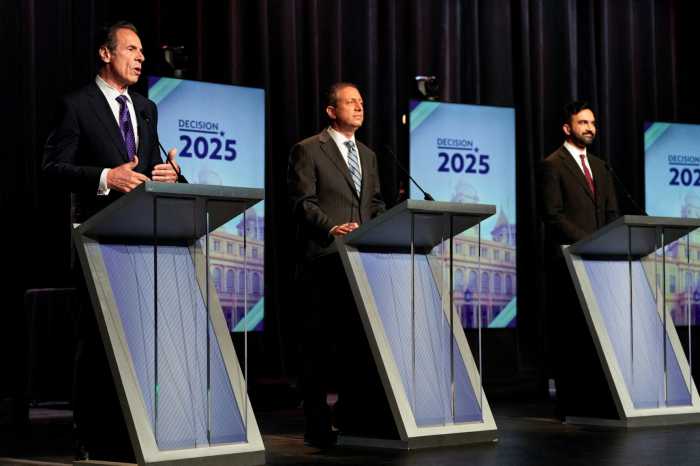

Jason Holliday is the only star of the 1967 film “Portrait of Jason,” presented in a new restoration.

Jason Holliday is the only star of the 1967 film “Portrait of Jason,” presented in a new restoration.

Credit: Milestone Films

On December 3, 1966, filmmaker Shirley Clarke and a modest crew crammed into her two-room apartment in the Chelsea Hotel. For twelve hours they filmed one Jason Holliday, an openly gay black cabaret performer in his early 40s (though he claimed he was thirtysomething). Holliday regaled them with stories from his life — of being harassed by the cops, of being a houseboy for racist whites. His stories are by turns amusing and horrific, peppered with his incessant giggling, as though he was trying to not to cry. (Though he sometimes came close.)

Today, “Portrait of Jason” offers a piercing look at sexual and racial relations before Stonewall — if you’ve been able to see it. And that hasn’t been easy. “Jason” was available on DVD in the U.K., but from a transfer off a faded, dim fifth generation print. The team at Milestone Films — who’ve previously released Charles Burnett’s “Killer of Sheep” and “I Am Cuba,” among many others — spent four years tracking down materials for a new restoration.

Traditionally, the money for restorations has come from a combination of Milestone and the archives they work with. But times have changed. Film labs are closing, and the DVD market has dwindled. Amy Heller and Dennis Doros, who run Milestone, had to turn to Kickstarter last fall to pay for the last leg of the restoration.

“It’s a scary thing to do,” says Heller of the Kickstarter campaign, which was successful in just under 60 days, “especially at a moment when you don’t know what the technology will be when you finish.” Many theaters are abandoning film for digital projection. “Jason” still has some 35mm film prints for screening. And it’s not a good idea to abandon celluloid completely.

“Digital restorations are not archival,” says Heller. “If you restore digitally, you’re going to have a digital file. That could be degraded. It may not even be readable at some point down the road.” Technology changes quickly, and a file made today may not have a program that could read it in the future — even the near future. But for film, all you need is a working projector. “It was important for us to get the film exported to 35mm. That way people will be able to go back and transfer it to the best technology of the future.”

Digital restoration has its issues, too. “The real challenge is to make it look like film,” says Doros. “You don’t want it too clean. You don’t want to remove the grain.” He says a lot of restoration artists wind up cleaning up the grain, in part because it’s a different shape than a pixel: grain are little dots, whereas pixels are square. “It’s a little harder to keep the grain in, but it’s not difficult.”

Also important was trying to respect the look Clarke was going for. “I don’t want to say something corny, like we were channeling her spirit,” Heller says. But they wanted to keep it as Clarke would have wanted. “Shirley wanted it to look rough. That’s why it looks like outtakes.” They had Clarke’s daughter Wendy, who was close to the production, on hand to ensure they didn’t make it look too “good.”

“Portrait of Jason,” which will run theatrically at IFC Center, is still thrillingly intimate, both of a person and an era when homosexuality was illegal. (Anti-sodmoy laws were still on the New York books till 1983.) “It was repressive of the whole culture,” Heller says. “How do you mee other people if you can’t go anywhere and be yourself? There were so many oppressions against the day-to-day life of a guy like Jason.”