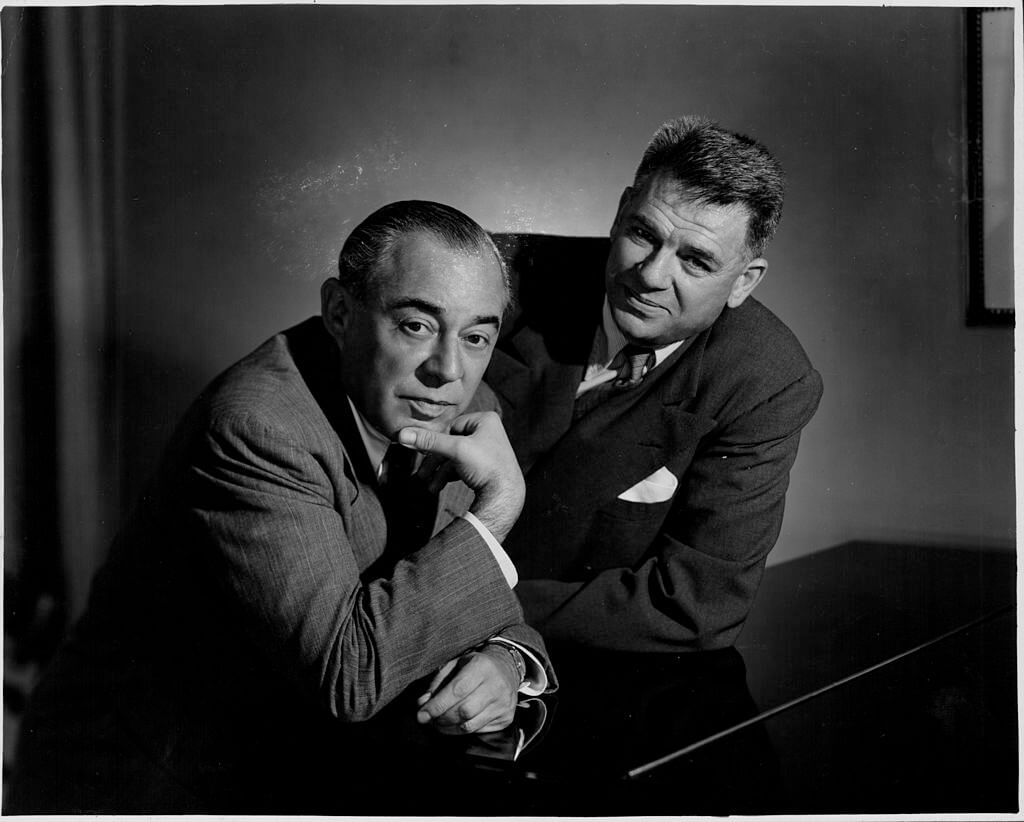

Whether you’re a fan of musical theater or not, you’re already familiar with the work of Oscar Hammerstein II — “South Pacific,” “Oklahoma!” “Carousel” and “The Sound of Music,” to name a few. The legendary lyricist’s partnership with composer Richard Rodgers remains the most successful collaboration in musical theater history. What you may not know, however, is that Hammerstein wrote the lyrics and books to these now classic musicals, not in New York City, but on Highland Farm in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. “Oscar and his wife Dorothy were living in Great Neck, Long Island, at the time, and she never liked it,” said William Hammerstein, Oscar’s grandson and CEO of Oscar Hammerstein’s Highland Farm Inc., an organization dedicated to transforming the site into a museum. “Dorothy also thought Oscar, who loved the country, would benefit both personally and creatively,” he adds.

The family moved to Highland Farm in 1940, when Hammerstein was in the process of winning Best Song at The Academy Awards for “The Last Time I Saw Paris,” an honor that outraged him and his writing partner, Jerome Kern. “They wrote it as a stand-alone song and it got picked up for the movie. After they won, they lobbied the Academy to change the rules so that only songs written for a movie specifically could qualify,” revealed the younger Hammerstein. “He could have cost himself six or seven Academy Awards, but back then principles mattered. “It was a different time. That’s one reason why we need to bring kids here. They need to hear that story and many more.”

According to his grandson, Oscar Hammerstein II was more than a lyricist and dramatist — he was very active in nonprofits.

“Every day he’d give seven hours to the theater and one hour to society,” he said. “Oscar was a co-founder of the California Anti-Nazi League in 1935 — years before Hitler invaded Poland. There was a committee to end Jim Crow in baseball — he was on that. He was a proponent of the United Nations before there was a United Nations.” Hammerstein and Eleanor Roosevelt helped each other with their pet projects, his grandson said. “Everybody wanted Oscar to write their persuasive documents to help raise money because he was the best. He was an idealist and God knows a great writer.” At its peak, Highland Farm spanned 72 acres and boasted a swimming pool, tennis court and corn fields “high as an elephant’s eye.” But the Hammersteins didn’t keep to themselves — they were very much a part of the local community. “Oscar had a system of flags on the street to communicate with the neighborhood kids when it was OK to play on the property. But if he was in deep thought and in the middle of serious writing time, he had a flag that said stay away,” Hammerstein said. One of those neighborhood kids ended up being Stephen Sondheim, who called Hammerstein a “surrogate father” in an interview with the Telegraph. When the 15-year-old Sondheim asked for honest feedback on his first musical, Hammerstein called it “terrible” but broke down why it didn’t work. “The principles of everything I’ve written ever since can be traced back to that afternoon,” Sondheim said. While Oscar Hammerstein’s home at Highland Farm is of vital importance to musical theater history, it is currently not landmarked, and its future remains uncertain.

