Leaders of the MOVE organization believe the Penn Museum may have another set of remains belonging to a third child victim of the 1985 police bombing of the group’s West Philadelphia house.

Last month, museum officials said staff had found remains matching records for 12-year-old Delisha Africa, also known as Delisha Orr. The discovery came two years after news reports first revealed that the institution had been in possession of bone fragments from 14-year-old Katricia “Tree Africa” Dotson.

Mike Africa Jr., MOVE’s legacy director, said the organization has documentation indicating that the museum also has the remains of another victim, possibly Zanetta Dotson, 13.

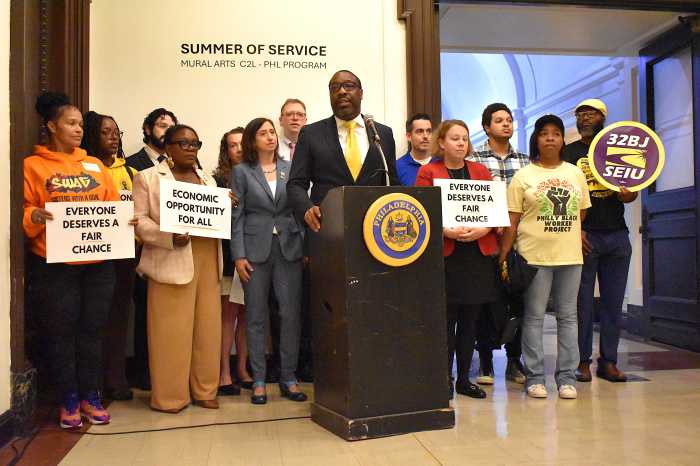

“Potentially, her remains have been studied and processed to the point where they possibly were ground down to dust,” Africa said at a Dec. 9 City Hall news conference organized by Councilmember Jamie Gauthier.

Gauthier, whose district includes Penn’s campus and the site of the bombing on Osage Avenue, has said the museum ignored activists who came forward more than a year ago with information about Delisha’s remains.

“There is real trauma and pain here that needs to be taken seriously and addressed swiftly,” she said. “The Africa family deserves closure, and they should have received that decades ago.”

“The Penn Museum has promised the family and our community to investigate reported information about additional MOVE remains at the museum,” a museum spokesperson said in a statement. “In addition to directly communicating any new information with the Africa mothers, the museum has fully cooperated with all investigations and will continue the ongoing inventory work and rigorous provenance research.”

Delisha’s bones were found while staff were inventorying the facility’s biological anthropology section – an area museum officials promised to search in 2021.

More than two years prior, a law firm hired by Penn to investigate the handling of the MOVE remains concluded that there was “no credible factual or scientific evidence” the institution ever possessed Delisha’s remains. The finding came after a city-commissioned report raised questions about whether the museum stored remains belonging to a second MOVE victim.

“We are still being lied to and continuously harmed and outraged by the fact that our family members’ remains have still not been turned over to us,” Africa said.

Africa said museum leadership told him that Delisha’s remains were discovered inside two unmarked boxes that appeared to have been deliberately hidden, a characterization that was disputed by Penn officials.

“It’s domestic terrorism,” Yvonne Orr, 55, Delisha’s older sister, said Monday. “It is criminal. I want the people held accountable. I want them arrested. I want my sister. I want her to rest.”

Orr told reporters that she has received some remains from Penn. She paid more than $60,000 for testing, only for an analysis to determine the samples were from a dog. Museum representatives said they had no records to validate that claim.

A Penn Museum spokesperson told Metro this week that the institution’s director “has been in direct contact with the Africa mothers since the information about the additional MOVE remains was immediately shared with them on Nov. 12. We are waiting to learn more about their wishes.”

Police killed 11 members of the group, including five children, and destroyed more than 60 homes in the Cobbs Creek neighborhood when they dropped explosives on the organization’s headquarters during a standoff nearly 40 years ago.

In the months after the bombing, two Penn anthropologists – Dr. Alan Mann and Janet Monge, later a museum curator – were brought in to examine the remains amid an identification dispute between the Medical Examiner’s Office and the MOVE Commission’s team of experts.

The bone fragments remained in Penn’s possession for decades. A city report found that the remains were utilized as recently as 2019, during an online course, and were even brought out for a fundraising event several years prior.

After the Inquirer and Billy Penn broke the story about the museum’s remains in April 2021, city Health Commissioner Thomas Farley admitted he had ordered the MEO in 2017 to cremate bones found related to the bombing. He resigned, and, a day later, a municipal employee found the box of remains in a cold storage room.