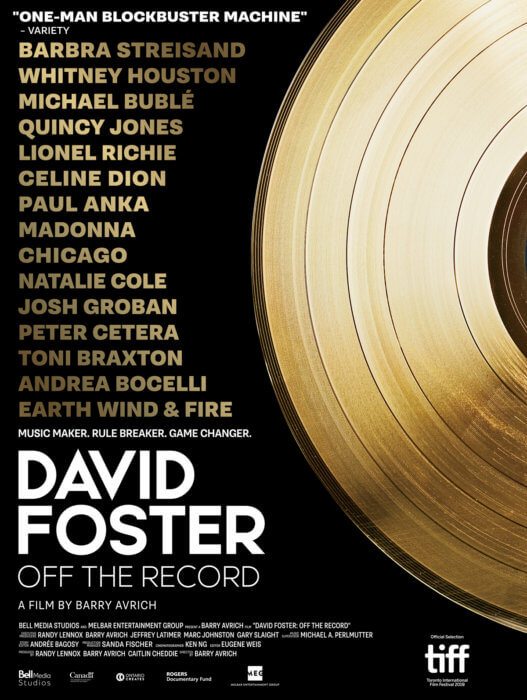

Documentaries can cover a variety of subjects and storylines—really there is no limit to what can be explored. For director Barry Avrich however, he gains inspiration from telling people’s stories, and he does just that with musical legend David Foster in his latest film.

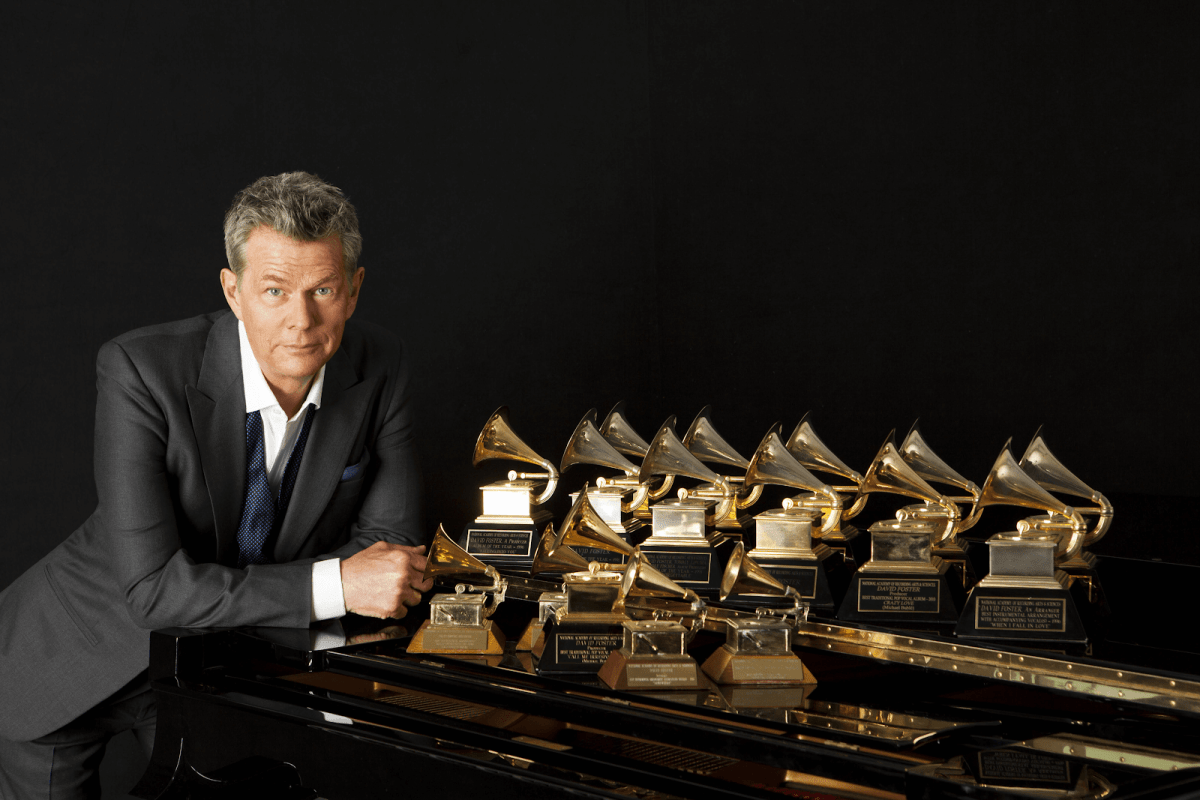

In ‘David Foster: Off The Record,’ Avrich delves deep into the inner workings, musical talents and life of David Foster in a way that people have never seen before. Not only does Avrich get to speak to Foster himself, he also gets to interview people who have worked closely with the note-slinging connoisseur and uncovers a side of Foster that is quite compelling. If Avrich’s goal was to create a pathway into the mind of a musical genius, he certainly achieved that and more by showcasing the human side of someone who most people consider a “legend.”