After Hammerstein passed away there in 1960, Dorothy sold the property and it fell into disrepair.

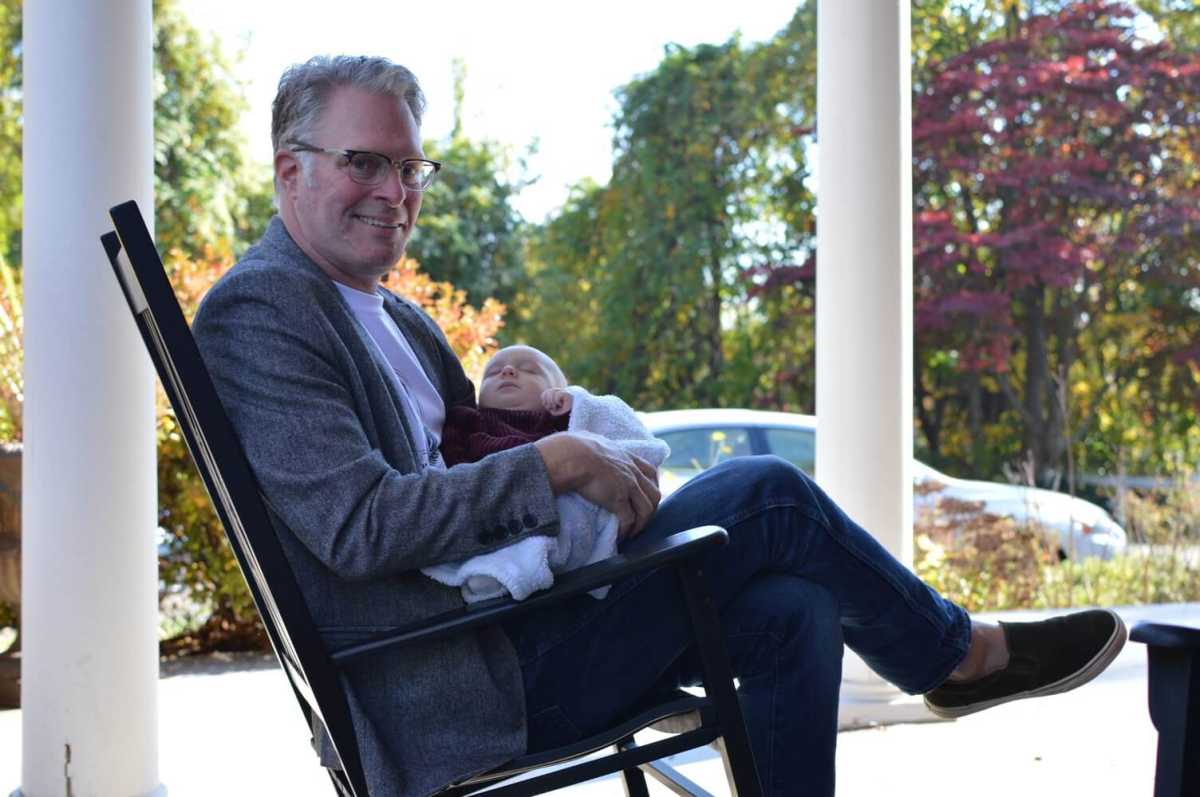

“It changed hands many times,” said current owner Christine Cole. “When I saw it, a developer was renting it out on a month-to-month basis to anyone who wanted it. A local punk rock band had rented it to do a music video and trashed it. The windows were boarded up — cigarette butts and beer cans everywhere.” After renovating the house, Cole opened it as a bed and breakfast in Oscar Hammerstein’s honor, until William Hammerstein reached out about transforming the property into a museum. “Within a year of purchasing, I started meeting with community members about how to preserve it but it wasn’t until Will came along that all the ideas took hold,” she said.

Though lovingly cared for, there are still more hurdles to overcome. In 2006, Highland Farm was approved for a four-lot subdivision by area developers and these plans will remain in effect until the museum opens. William Hammerstein is currently fundraising for the museum project through his nonprofit, Oscar Hammerstein’s Highland Farm Inc. and is attempting to raise $500,000 by Dec. 31.

“The immortal works Oscar Hammerstein created, and the life he lived at Highland Farm in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, have touched countless millions of people around the globe. That makes it a historic site of great significance,” he said. “With the recent zoning approvals we received, there can be a beautiful museum to shine a light on a very good guy with an amazing life story. It’s a great chance to teach future generations that you can change the world through hard work and civil discourse.” For more information on how you can help save Highland Farm and a piece of musical theater history,visit their site.