In Part Three of Metro’s three-part series examining the overpopulation of the city’s prison system, the racial demographic and mental health of the inmates is examined. You can read Part One here, and Part Two here. They’re usually broke.

They’re typically mentally ill or addicted to drugs or dependent on alcohol.

And they’re black.

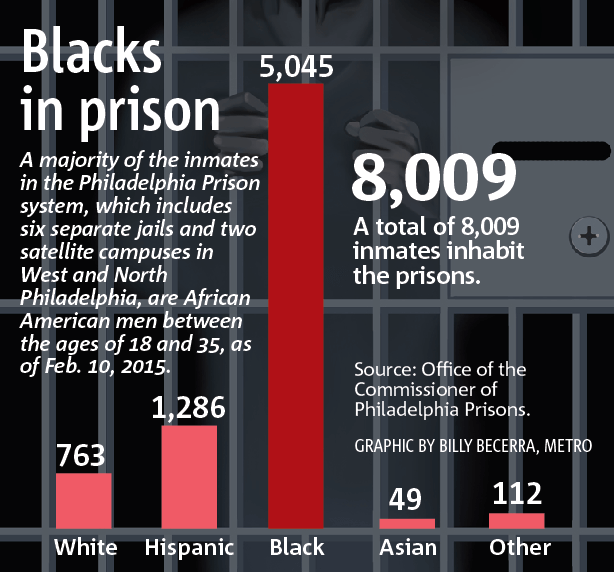

“Racially, it’s generally African American, Hispanic and White,” Philadelphia Prisons Commissioner Lou Giorla said of the prison’s population, “in descending order.” According to the most recent data from Giorla’s office, the Philadelphia Prison system is filled with mostly African American men.

The six jails and two satellite campuses that makeup the city’s system contain a total of 8,009 inmates.

Approximately 5,045 are African American men. And 3,358 of those black male inmates are between the ages of 18 and 35.

According to District Attorney Seth Williams, Chief Public Defender Byron Cotter and Giorla, a majority of the inmates are not only awaiting trial, but they are also suffering from a mental disability, or are addicted to drugs or alcohol. And, most likely, after they are released from prison they commit another crime and walk back through the front doors. Why is this the case, and how can it change?

Education

“What is the No. 1 thing that people who get arrested in Philadelphia have in common?,” Seth Williams asked. “They dropped out of high school.”

High school drop-outs are eight times more likely to go to state prison than graduates, Williams said, and high school drop outs in Philadelphia are 20 times more likely to be a homicide victim.

So the best way to reduce the population, and the best way to reduce crime in this city, is to keep kids in school and to watch for warning signs, he said.

“That starts with early childhood education,” he said. “It means when you discipline kids in school they stay in school as opposed to getting suspended and hanging out on the streets for three days.” Warning signs: students that have chronically unexcused absences.

“Generally, it doesn’t start off that the kid is a rebel in anyway, it’s just there is some disfunction in the family that has to be addressed,” he said. “And often, it’s because the child has a behavior issue because they weren’t socialized appropriately before they started here in first grade and so they’re not ready to begin learning and they fall behind and it’s a snowball effect.” Mental illness

One third of the city prisons population is mentally ill, according to Lou Giorla, and 13 percent are seriously mentally ill.

“Many of those individuals, even though they commit crimes, are not competent,” Giorla said, “they require some community supervision and assistance.”

Giorla said chronic mental illness or medical issues really affects inmate behavior. The issues affect an ability to work, may strain family relationships and their ability to obtain resources in the community. The district attorney’s office and the courts work together to send inmates to mental health and addiction treatment to try and attack the major issues.

A holistic view of the offender would be helpful, Giorla said, but it’s also expensive and time-consuming, “and in some cases it’s unsuccessful,” he said.

“One of the hardest things to deal for people in the treatment community is the recidivism rate and the dropout rate,” Giorla said. “They’re high.”

These are are high-risk individuals who in many cases have had these problems most of their lives and they can’t be corrected in a day.

