At the current pace of vaccine distribution, it could take more than a year to vaccinate Philadelphia’s population against the novel coronavirus, the city’s top health official said Tuesday.

Officials are also concerned about preliminary information showing that Black healthcare workers in the city are more reluctant to sign up to receive the vaccine.

And the effects of a feared holiday-fueled spike in COVID-19 cases are beginning to emerge, with Philadelphia’s rates, which had been dropping, appearing to plateau.

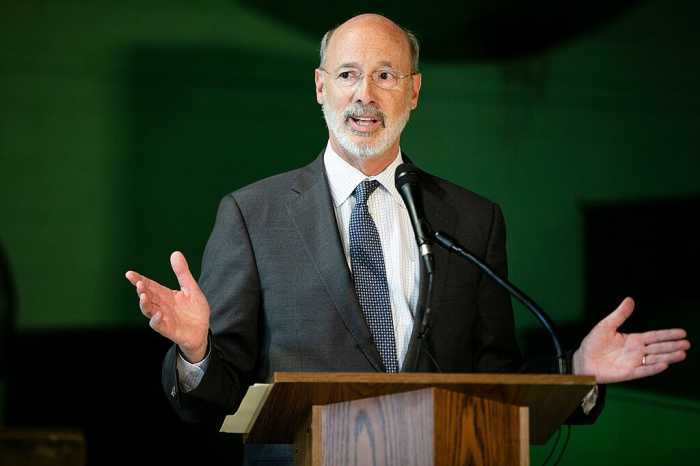

Health Commissioner Thomas Farley said the city will receive just under 20,000 vaccine doses this week, and they have been informed to expect similar shipments for the rest of the month.

“To be clear, in a city of 1.6 million people, this is not enough,” he said during a virtual press briefing. “At this rate, it will take more than 12 months to vaccinate the entire population of the City of Philadelphia.”

Farley added that the city is receiving as much per capita as other areas of the country, suggesting doses are being stretched thin everywhere.

Philadelphia has only administered about 40% of what has been delivered, with 28,476 healthcare workers in the city inoculated so far.

That metric does not include the portion of the city’s allotment diverted to nursing homes, where CVS and Walgreens have been vaccinating residents and employees.

Farley said a lot of steps go into distributing the vaccine, including storage, establishing clinics, and other factors. He said the holiday period also slowed down the process.

“We would like to have more vaccines in people’s arms now, but we are doing the best we can,” he said. “I think people might have an unrealistic expectation.”

There will always be unused doses at any one time because vaccination sites need to keep some on hand, Farley said. With more doses, he added, they would be able to set up more clinics and inoculate more people.

He estimated that there are 100,000 to 130,000 people in Philadelphia who fall into the first category to be vaccinated, also called phase 1a.

Hardly any information has been released by the city about phase 1b. A local vaccine advisory board is still working on who will be part of that group, though federal recommendations include essential workers and people over the age of 75.

If production of the Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech vaccines increases, and other vaccines currently in clinical trials are authorized, the pace could pick up, he said.

“It is going to be a long process,” Farley said. “We do need to just sort of accept the reality of that.”

Last week, shipments arrived at federally-qualified health centers and staff and residents at one nursing home in the city received injections, officials said.

In the coming days, CVS and Walgreens are slated to visit 22 long-term care facilities.

Farley said Philadelphia has reached an agreement with Rite Aid in which the company will administer the vaccine to unaffiliated healthcare workers. The chain will be offering the injection at 26 stores in the city.

He stressed that the shots are for medical employees, such as independent family physicians, who are invited to schedule an appointment. No walk-ins will be allowed.

Montgomery County plans to open a similarly-targeted clinic Wednesday at Montgomery County Community College in Blue Bell.

A troubling trend surfaced Tuesday when Philadelphia officials released the first set of demographic data about who is getting the vaccine, which is voluntary.

Of those who have received the injection, 43% are white; 12% are African American; 10% are Asian; 5% are Hispanic; 10% specified “other”; and there was no racial information for 19%.

Farley said the breakdown, along with statistics provided by a local hospital system, reveals an underrepresentation of minority workers, particularly Black medical employees.

“We believe that they have less trust in the medical care system,” he said. “That’s completely understandable given the history of how African Americans have been treated in this country historically and through today.”

It’s a major problem, he noted, because Black residents have had higher rates of COVID-19 infection and death throughout the pandemic. Farley said he has asked hospital leaders to look into the issue.

Philadelphia averaged 487 new cases a day last week with a 9.1% positive test rate, compared to the prior week’s 570 cases and 8.7%. Probable cases, which are diagnosed through rapid tests, are now included in the averages.

“Before Christmas, the cases in Philadelphia were decreasing fairly well, so the fact that they have leveled off during this past week is an unwelcome change,” Farley said. “I do think that that’s likely caused by social gatherings that happened over the Christmas holiday.”

The city registered 805 additional infections, 111 probable cases and 35 virus-related deaths Tuesday, while Pennsylvania recorded 8,818 new cases and 185 deaths.

Across the state, there are 5,630 people hospitalized with the virus, including 693 in Philadelphia.

It may be only a matter of time before a new COVID-19 variant, first recognized in the U.K. and believed to be more contagious, arrives in the city, Farley said.

The variant has been identified in at least four states, and it may already be in Philadelphia, as recognizing it requires a rarely-conducted specialized test. Only a few laboratories in the city are able to perform such a test, according to Farley.

Anyone who has tested positive and has recently traveled to the U.K. is asked to contact the Department of Public Health to provide a sample.

Farley said a decision on whether to extend bans on indoor dining, theaters, in-person college classes and indoor gatherings will likely be announced by the end of the week. The protocols are due to expire Jan. 15.

Some restrictions were eased Monday, after state measures expired.