Most Philadelphia prosecutors feel they have a good amount of latitude in deciding what to offer defendants in exchange for a guilty plea, but few reported having received training on offering plea bargains.

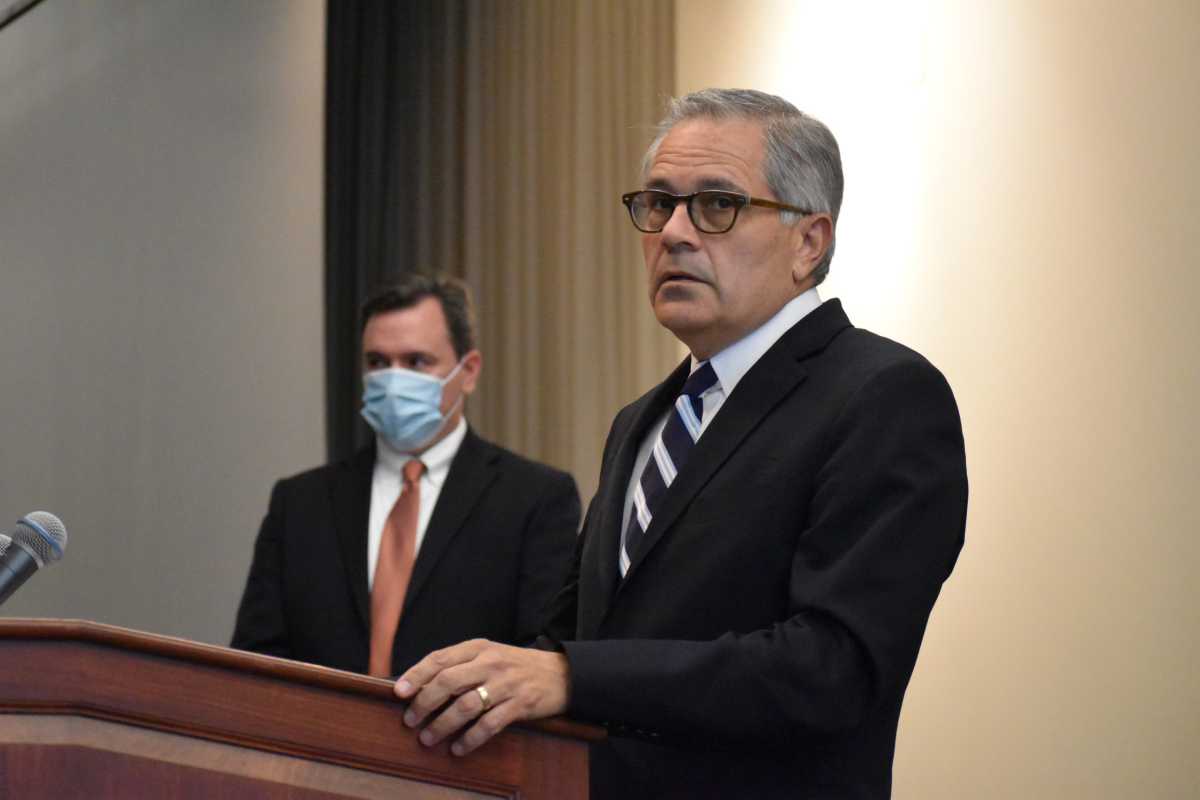

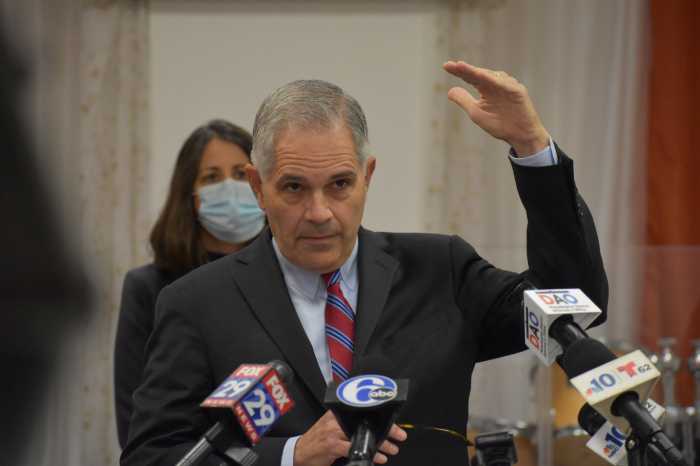

And not all follow — or can even remember — reform-minded policies implemented since District Attorney Larry Krasner took office in 2017.