“People get overwhelmed, and burnout trying to render these services because the successes are small, they’re few and far between,” he said. “But some of the ones you have are amazing.” Overpopulation

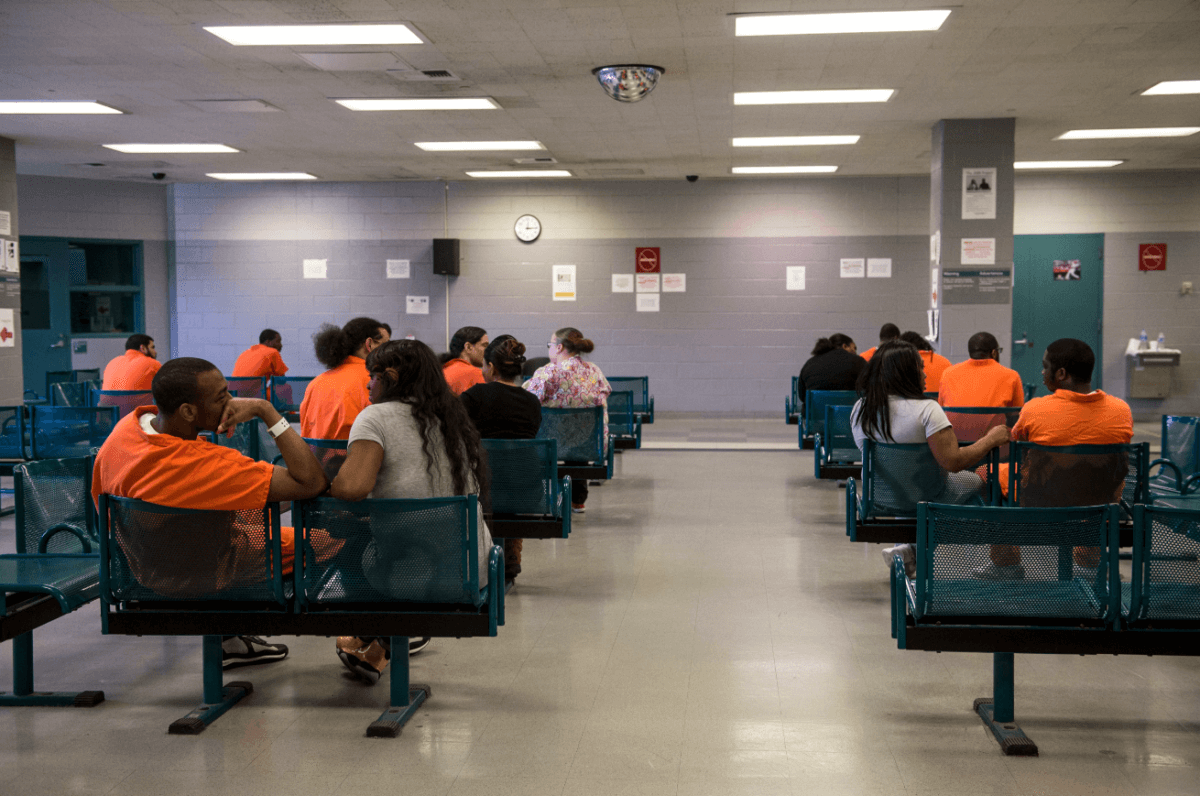

Overpopulation is always an issue, Byron Cotter said, but in order to keep them out you need to help them on the outside. They need: Jobs, drug treatment, and, most importantly, housing.

“We’re trying to work on reducing the clients that don’t really need to be in jail that It would be better for them to be in a drug or job program,” Cotter said. “You need to get them out, but also make it possible that they have the things that they need to prevent them from coming back,” he said. To fight the overpopulation, Seth Williams said, his office has created programs that can direct offenders who may take up space in a jail and put them in a program immediately after arrest to try and avoid a prison sentence and keep another body out of jail. “Instead of clogging the courts and the prison with individuals that they believe can accept responsibility for their criminal behavior, and at the same time, address the underlying causes of their criminal behavior,” he said. “By addressing the root causes of their criminal behavior will also save us in future victimization costs,” he said.