The Philadelphia Museum of Art’s ‘The Shape of Time: Korean Art After 1989‘ embraces Korean artists experiencing new democratic freedoms in wildly explosive fashion.

Here, 28 living artists “probing Korea’s changing social landscape” through the collective memory of generations under authoritarian regime put forth intoxicating new images regarding faith (Michael Joo’s “Headless” Buddhas with Western cartoon doll heads), security (Kyeok KIM’s “Second Skin” sculpture), beauty (Yuni Kim Lang’s “Comfort Hair”) and beyond.

‘The Shape of Time’ is on display now through Feb. 11, 2024, and to compliment the exhibition, PMA’s Stir Restaurant Executive Chef Hoon Rhee has concocted an elegant, equally vivid tasting menu with special Korean Banchan plates – ripe with meaning, tradition and a couture feel created by ceramics students at Philadelphia’s Arcadia University, under the direction of ceramicist Gregg Moore.

Tied to Rhee’s childhood is his menu’s Hwe (hamachi, seaweed, caviar), and Nakji Bokkeum (octopus, strawberry gochujang, soubise). But, the architecturally-rich Yeonggye-baeksuk (chicken, jook, jujube, chestnuts, gamtae) and his swirl of frozen banana-pudding Bingsu (makgeolli rice wine, soybean, red bean, melon, dduk) is equitable in its artistic focus to the Arcadia students’ serving plates, plates based on traditional design with adjustments made for practicality.

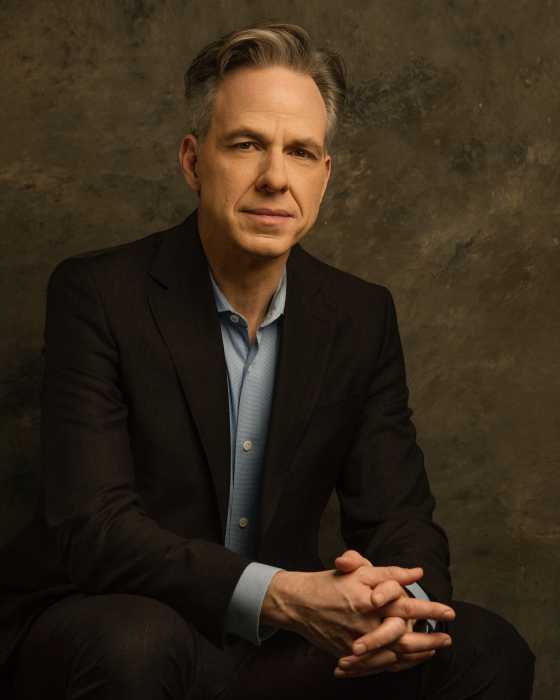

Metro sat down with Rhee to learn more.

You are a contemporary of the artists of ‘The Shape of Time’. In a culinary traditional sense, how does your vision differ from that of your parents’ generation?

For any art that is seen as progressive, it becomes a matter of how much you break from tradition. I only wanted to take “one step” away from traditional Korean dishes, whereas Korean chefs currently at the forefront are taking “two steps” away from tradition where I can’t even recognize what they are creating, even though it tastes Korean to me. They are completely breaking the rules and creating a new context for Korean food, while I am simply bending the rules so that the food is recognizable, but given a new interpretation. This was important to me, to not stray far from tradition, as I knew for this exhibit that I would have both native Koreans who I wanted to show a newer perspective of what Korean cuisine can be without making them uncomfortable, and non-Koreans who I wanted to show where Korean cuisine has been and where it’s going.

Your vision for this tasting menu was a matter of interpretation rather than elevation, elegant but approachable. Can you describe maintaining that balance?

I based this on gut feelings, which was a huge struggle for me and so the balance will differ depending on the diner. The easy part was certain fine dining aspects of the meal. I’ve spent most of my career in fine dining restaurants, so I applied those principles to different parts of the meal whether it was dinnerware or ingredients. Being Korean and having grown up with traditional Korean foods, it did push my comfort level and boundaries whenever I put something traditional, such as the banchan, into a place that seemed “elevated”.

Korean food has always been based on an agrarian society that had to make do with what was available to them and persevere through difficult times… I certainly had to check myself and not hold myself back from stepping away from tradition. Several times I had to ask myself “Why not? Why can’t I put this food here?” and had to reevaluate my own biases. I still look at the menu and struggle with the balance, but I see that as a good sign that I’m in the right spot between the two.

What ingredients were most challenging in regard to ‘The Shape of Time’? You mentioned the “porridge” with the chicken, and how it comes across as “risotto” for Western tastes.

Growing up, things like kimchi and raw fish were something that probably didn’t seem approachable to many Americans. However, with the dining scene the way it is now in the US, not a lot of ingredients would faze the average diner. The menu item that was the most challenging for me was probably the chicken not so much as from a technique standpoint but because I was putting my take on a classic childhood dish that’s considered homey and rustic. Again, it falls in that boundary between traditional and modernism while paying homage to the original.

The architecture of your menu’s items – the lines of your chicken, the swirl of the bingsu – had its own design elements relevant to ‘The Shape of Time’.

Like any art trying to put “refinement” on traditional items, there has to be reference to tradition while leaving room for artistic interpretation based on one’s authenticity. There are subtle artistic nods throughout the meal to Korean tradition. The first course is on a plate that reminds me of the early stoneware of Korean ceramics. The scalloped texture of the chicken reminds me of traditional Korean roofs called Giwa.

The small plates for the banchan, as we discussed, have references to numerous historical pieces. The bronze bowls for dessert are based on traditional bronze dinnerware used in Korea. The overall look of the meal however is my interpretation through my authenticity of being a Korean American who was trained primarily in French Cuisine with other international influences. I loved to draw as a kid and have always enjoyed the visual arts growing up. My wife and I always go to museums when we travel and I consider myself an amateur ceramicist with my own wheel at home. So, the look of the meal in many ways has been a culmination of my experiences.