Water leaks, flickering lights and a broken bathtub, among other issues, have created a hazardous situation at Rasheeda Turner’s house, and her landlord and city inspectors, she said, have done little to remedy the problems.

“I’m worried about having an electrical fire. It is going to take me to lose one of my kids or myself until you decide to do something,” said Turner, a mother of three young children, including an infant. “I feel like we’re being treated like animals, like dogs.”

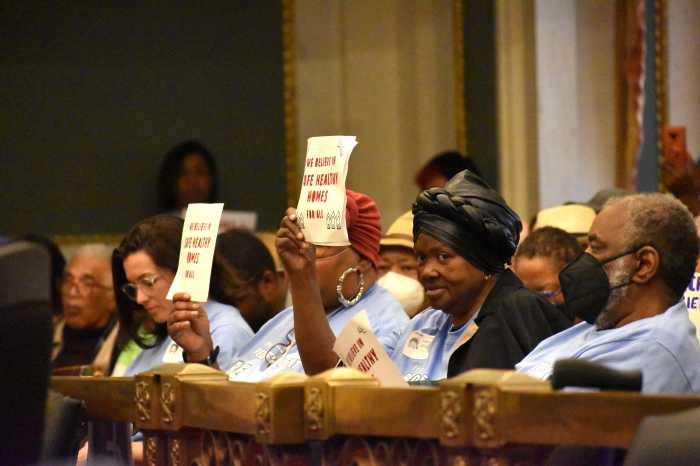

Turner, a member of Philly Thrive, testified Tuesday in front of City Council, as part of a series of hearings on the municipal budget and Mayor Cherelle Parker’s proposal to borrow $800 million for her housing plan.

She was joined by representatives from the Philadelphia Coalition for Affordable Communities and other groups advocating for additional city resources to be devoted to home repair and rental inspections, along with a host of other residents commenting on a myriad of budget-related topics.

Angelita Ellison recounted being forced to move out of a house her grandparents had purchased in South Philadelphia when her mother could not afford repairs and was turned away from the popular Basic Systems Repair Program.

Since then, she and her sister have moved from Northeast Philadelphia to Frankford to the Girard College area, in search of a place they can afford.

“Most of the changes in this city that I’ve seen do not benefit the people who have always lived here,” Ellison told lawmakers. “Now Mayor Parker is proposing more changes. I am here today to ask the City Council to pass a budget that benefits those of us who need housing resources the most.”

A few others who testified Tuesday morning spoke about their experiences in substandard housing, going periods without heat and hot water and facing water damage and structural issues.

“This budget needs to be about us, not the big landlords and the developers,” Debbie Robinson, of Philly Thrive, said. “Imagine that your family is going through this right now. How would you feel?”

Perhaps Parker’s most ambitious proposal since taking office, the Housing Opportunities Made Easy, or H.O.M.E., initiative aims to create or preserve 30,000 units of affordable housing in four years through investments in more than 50 new and existing programs.

Aside from the $800 million in bonds, the plan would utilize $1 billion worth of city-owned land and $200 million from a mix of sources, according to the administration.

At a hearing on the H.O.M.E. initiative a week ago, Council members pressed Parker’s team to justify expanding income qualifications for some widely-used benefits. Similar concerns were raised at an initial all-day session on the plan April 23.

Lawmakers have, in particular, questioned the wisdom of raising the eligibility for BSRP, which already has a hefty waiting list, from 60% of area median income ($74,800 a year for a family of three) to 100% AMI ($107,500).

BSRP provides emergency electrical, plumbing, roofing and other repairs at no cost, and the Parker administration has argued that income restrictions have excluded those who make just over the limitations.

“The argument has always been, if a person makes a little bit more,” Council President Kenyatta Johnson said during the May 7 hearing. “What is a little bit more? Is it $5,000, $10,000, $20,000, $30,000?”

“The difference is a person who has to make a decision between getting their roof fixed or paying their mortgage,” he added. “But then you may have another person who may be, ‘I can get the roof fixed, I can go to Cancun and then still apply for this program to get my roof fixed.’”

AMI is calculated on a regional level, accounting for people who live in the nearby suburbs, New Jersey, Delaware and even a section of Maryland. Households within city limits average out just below 60% of AMI, according to municipal officials.

In addition to BSRP, Parker’s plan calls for increasing eligibility for the Adaptive Modifications Program, which funds free accessibility projects for people with disabilities, to 80% AMI, up from 60%.

Councilmember Jamie Gauthier, chair of the body’s housing committee, said last week that she received information indicating that less than 10% of the thousands of people turned away from the programs in 2024 made too much money to qualify.

Raising the income limits — thereby increasing demand — without a significant influx in funding and support staff “runs the risk of paralyzing” BSRP, Gauthier said. Those worries were echoed by several of the housing activists who testified Tuesday.

Parker says “that we shouldn’t have to choose between the have-nots and people who have a little,” Mitch Chanin, of Philly Thrive, told lawmakers. “Residents whose incomes are above the threshold absolutely need and deserve support, but we do have to choose right now because the total budget for home repairs is way too small.”

Jessie Lawrence, director of the city’s Department of Housing and Development, said at the May 7 hearing that “we don’t think that looking at income alone really quantifies the actual need.” Parker’s chief of staff, Tiffany Thurman, noted that some residents with higher earnings may be impacted by health care costs and student loan debt.

Legislation authorizing the H.O.M.E. initiative borrowing is expected to be formally introduced in Council on Thursday. The Parker administration is pushing to have the plan advance alongside the yearly budget, which must be adopted by July 1.

“We’re going to work it out,” Johnson said last week. “And then we’ll come up with a compromise that we all can agree on and make sure we’re supporting those most vulnerable.”