Avrich sat down with Metro to discuss more on what went into making his latest documentary feature.

When you were approached with this project, what was it that made you want to sign on?

It was a two-layer courtship ultimately put together by a couple of friends after the Quincy Jones documentary was announced and said it was coming to Netflix. But certainly David Foster had a very similar trajectory, and accomplishments and talent in that David Foster would be a great subject for a documentary. I just finished an early documentary called “Prosecuting Evil”—a very serious film and I figured well, it might be nice to switch gears, but I had never met David Foster. I’m very well aware of his music and his accomplishments as an artist, so I went and met him in California, and we began a two-year discussion. We had to be very comfortable with each other. David did not know who I was, I’m sure he probably was hoping for some famous director to make his life’s story and the initial relationship was going to be something that had to be developed. So, for the next two years, we would meet all over the world to sort of discuss the project. I basically set some ground rules of how we were going to make this film together which was that he would not have any editing power, he would not have the final cut, [but] he would get to see it a month before it was released and if there were any substantial errors then I would make those changes. But ultimately he had to be incredibly candid—and he agreed. Whoever said what, whether it was his kids or other people, he was open to it. I remember the first time he saw the film, I showed him the film alone in a dark room and he was very emotional, he admitted that parts of it were very difficult and he was uncomfortable with it, but the first thing he said to me after watching the film was that he knew the rules and he knew that we had a good story.

You’ve said in interviews that you really have gotten access with David Foster that no one else has. Would you say those two years of getting to chat with him was what allowed that access for you?

Well, I’ll tell you there’s no question that he wasn’t going to trust me from the start, even though we developed a chemistry on the first day of shooting, he saw me working with the cameras, he got a sense that I was professional. However, the real breaking point for us was I set up the first interview with him, I did about six, just hours and hours of interviews with him at Capitol Records in LA. I don’t use notes during interviews and he was amazed that we could sit there for hours with eye contact and really get into his life. So, after that interview, he really then began to trust me and give me more access than I thought I would even have. He made everybody available and said to everybody, be honest. So, we developed a chemistry, doesn’t mean we always agreed but that trust developed over time.

You got to interview not only Foster himself but also a variety of other artists that he’s gotten to work with. Were there any interviews that stand out to you in your mind?

Certainly Celine Dion and Michael Bublé. It’s not so much that they owe their career to him because they’re so talented, but the fact that all of these years later [they shared how he had] taken their talent to another level. That kindness and generosity I found really quite inspiring and at the same time surprising because artists are insecure and mostly never want to give credit to others and yet those two really were [open]. There was a wonderful moment where we uncovered some archival footage for the film where he has Celine Dion in the studio for the first time and she belts out a note and he says, ‘That’s fantastic’ and she says ‘Really?’ She couldn’t believe that he was interested. He just knew how to take people to another level. It’s just the thought of [the] dichotomy and tension of taking a group that had been enormously successful and who were looking at the end of their career, and David was able to re-imagine and re-invent [them] even if they’re somewhat uncomfortable with an outsider.

You spent so much time delving into the mind and life of David Foster, what do you feel like you’ve learned about him?

He is a complex man. Canadians tend to be insecure about their success, and I’ve discussed this with everybody from Jim Carrey to Martin Short—we tend to worry about other people thinking that we’ve become too successful, and that’s a Canadian thing, and certainly David has that as well. Also there is the great irony that he writes and produces the greatest love songs in the world but has trouble saying I love you. I really pushed hard in the film to just get to the bottom of that and I challenged him on that and that really came [about] after we were screening the film at the Toronto Film Festival. I really wanted to push hard and get that sense of what made him have a side of him that’s very cold, but he’s [also] so generous and warm. He will give you a hug and he will help you with your career and he does care, but there is a certain Teflon side about him that is quite remarkable. You do see with some other artists where there is insecurity, but David has a tough exterior and he has this extraordinary willingness to help other people.

Overall, what do you hope audiences take away from the film after watching?

You know, I never make films for critics—it’s a losing game to try and appeal to critics. I want to make films that are going to tell people’s stories and be entertaining. What do I hope people get from it? I just want them to sit back and look at a man who is behind the music and who really understands how songs and music are made and remember those songs and enjoy them and understand that [his] talent needs to respected. David Foster needs to be celebrated for the sheer output of what he did and the opportunities he gave to people. David believes that his music will not stand the test of time, and I don’t believe that. When you listen to a Lionel Ritchie or an Earth Wind and Fire or a Whitney, you do remember and love that music and you will forever. One of the most incredible moments for me was when we were in Capitol Records sitting in that studio where Sinatra recorded and I decided to play a couple of his tracks and I asked David to listen to them and remember—he had heard the songs a million times and played them a million times, but alone in that studio, he got lost in this amazing memory and with emotion. It was the most emotional I had seen him. He remembered the phrasing of the songs and how he produced it, what the artists was doing and thinking at the time, and that to me was just wonderful.

‘David Foster: Off The Record’ premieres July 1 on Netflix.