Founded in 1824, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP) is not a museum, but something more — the United States’ largest archive of and research library for documents, books, manuscripts and graphic images dating back before the start of this nation.

A key role of the HSP —”the documentation and study of ethnic communities and immigrant experiences” — is central to its latest exhibition, ‘Free as One: Black Worldmaking in the Pennsylvania Abolition.’ Curated in collaboration with the 1838 Black Metropolis — a Philadelphia organization committed to reclaiming, rewriting, and restoring overlooked Black histories — the exhibition explores the legacy of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society (PAS), as it marks its 250th anniversary. ‘Free as One’ runs through May 23.

Instead of perpetuating the outdated and misleading narrative that the PAS’s predominantly Quaker White membership — among them Benjamin Franklin, who petitioned Congress to ban slavery in 1790 — led the abolition movement, ‘Free as One’ makes it clear that self-determined Black men and women were the true architects of their own liberation. These individuals not only fought for their own freedom, but also advocated for Indigenous and other enslaved people, asserting their agency and igniting a global, Black-led political and cultural movement with their banners of freedom held high.

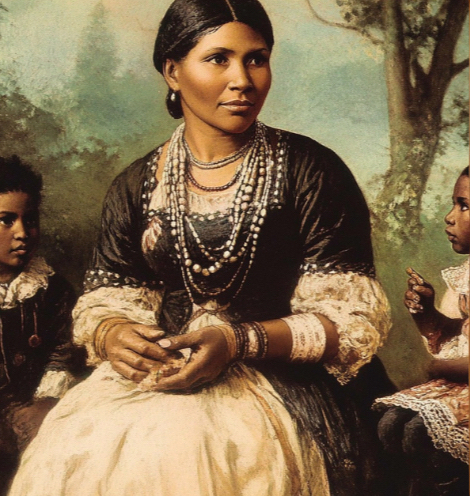

“The ‘Free as One’ exhibit is proof of how and what really occurred,” says Justina Barrett from HSP’s Chief Learning and Engagement Office, waving her hand at the expanse of glass cases, files and AI-generated depictions of Black leaders whose energies fueled the abolition movement.

The centuries-old, yellowed documents in ‘Free as One’ — indenture papers, well-intentioned yet demeaning government-sanctioned qualifiers, and receipts of payment after payment made by Black men to their enslavers to secure freedom—tell a painful story. Many of these records reveal husbands relentlessly working to free their wives or mothers fighting to ensure their children’s liberation. These documents weigh heavily on the heart and soul—a stark reminder that countless individuals were once forced to plead their case and prove their right to freedom.

Morgan Lloyd, co-founder and president of 1838 Black Metropolis, and Michiko Quinones, 1838’s co-founder and Director of Public History and Education are the curators behind ‘Free as One.’ Guided by the work of historians Kristen Sword, Gerald Horne and CLR James, focusing on the archives of PAS and the Leon Gardiner Collection (Gardiner was an Atlantic City postal worker and avid collector of African-American historical documents and cultural ephemera), Quinones encourages one-and-all to view their historical findings, and look to their future.

“People should understand that the archives of PAS and the Gardiner Collection may have their ancestors, but also contain information that has not yet made into history books,” she says. “Maybe they can write that next book. Or create that visualization. Or that song or whatever they are motivated to do to lift the story out of the paper.”

Quinones welcomes the earliest work of Pennsylvania Quakers, stating they long had a movement within their own ranks to end enslavement.

“In fact, when New Jersey was founded as a Quaker colony in the late 1680s with Burlington as the capital, its first constitution forbade slavery,” she adds. “British-led mercantile capitalism came in the early 1700s, and many Quakers merged into that way of thinking, so the early Constitution and the anti-slavery movement had to struggle through these competing forces within the Quakers until 1776. In 1776, the Quakers decided to kick anyone out of meeting who was still involved in enslavement.”

Quinones emphasizes that while the Quakers were still grappling with their own stance, Black people were securing their freedom “by any means necessary” even before the 1770s.

“Black and indigenous people were challenging the laws of the land in court as one of the methods to get free,” she says. “After 1776’s mass manumissions, a free Black community developed here that had spatial stability, a term coined by (historian) Emma Lapsansky-Werner. This was a place where legal framework was different from the rest of the country. You had community here, a place of protection, the beginnings of legal precedents against enslavement, and groups who could assist with that, like the PAS.”

Quinones discusses ‘Free as One’s Black and Indigenous people’s affidavits for their own freedom, the likes of which helped the PAS develop working frameworks and legal precedents that were in alignment with their values.

“By 1800 you had a burgeoning free Black population which provided emotional, physical, social, economic support for thousands of people pouring in from the border states and an alliance of Quakers working the legal system with all the variety of cases these folks bought in.”

Ask why we haven’t heard the story of Black-led self-determined freedom, and Quinones believes that the usual American origin story starts in 1776 “with freedom for mercantile capitalism – think Virginia plantation owners – at odds with imperialist capitalism (think the Royal Africa Company) all of whose wealth was based on enslavement,” she says. “Meanwhile, all of this Black civilization building in allyship with Quaker legal precedent building was happening.”

As for the colorful, stately use of AI in order to create a visual guide to ‘Free as One’, Quinones says, “We use AI solely to visualize historical figures for whom no images exist, ensuring their stories are represented with more than words. Following written descriptions and historical context, we depict them exclusively in oil painting-style portraits in homage to 18th and 19th-century aesthetic protocols. We use AI to visualize the personhood of our historical subjects and to honor their legacy with dignity and respect.”

For more information and tickets, visit hsp.org. Please note, due to the Eagles Super Bowl parade, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania will be closed on Friday, Feb. 14.