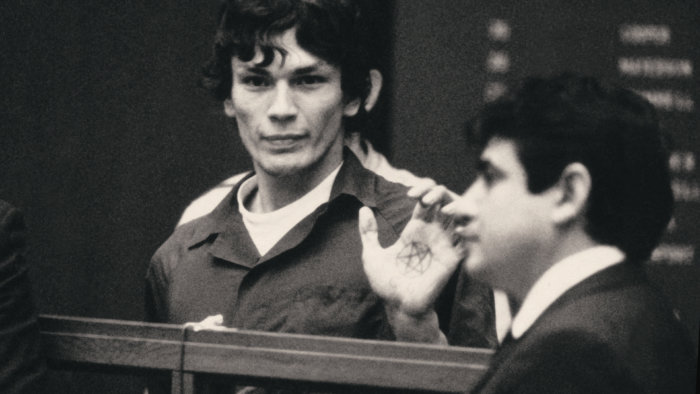

The summer of 1985 was a long and arduous one for the Los Angeles Police Department, but more specifically for homicide detectives Gil Carrillo and Frank Salerno. The partners spent most of the sweltering months up at night, hunting the notorious serial killer and rapist Richard Ramirez, aka The Night Stalker.

Director Tiller Russel, who’s career has been built up by crime docs and malfeasance stories such as this, wanted to cast the narrative in a way that audiences could relate to. By once again humanizing the victims, and by highlighting the human toll this case took on law enforcement that worked it, Russell is able to do just that while also taking viewers on a wild, film-noir styled ride.

Russell sat down with Metro to discuss more on what went into filming ‘Night Stalker.’

What was it about this story that interested you?

My entire professional life has been hunting for great crime stories. All of them are about mapping the criminal underworld and profiling the cops, gangsters and killers that inhabit and that are denizens in that world. Increasingly as I go on, it feels like these stories find me, and that’s what happened with this particular story. Obviously, I knew the contours of the story, the headlines and the rough facts and details of it, but what happened was I was writing for a TV show and my producing partner, Tim Walsh, said, ‘Listen, I just went to dinner with the murder cop that worked the Night Stalker case and I think that there’s an amazing documentary series in this story— do you want to go and sit down with this guy?’

I went and met with Gil Carrillo and we sat down at this knock-around, old-school dive in LA and he began to unfurl the story of what it was like for him to investigate this case during that long, hot and harrowing summer. As soon as I saw how compelling of a storyteller he was and how vivid his recollections were and how much it had impacted him in human terms—and I’m not just saying as a cop, but as a man and a father and a husband— and how profoundly it impacted him, I just thought I had to tell this story.

If you hadn’t met Gil, do you think you still would have chosen to have the story told through the eyes of those who worked on the case?

The decision of point of view or perspective is one of the most important decisions when you tell a story like this. This story had a weird surreal sort of afterlife where after Ramirez was apprehended and brought to the public on trial, there was this circus-like atmosphere that ensued. We didn’t want to glamorize or celebritize Ramirez in any way as popular culture had done in a way, so then it becomes a question of who’s going to tell the story?

Obviously, there were these very compelling, straight out of a James Ellroy novel cops that were working it, so it made sense to anchor it on their point of view and show the toll and impact. It was told procedurally but it also showed how it affected them as human beings. Then also the victims, the survivor’s, the family members who lost loved ones—it’s incredibly dehumanizing what happens to victims in these stories where they become a statistic in someone else’s murder spree or crime spree instead of being treated as a human being who has lived a full and complex life. They are someone who lived, loved and died, so it became important for us to provide an opportunity and a forum for them to bring their loved ones to life. Then, of course, it’s also a larger tapestry of LA—there are these people who have been affected by this story, so we wanted it to be an evocation of the city and its inhabitants.

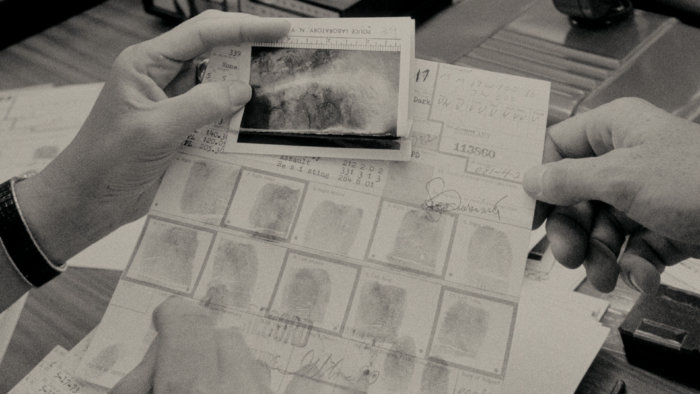

What other filming decisions were made to help get the feel of the time period of the summer of 1985?

This entire story is essentially nocturnal, it takes place at night—that’s when the murders happen, that’s when the cops start showing up to the crime scenes, and so consequently the decision was made that everything we shoot should be nocturnal as if it’s a film noir and is set in locations that could be from 1985. So it’s the nighttime nocturnal look to it, as well as the locations that are evocative of the time and place.

Similarly, every decision is run through that. So, instead of using drones, we decided what would look better in 1985? We went and worked with an amazing aerial company and then used vintage lenses so it’s got that digital, pre-analog look to it. Every choice was deliberate to invoke the time and place and the visual palette from which the story emerges.

What were some of the most shocking facts you uncovered in this story?

There were a couple of things… but that interview with Anastasia Hronas [Night Stalker survivor] and how strong she was and how heartbreaking it was to hear yet how empowered she was—that was a memorable and hugely impactful moment for me. Also, what I did not know going into it, and what the series spends some time articulating is that parallel to the murders, there were these series of child abductions and molestations that had taken place. Those cases never ended up getting prosecuted or adjudicated, that piece had never really entered the puzzle in a significant way. So, the parallel that one man could be responsible for such a diverse array of crimes is what I think made it so challenging for law enforcement.

Overall, what do you hope audiences take away from the series?

For me, this was a very riveting and emotionally powerful and unexpectedly moving experience meeting these people and learning these stories and putting it together. It affected me emotionally in ways I didn’t know it was going to going into it. I hope that for the audiences it is equally complex in that experience where it is on the one hand riveting and on the other hand moving and harrowing at the same time. As a filmmaker and a storyteller, for me it’s about a body of work, and so for anyone who finds this gripping, I hope they’ll move on to find stuff I’ve previously made and still to come and join the ride.

‘Night Stalker’ is available now to stream on Netflix.