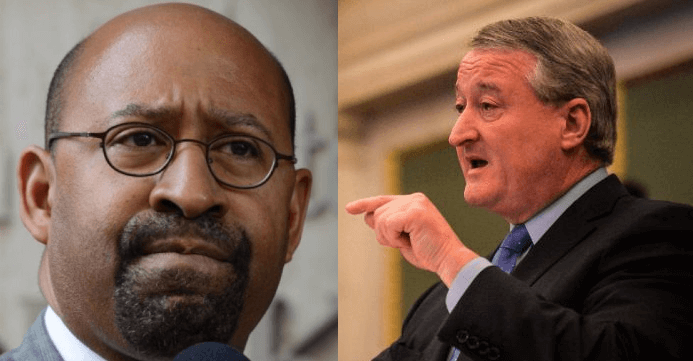

Philadelphia Health Commissioner Thomas Farley resigned Thursday, at the request of Mayor Jim Kenney, following revelations about his handling of human remains recovered from the 1985 MOVE bombing.

Farley, the face of the city’s coronavirus response, admitted that he had the remains cremated and disposed of in 2017 after learning of their existence from officials in the Medical Examiner’s Office, according to a statement issued by Kenney Thursday afternoon.

“This action lacked empathy for the victims, their family, and the deep pain that the MOVE bombing has brought to our city for nearly four decades,” Kenney said. “As a result, I have asked Dr. Farley to resign, effective immediately.”

Kenney called the chain of events “very disturbing” and “disgraceful.” Sam Gulino, the city’s medical examiner, was also placed on administrative leave.

The mayor said he explained the situation to the MOVE family in a private meeting where he also “promised them full transparency into the outside review of this incident, as well as the handling — or mishandling — of all remains of every MOVE victim.”

City Managing Director Tumar Alexander described the remains as “bone fragments,” though officials said it is unclear whom they belonged to and how many people’s remains were cremated. Kenney and Alexander also told reporters they do not know what was done with the ashes.

“My understanding is — this is a policy that we’re going to change — that this is not uncommon for remains to be disposed of in this manner, and it’s wrong,” Kenney said.

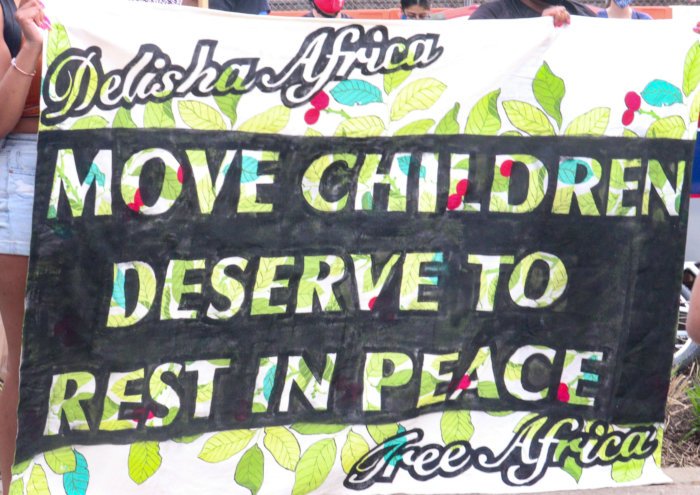

Farley’s departure comes in light of a broader reckoning over the MOVE bombing’s legacy and the treatment of those who were killed.

Eleven people, including five children, died after police dropped explosives on a West Philadelphia house during an armed standoff with the group.

Thursday marked the 36th anniversary of the bombing and an evening commemoration was planned near the site on Osage Avenue.

Last month, there was an outcry after it was learned that the remains of a girl killed in the bombing had been kept by academics at the University of Pennsylvania and Princeton University and used in courses.

The colleges’ role in the situation came to light after the Inquirer published a piece by activist activist Abdul-Aliy Muhammad.

Penn leaders later issued an apology and said they hired attorneys to investigate how and why the remains were kept at the university’s museum for the better part of four decades.

Kenney said his office has also hired a law firm to conduct a probe and produce a report on what transpired.

“It is imperative to understand the knowledge and actions of others in my administration at the time,” he said in a statement.

Kenney said he learned of the situation Tuesday at 5 p.m. after Farley disclosed his actions to top administration officials. The findings were made public Thursday at the request of the MOVE family, according to the mayor.

Farley, as health commissioner, led Philadelphia’s COVID-19 response, and, as recently as this week, Kenney lauded his work.

“Because of his leadership and knowledge, we were able to balance the desire to reopen as quickly as possible with the need to keep people healthy and prevent deaths,” the mayor said Tuesday, in announcing the city’s decision to remove pandemic restrictions next month.

However, Farley’s tenure was not without controversy. He faced calls to resign after the city worked with Philly Fighting COVID, a now-disgraced group that operated Philadelphia’s first mass vaccination clinic.

Farley and other health department leaders were faulted for not vetting the organization, which quietly shifted to a for-profit company, adopted questionable privacy policies and misused vaccine doses.

Dr. Cheryl Bettigole, who previously served as director of the health department’s division of chronic disease prevention, was appointed acting health commissioner. Kenney said his office will undertake a nationwide search for a permanent replacement.