After he got out of jail, George Waters called Joe Budd, his old friend, to see if he would be interested in reconnecting.

Budd and Waters grew up together near the corner of Tulpehocken and Morton streets in Germantown. The pair were part of a crew in the 1970s that sold drugs and caused trouble in the neighborhood.

“I hadn’t seen or talked to George in probably 15, 20 years,” said Budd, who had since moved to Montgomery County, become a deacon and quit drinking.

“He kept saying he wanted to get together just to hang out and talk, and I kept rebuffing him, saying, ‘Nah, I don’t hang out anymore,’” he added. “He kept calling. He was very persistent.”

While serving a five-year sentence for drug trafficking, Waters had begun to think about his old buddies and how, perhaps, they could contribute to the well-being of the place they grew up.

Budd agreed to meet with Waters, and he jumped at the idea. They, along with other members of their old crew, began cleaning up vacant lots.

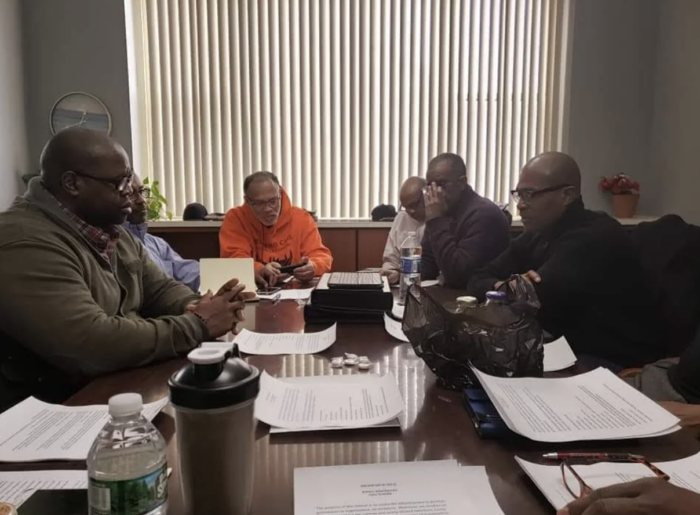

Ten years later, the group, now a nonprofit called Men Who Care of Germantown, runs a food pantry, oversees programs in neighborhood schools and is set to launch an anti-violence program.

They turned a vacant property owned by Budd into a resource center to give students computer access and a safe place to go after school.

In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, the organization expanded on existing relationships with Philabundance and the Share Food Program. Men Who Care serves as an emergency pantry, and it distributes food boxes to between 250 and 300 people every Saturday.

“Right now, we’re like a full-fledged food distribution program,” said Clayton Justice, a Germantown native who joined the nonprofit in 2014 and is now its executive director.

Men Who Care focuses its services on helping vulnerable seniors and children, particularly teenagers who may be feeling the pull of street life.

Food giveaways serve as an opportunity to reach out to another population — parents.

“We’re getting information,” Budd, 63, said. “We’re having conversations with them. We’re engaging them, letting them know what we have planned for when the pandemic lifts.”

On weekdays, Men Who Care hosts an educational pod at Germantown Mennonite Church, where students can complete their virtual classes with supervision and receive breakfast, lunch and a snack.

In the coming months, the nonprofit plans to start a peer-to-peer mentoring program for teenagers through a grant from the city’s Office of Violence of Prevention.

Men Who Care received the funding in October, but, as they were preparing to implement the initiative, COVID-19 shut everything down, Justice said.

Dubbed the Brother’s Partnership, the program will involve four rec center basketball coaches and kids between the ages of 14 and 16. Justice said they will be empowered to make better choices and encourage their friends to do the same.

There will also be conversations about what the youth believe should be done to prevent the high levels of gun violence in Germantown and throughout the city.

“From those conversations, our aim is to create advocacy opportunities to support their ideas,” Justice said.

It’s building on Men Who Care’s “real talk” sessions, where boys in schools are invited to discuss what’s going on in their lives without teachers or staff.

“Violence in Germantown has risen tremendously over the past three years,” Justice said. “We actually know some of the victims. We know their families. Germantown’s a close-knit community.”

Nine people serve on Men Who Care’s board, and the group has 10 to 15 core volunteers. Quite a few no longer live in Germantown, including Waters, who settled in Delaware.

Budd lives in Lansdale and said the volunteers have a special connection to the area.

Men Who Care have been asked to come to schools in North Philadelphia, and they have accepted, but Budd encourages those communities to reach out to neighborhood expats.

“I think that’s what keeps us committed, because we grew up in the neighborhood,” he said.

“It just makes sense that if people from where they grew up go back there and do their community service, community work and send their money there,” Budd added. “Because a lot of people got out, made money and are doing very well.”

For his part, Waters, 61, told Metro he looks forward to the next 10, 20 and 30 years of Men Who Care, and he hopes the organization can establish a legacy in Germantown.

“It’s needed for people to see that men are not just out there dilly-dallying but there are some men in the community that really care about what’s going on,” he said.