as the city enters the pandemic’s third year, more than 1 million residents are fully vaccinated, and nearly all restrictions related to the virus have been lifted.

Health department data shows Philadelphia is averaging fewer than 50 cases a day, and less than 1% of COVID-19 test results are coming back positive. Both numbers are nearing two-year lows.

Just last week, the School District of Philadelphia and other city schools went mask-optional for the first time, and, earlier this month, Kenney’s administration dropped its indoor mask mandate.

Masks — perhaps the pandemic’s enduring symbol — are only required in a few settings, such as on public transportation and in health care facilities.

On Monday, Philadelphia’s criminal court system expanded its number of weekly jury trials, doubling from four to eight — one of many examples of how life in the Delaware Valley is ramping up again.

Still, the city’s economic recovery, by some measurements, has been slow, particularly compared to the suburbs and nearby cities.

Philadelphia has 7.6% fewer jobs than in 2019, before COVID-19 arrived, and the employment loss has had a disproportionate impact on Black, female and low-income workers, according to an analysis released last month by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

The report projects that 14% to 27% of the people who worked in-person in Philadelphia prior to the pandemic would continue staying home full-time or at least part of the time, equating to 11,300 to 18,900 fewer employees in the city each day.

Restaurants and others in the hospitality business have been among the hardest hit; in some cases, their businesses were the first to shut down and the last to fully reopen. The financial situation for many eateries in the city is “still very dire,” commented Ben Fileccia, senior director of operations for the Pennsylvania Restaurant & Lodging Association.

“Just because all the mitigation is over, just because restaurants are back open, just because everybody’s at full capacity does not make up for probably about 18 months of restricted revenue, including months of almost zero revenue,” he said.

New challenges have emerged, such as labor shortages and the rising cost of food. For other restaurateurs, bills that have been piling up can no longer be ignored.

“These next three or four years ahead of us, we’re gonna lose a lot more restaurants due to the issues that happened in 2020 and 2021,” Fileccia added.

He conceded that there have also been silver linings. In Center City and other neighborhoods, streeteries and sidewalk cafes are likely permanent; and food service workers as a whole have earned better pay and benefits.

The organization behind the Pennsylvania Convention Center recently said that it plans to host 150-plus conferences and other events this year, which officials project will result in 450,000 visitors and a $371 million economic impact.

A sector that seems poised to continue growing over the next few years in Philadelphia is life sciences, particularly gene and cell therapy.

In 2021, a total of $12 billion was invested in the life sciences locally, said Claire Greenwood, executive director and senior vice president of economic competitiveness at the Chamber of Commerce for Greater Philadelphia.

“The real estate community is also putting some extra emphasis in the life sciences space because it’s an industry where at least part of the business needs to be done in-person,” added Greenwood, who has led the chamber’s recovery initiative.

From University City to the Navy Yard, labs and other facilities are being built, and former office spaces in Center City are also being retrofitted.

Drexel and Gattuso Development Partners on Tuesday revealed plans for an 11-story life sciences building near the 32nd Street Armory. The development, described as the largest of its kind in Philadelphia, is expected to open in 2024.

That may seem like a long time from now, but it’s only two years away.

Metro is one of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on economic mobility. Read more at brokeinphilly.org or follow on Twitter at @BrokeInPhilly.