Although he grew up under the infamous Duvalier family dictatorship, known for two generations of systematic human rights violations, Josephys Dafils recalled the Haiti of his youth as safe. Before 1986, the small Caribbean nation which shares an island with the Dominican Republic had a growing tourism industry, a local currency with buying power, and native people with a “live and let live” attitude. According to Dafils, his mother and father kept their heads down, worked hard, and made a modest life for themselves.

Twenty-five years ago, Dafils, who never dreamed of leaving his homeland, moved to the United States, sparked, in part by the 1991 Haitian coup d’état. Now, forced by years of economic hardship, increasing American interference, and rising political turmoil, thousands more Haitians continue to do the same. Every day they make a dangerous, sometimes deadly passage through South America in hopes of reaching the U.S. border.

“They die in the road, they cannot do it, or they’re sick, and you just have to jump over that person that you were talking to two days ago to just go [to the border] and keep going,” Dafils said. “Some of them are raped, some of them they steal their money, they steal the food that they have … They are traumatized and us here who are trying to help, we’re being traumatized by the stories that they are telling us.”

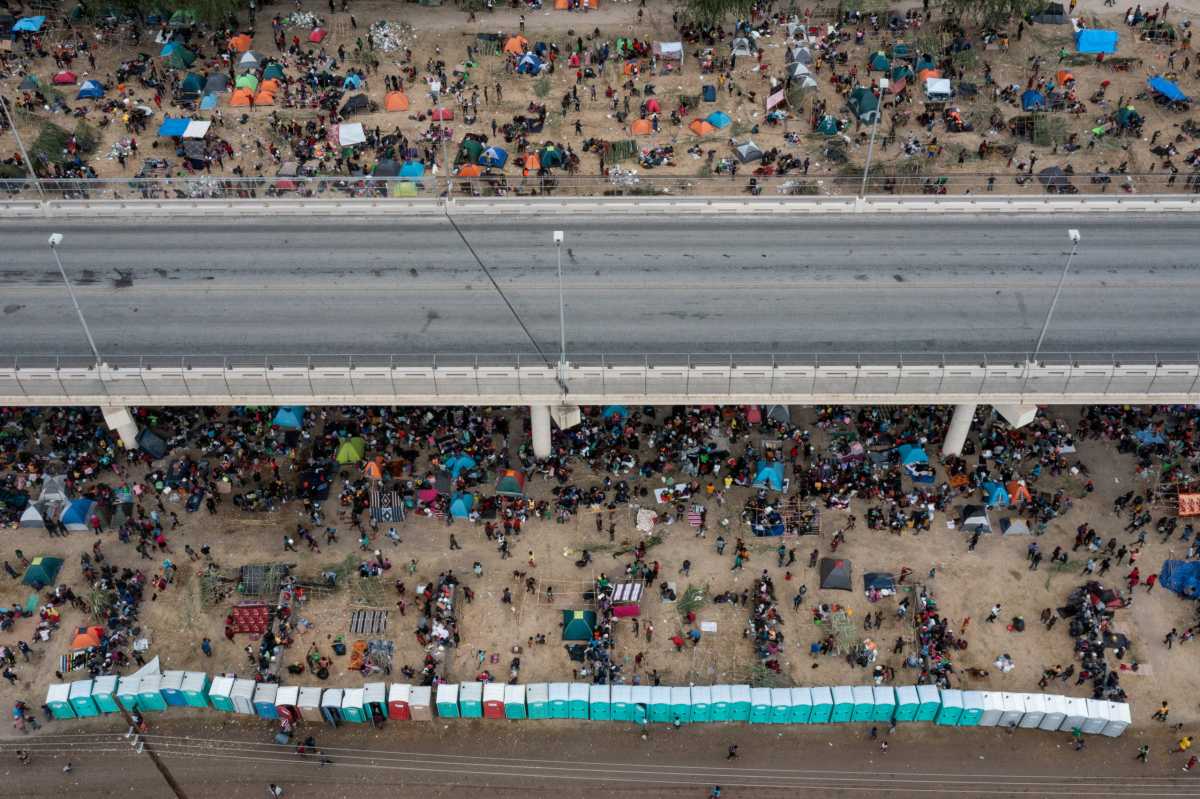

Dafils, a social worker at Philadelphia’s Department of Human Services and the founder of Haitian American United for Change, is among the city’s significant Haitian population angered by the recent humanitarian crisis and inhumane treatment of refugees at the U.S. border in Del Rio, Texas. Throughout the region, first and second-generation Haitian immigrants and their families spent the year dealing with tremendous tragedy back home, including a magnitude 7.2 earthquake that killed over 2,000 people and the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in July. A couple of weeks ago, they looked on in horror with the rest of the world as U.S. Border Patrol Agents violently corralled refugees, taunted them with profanities, and twirled oversized horse reins at them — images that echoed the worst of the country’s racial injustices during slavery.

But Dafils, and others in the city’s Haitian community—such as Jennifer Joseph, deputy director of HIAS PA, a nonprofit that supports low-income immigrants of all backgrounds—are making their voices heard. They represent a new generation of millennials — business owners and professionals — determined to speak up, fundraise, and demonstrate against the status quo.

“I actually feel that many people are not as focused on Haiti right now as they should be,” Joseph, who also sits on the board of Haitian Philadelphia Professionals, said. “I think the country deserves a lot more attention and support than what it’s been getting.”

Joseph was specific in her language, too, calling the images coming in from the border traumatizing. As the daughter of two proud Haitian immigrants and someone who dedicates her life to helping others begin theirs anew in the U.S., the situation overwhelmed her. Over 10,000 Haitian refugees made their way to the Del Rio border through treacherous conditions — with some not making it at all — and slept in squalid conditions under a bridge without food or water. As Texas Gov. Greg Abbott made a makeshift border wall of parked cars, President Biden enacted a Trump administration COVID policy that allowed him to fly thousands of migrants back to Port-au-Prince after detaining them for days.

“I would encourage everyone to acknowledge the fact that Haitians have been historically ignored,” Joseph said. “When you look at immigration in this country, it’s always been more difficult for immigrants who are trying to enter the country from countries of African descent or Caribbean countries.”

“I think it’s important for everyone to look within and say this is an issue — this is an issue that deserves our attention and these are a group of people who have been ignored for decades,” she continued.

The problem continues even here in Philadelphia. While groups like Pew list the city’s Haitian population at 8,800 as of 2016, the number is most likely more considerable and unknowable. According to Dafils, the Census, for example, doesn’t ask if a person is of Haitian descent, leaving most to mark off either Black or African American. Building community and offering assistance becomes difficult without knowing who’s out there.

But Dafils and Joseph, through their respective organizations and others in the community, are doing just that. They’re holding rallies, helping with housing, and assisting the city’s Haitian population with finding their voice, among other things.

“I definitely want Americans to get to know us,” Dafils said. “Get to know our food; get to know our music.”

To learn more about Haitian refugees or to give a donation, visit Haitian American United for Change at haucpa.org or Haitian Philadelphia Professionals at phillyhpp.org/support-us.