It all started one year ago.

On March 10, 2020, the first case of the novel coronavirus was identified in Philadelphia, and, since then, nearly 116,000 city residents have been infected with COVID-19 and 3,169 deaths have been attributed to the virus.

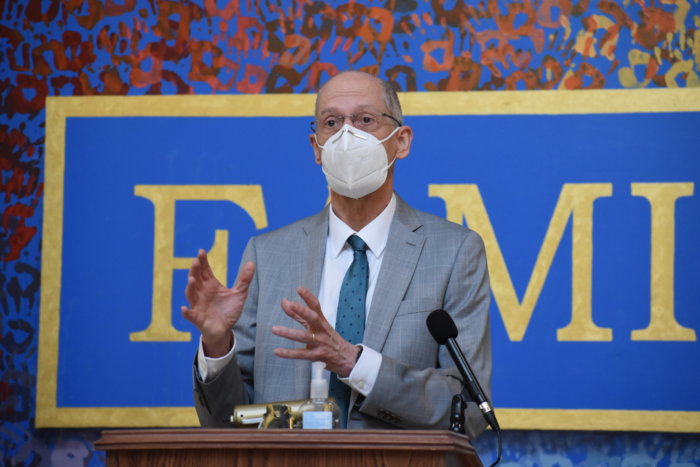

“Frankly, it seems like an eternity ago,” Mayor Jim Kenney said Tuesday.

Social distancing, contact tracing, self-quarantine and a whole host of other terms have entered the national lexicon, and essential workers, another addition to the vocabulary, have been honored while also fighting for increased safety measures.

As a way to look back at the pandemic, Metro has compiled a month-by-month review of the coronavirus and its impact on Philadelphia.

March 2020

After confirming the first COVID-19 case on March 10, Kenney said the city was “ready to manage the situation with the urgency that is warranted.” On that day, officials highly recommended avoiding gatherings of more than 5,000 people.

By March 13, the School District of Philadelphia had announced that schools would be closed the following week, initially for an 11-day period.

A few days later, the Kenney administration ordered all non-essential businesses to close, with restaurants allowed to offer only delivery and pick-up.

Cases began to slowly increase, with a total of 18 people infected on March 18. Farley, on that date, said his department was seeing cases for the first time that couldn’t be tracked back to a source.

Kenney issued a stay-at-home order March 22, which required residents to stay inside unless they were shopping for food, seeking medical attention, caring for family or friends or working an essential job.

City officials announced the first COVID-19 death March 25.

April 2020

By the end of April, Philadelphia had surpassed 10,000 cases and 500 deaths.

Early in the month, the Streets Department said it would begin collecting recycling every other week, initiating an ongoing saga over delayed trash pick-up that continued well into the summer.

SEPTA on April 8 announced that it was drastically cutting service, eliminating about half of bus and trolley routes, closing 18 subway stations and temporarily halting trains on six Regional Rail lines.

The authority has been hit hard by COVID-19, and, during this time, there was even fear that there would be a work stoppage.

Later in the month, Gov. Tom Wolf mandated that essential businesses provide masks to their employees and require face coverings for their customers.

Temple University’s Liacouras Center opened as a field hospital to accept patient overflow on April 20.

May 2020

Early in the month, Philadelphia eased restrictions for the first time, allowing construction projects to resume and golf courses to reopen.

SEPTA restored much of its trolley and bus service and returned to regular weekday and weekend schedules.

City health officials began the work of establishing a system of contact tracing, which was viewed as a key factor as cases started to decline from the spring peak.

June 2020

Philadelphia transitioned to the Yellow Phase of the state’s coronavirus reopening plan.

Retail shops and offices reopened, and outdoor dining was permitted; however, gyms and barber shops remained closed.

Following massive Black Lives Matter demonstrations, the health department advised protestors to get tested for COVID-19 and quarantine for two weeks.

SEPTA began requiring riders wear facial coverings again. An earlier mandate had been reversed after a video circulated showing police dragging an unmasked man from a bus.

COVID-19’s impact on the municipal budget became clear, with the Kenney administration forced to close a $750 million fiscal gap.

July 2020

School district leaders, during this month, said students would return for in-person classes in September to start the academic year.

In response to a backlash from teachers and families, the district pushed the reopening to November.

Meanwhile, the Archdiocese of Philadelphia and some independent private schools pushed forward with plans for face-to-face instruction.

August 2020

Concerns about internet access came to the forefront as it became apparent a majority of students in Philadelphia would begin the year virtually.

On Aug. 6, city officials outlined a $17.1 million plan to provide internet access to low-income families in the city, mostly through Comcast. Kenney called the initiative a “transformational moment.” Thousands of households have since participated in the program.

It was also announced that dozens of centers would open in September to provide a safe place for students with working parents to go during the day for their virtual classes.

Colleges became hotbeds for COVID-19 outbreaks. Locally, Temple University experienced an outbreak of cases, eventually suspending in-person classes for the remainder of the semester.

September 2020

For the first time in nearly six months, restaurants in Philadelphia were allowed to open for indoor dining.

Attention turned to voting, with the looming presidential election. Late in the month, the City Commissioners opened a series of early voting centers, where residents could request, fill out and cast their mail-in ballots.

In November, hundreds of thousands of mail-in votes were counted in a high-tech processing center set up at the Pennsylvania Convention Center.

October 2020

A limited number of fans returned to Lincoln Financial Field to cheer on the Eagles, and the school district looked forward to reopening buildings in November.

Even with some positive signs, cases began to rise, worrying public health officials, who told people not to plan for holiday gatherings with family and friends.

Public school administrators, taking note of the troubling numbers, later pushed back the start date a second time.

November 2020

The Kenney administration reapplied restrictions, closing gyms, museums and high schools and banning indoor dining.

Officials characterized the measures as an attempt to avoid a scenario in which the city’s hospitals would run out of beds.

Gov. Tom Wolf ordered restaurants and bars to stop serving alcohol at 5 p.m. on the day before Thanksgiving.

December 2020

Health Commissioner Thomas Farley blamed a spike in cases on Thanksgiving Day festivities; however, by the end of December, it was clear that COVID-19 spread was trending downward following a November peak.

Wolf, on Dec. 9, told the public he had tested positive. He was asymptomatic.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine received federal authorization, and, on Dec. 16, the first healthcare workers were vaccinated in Philadelphia, which received 13,650 doses that first week.

January 2021

In the first week of January, gyms and museums were permitted to reopen, and high school classes and some outdoor events resumed.

The United Kingdom strain of the coronavirus was detected in Pennsylvania, and state and local officials expressed frustration with the Trump administration over the vaccine roll-out.

Philadelphia began vaccinating residents ages 75 and older, people with high-risk medical conditions and certain essential workers on Jan. 19.

Later in the month, questions began to arise about Philly Fighting COVID, an organization that had run the city’s first mass inoculation clinics.

The Office of the Inspector General this week released the results of its investigation into the health department’s partnership with the group.

February 2021

An effort to install window fans in aging school buildings to improve ventilation drew skepticism and ridicule from teachers and parents.

On Feb. 4, the teachers’ union triggered a mediation process, which lasted the remainder of the month. It was decided that the fans would be ditched, and the first public school students returned for in-person classes Monday.