An investigation into the city’s relationship with Philly Fighting COVID found that the Philadelphia Department of Public Health provided vaccines to the organization without proper vetting and while ignoring troubling signs.

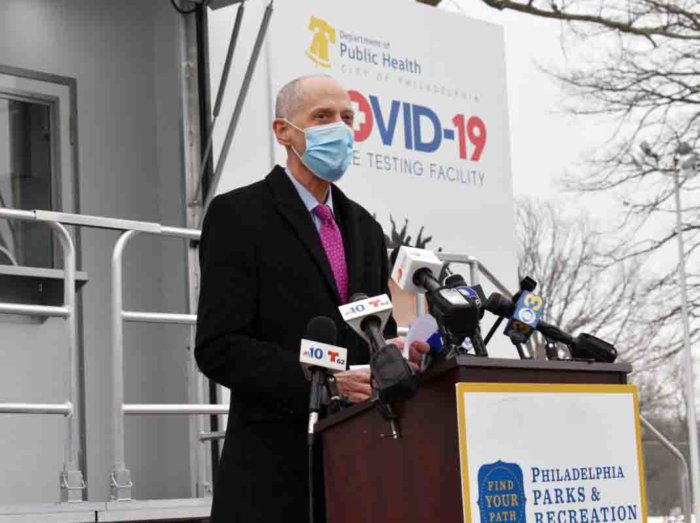

However, the report, released Monday by the city’s Inspector General’s Office, largely spared the department’s leader, Health Commissioner Thomas Farley, who has become the face of Philadelphia’s pandemic response.

PFC, with the health department’s cooperation, ran the city’s first mass vaccination clinics at the Pennsylvania Convention Center.

Officials cut ties with the organization in late January after it was revealed PFC had a questionable privacy policy and had quietly shifted to a for-profit company. Andrei Doroshin, the group’s 22-year-old CEO, also came under fire for taking home vaccines doses.

Farley, for his part, said he has taken on a more active role in vaccine distribution and has expanded the number of people overseeing his department’s inoculation effort.

In July, PFC received a nearly $200,000 city contract to conduct COVID-19 testing, which it later abandoned suddenly to focus on vaccinations.

There were problems from the start of the partnership, according to the IGO’s report, with health department employees describing the relationship as “challenging.”

Doroshin demanded money up-front, unlike other testing providers, and held an unauthorized event in Society Hill, the report said. PFC also provided less demographic information than other city testing partners.

Doroshin did not participate in the investigation based on legal advice, according to Inspector General Alex DeSantis. PFC did not respond to an emailed request for comment Monday.

Early in the roll-out, vaccine distribution was informal and “outside of any structured organization,” investigators found. Deputy Health Commissioner Carolyn Johnson and another top official determined allocation “on the fly,” the report said. Speed and volume were the priority.

Farley, during a press briefing Monday, said the health department was in a hurry and made a bad decision.

PFC was selected to run clinics for unaffiliated healthcare workers at the Convention Center by Johnson. She later resigned after it was discovered she provided information about a city contracting process to Doroshin and the Black Doctor’s COVID-19 Consortium.

By the time of PFC’s first mass vaccination clinics in early January, the health department’s COVID-19 containment team was well aware of the organization’s issues with testing.

But it doesn’t appear that information was shared with the department’s disease control division, which handled vaccine distribution.

“I think a lot of those communication failures happened because the department moved forward without formalizing the relationship,” DeSantis said.

After learning of PFC’s status as a for-profit entity, the organization’s chief medical officer resigned and, days before the mass clinics, he urged the health department to look into PFC and Doroshin, according to the report.

“The health department had that information,” DeSantis said. “They just didn’t think it warranted deeper examination.”

While PFC’s first weekend at the Convention Center went smoothly, cracks began to appear during later clinics, with volunteers who were unqualified to administer the vaccine injecting other volunteers and staffing calling family and friends in for appointments, investigators found.

DeSantis said his team has shared evidence from the investigation with criminal, civil and regulatory authorities. He said the probe will continue, perhaps leading to further ramifications.

The IGO did not recommend discipline for Farley, though the report said he was “disconnected and uninformed” about the PFC situation.

Mayor Jim Kenney, who has stood by Farley, said the commissioner delegated vaccine duties and focused on other areas, such as testing, contact tracing and activity restrictions.

“I wish he was perfect. I wish we all were perfect,” Kenney told reporters. “But I also know that Tom Farley has devoted every waking hour of the past year trying to manage the city’s response to this pandemic as best he can.”

The IGO recommended additional training for all health department employees involved in the contracting process and more transparency around vaccine allocation.

Kenney and Farley said they agree with the conclusions, with the health commissioner calling them “fair and useful.”

After the scandal broke in January, Farley expanded the department’s vaccine team to 20 members, who meet daily and report directly to him. An expanded committee has also been established to review applications submitted to run community inoculation sites.

More scrutiny will be applied to vaccine providers, Farley said, even those, like PFC, that don’t receive any city funding. Officials are considering drawing up a separate agreement for providers to enforce quality standards and equity.

A five-person group that includes Farley is now meeting to decide where doses should be shipped after arriving in Philadelphia.

Kenney noted that the investigation did not find that any municipal employees broke the law or acted out of malice, ill intent or for personal gain.