Those are some of the many findings included in a new 76-page report from the Urban Institute, which spent more than 18 months looking into how negotiated guilty pleas work in the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office.

Nearly 70% of assistant district attorneys, or ADAs, surveyed for the study said they had “a great deal,” “a lot” or “a moderate” amount of discretion when making plea offers to those charged with crimes.

“There is kind of a sense of plea bargaining is an art rather than a science, which I think is very fair,” said Andreea Matei, an Urban Institute policy associate and one of the study’s authors.

“But it’s when you get into some of the more arbitrary, ill-defined metrics and factors in plea bargaining, where you can kind of see racial disparities potentially seeping in,” she added.

Black defendants who accepted plea bargains received prison and probation sentences that were twice as long as white defendants in Philadelphia, the report found. The researchers said Black defendants typically faced more serious charges and had prior records, which affects sentencing guidelines.

Eight out of 10 prosecutors who responded to the questionnaire agreed that structural racism plays a role in the city’s criminal justice system.

Nearly half of the ADAs believe people “sometimes” or “often” accept guilty pleas even if they are innocent.

DAO spokesperson Jane Roh said the research “validates our approach because it shows that the prosecutors we have trained understand the flaws in the system.”

“Since DA Larry Krasner was elected to reform this office, it has been the priority of every unit in the office to train and supervise the fairest and most ethical prosecutors in the history of this city,” Roh said in a statement. “Our mandate is not to win convictions at any cost, but to pursue justice.”

Despite about two-thirds of guilty judgements coming from negotiated pleas, a majority of ADAs reported receiving no professional development on plea agreements from the DAO, according to the report. Matei said the lack of training, as well as the amount of discretion granted to prosecutors, is not unique to Philadelphia.

Among the researchers’ recommendations are that the DAO hold training sessions, collect more data on plea offers and make sure ADAs are adhering to Krasner’s office-wide policies.

Krasner has asked prosecutors to offer sentences that are below the low range of state guidelines for some offenses and push for house arrest, probation or other alternatives when that guidance suggests a sentence of two years or less of imprisonment.

And while the DAO’s goals include an average probation period of six months with a ceiling of one year, the average probation term for those who pleaded guilty in 2019 and 2020 was a maximum of about two-and-a-half years.

“Some people couldn’t even recall some of the policies,” Matei told the Metro. “Others said that it really didn’t apply to their work. And some said that they were more advisory rather than mandatory.”

Roh noted that a small number of ADAs participated in the survey, likely due to a heavy caseload, and some of those who responded work in units not involved in plea negotiations.

Just under 30% of the city’s prosecutors answered the questions, which Matei said is a significant chunk, given that ADAs are not used to, and sometimes not comfortable with, talking about their processes.

The DAO’s sentencing benchmarks and plea policies, among a host of other grievances, were cited in the articles of impeachment against Krasner approved last month in the state House of Representatives.

Krasner has said the impeachment stems from a political disagreement and not any wrongdoing. He filed a lawsuit Friday in an attempt to stop the proceedings.

Matei said the study did not evaluate Krasner’s policies but sought to understand the plea bargaining process, which occurs out of the public eye.

“It’s behind closed doors. Sometimes it’s conducted over email or phone calls,” she said. “It’s hard to understand what’s going on.”

The research was funded by the MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge, which aims to reduce incarceration and racial disparities in the justice system, and the DAO agreed to participate.

It also recommends prosecutors withdraw cases with light evidence instead of offering generous plea agreements and encourages state leaders to reconsider the sentencing guidelines.