More remains from a child killed in the infamous 1985 MOVE bombing were recovered this week at the Penn Museum, representatives from the institution said.

The discovery was made Tuesday, Nov. 12, Penn officials said, while staff were inventorying the facility’s biological anthropology section – an area the museum promised to search after bone fragments belonging to a 14-year-old MOVE victim were found in 2021.

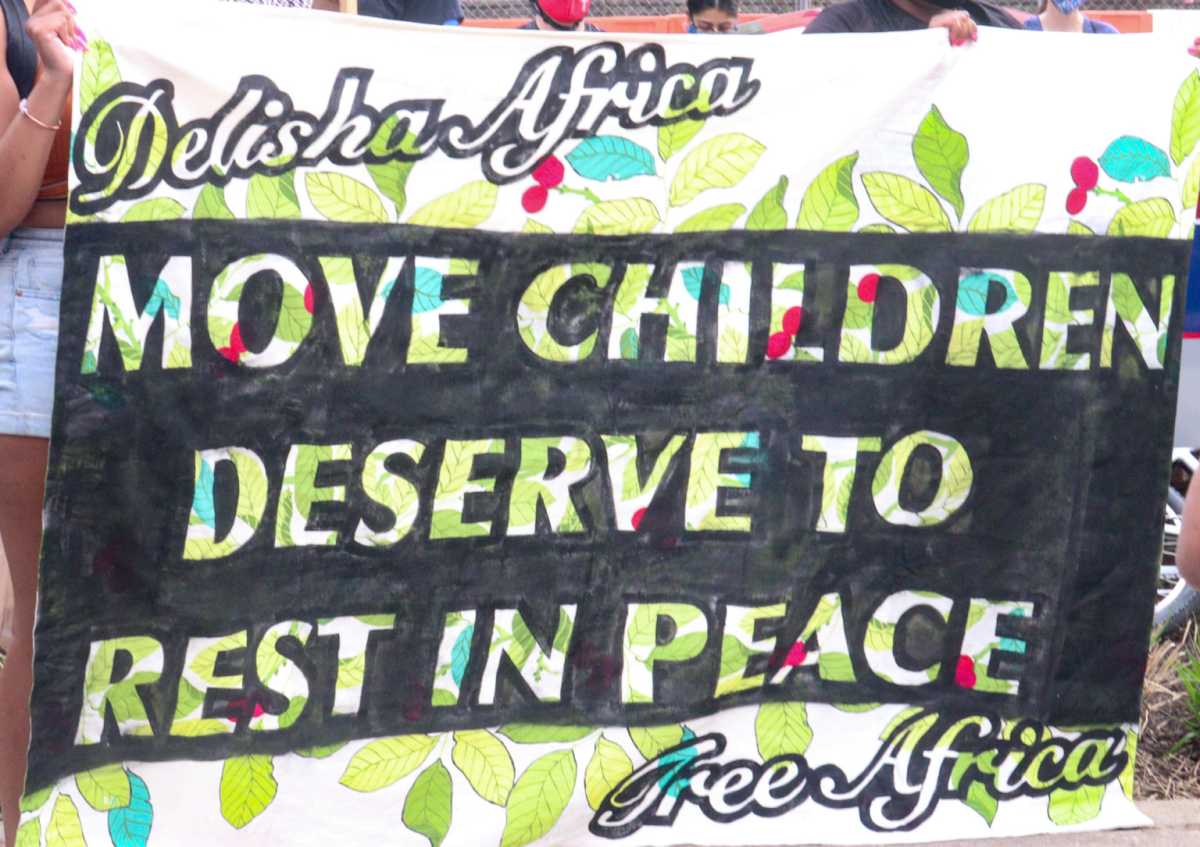

Penn Museum, on its website, said the remains uncovered this week match records for 12-year-old Delisha Africa, also known as Delisha Orr. The museum has not provided more details on the nature or volume of remains recovered.

More than two years ago, Tucker Law Group, a firm retained by the museum to investigate the situation, found that there was “no credible factual or scientific evidence” Penn ever possessed Delisha’s remains. That came after a city report raised questions about whether the museum stored remains belonging to a second MOVE victim.

City Councilmember Jamie Gauthier, whose West Philadelphia district includes both Penn and the site of the bombing, said the museum ignored activists who told the institution’s leaders more than a year ago that Delisha’s remains were still on campus.

“The Penn Museum has demonstrated a profound disrespect for Black life and Black death,” Gauthier said in a statement. “In life or death, it is never OK to use Black bodies as trophies or specimens to enrich an institution.”

Penn Museum, in a statement, said they quickly notified those involved in the MOVE organization, known as the Africa family, when the remains were found.

“Confronting our institutional history requires ever-evolving examination of how we can uphold museum practices to the highest ethical standards,” the museum’s statement continued. “Centering human dignity and the wishes of descendant communities govern the current treatment of human remains in the Penn Museum’s care.”

Attempts to reach current members of the MOVE organization were unsuccessful Thursday. “Should the people that stole and hid her remains be arrested?” the group said on social media in a post that included a news story about the remains and a photograph of Delisha.

Lionell Dotson’s sister, 14-year-old Katricia Dotson, also known as Tree Africa, was killed in the bombing, and news that her remains were still being held at the Penn Museum three years ago focused attention on how deceased MOVE victims have been treated.

“The damage Penn has done is absolutely appalling and unforgivable,” Strom Law Firm, which is representing Dotson in an ongoing lawsuit against the city and university. “It’s time they did the right thing so these children can finally rest in peace.”

Police killed 11 members of the group, including five children, and destroyed more than 60 homes in the Cobbs Creek neighborhood when they dropped explosives on the organization’s headquarters during a standoff nearly four decades ago. The bombing came seven years after a shootout involving the group ended with the death of Police Officer James Ramp.

University of Pennsylvania’s Dr. Alan Mann and Janet Monge, later a curator at the museum, were brought in to assist the Medical Examiner’s Office in identifying remains in the months after the bombing. At the time, there was a dispute between the MEO and MOVE Commission experts over identification of specific bones found at the scene.

Stories published in April 2021, by the Inquirer and Billy Penn, revealed that the remains stayed in Penn’s possession for 36 years. The fragments were used as recently as 2019, during an online course, and were even brought out several years prior for a fundraising event, according to a city report.

A short time later, Philadelphia Health Commissioner Thomas Farley resigned after confessing that he had ordered the MEO to cremate bones found in 2017 related to the MOVE bombing.

A day later, a MEO employee came forward to say the remains – thought to have been destroyed – were boxed in a cold storage room.