Philadelphia-based organizers are adopting a broad, multi-pronged approach to defending the slavery exhibits at the President’s House, a site within Independence National Historical Park that has been reportedly targeted by President Donald Trump’s administration.

Activists expected changes to the area to be implemented last week, based on an earlier directive from Interior Secretary Doug Burgum, who visited the park on Friday. However, the area remained unchanged, as of Tuesday.

“We know that nothing happened on September 17 because of pushback,” Michael Coard, of the Avenging The Ancestors Coalition, said. “I’m not going to say what kind of pushback, but I will tell you there was pushback.”

Coard and other leaders of the newly-formed President’s House/Slavery Memorial Alliance met with stakeholders during a lunchtime Zoom session to provide an update on the situation.

Also an attorney, he suggested the group is “ready to pull the trigger” with a lawsuit, if and when the Trump administration removes or alters the President’s House.

To that end, Coard encouraged members of the coalition to “downplay” any suggestion of an alternate home for the exhibits, saying talk about relocation could harm efforts to obtain a federal court injunction.

“That site is the only President’s House,” Coard added. “So we don’t want to talk about alternate locations, because that feeds into the argument of the White House that it doesn’t have to be there. But damn it, it does have to be there.”

‘Paradox between slavery and freedom’

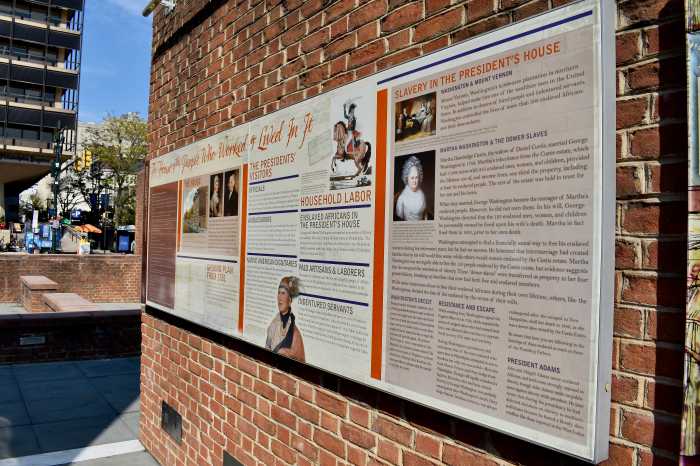

On Tuesday morning, tourists perused the informational panels, which sit in front of the entrance to the Liberty Bell Center at 6th and Market streets.

“This is what Trump wants to remove,” a woman told a girl as they reviewed a section entitled “Dirty Business of Slavery,” which provided context on the transatlantic slave trade.

The President’s House exhibits “examine the paradox between slavery and freedom,” the National Park Service states on its website, with a particular emphasis on the nine enslaved individuals George Washington brought to Philadelphia when he lived in the house as the nation’s first president.

Greg Barnes, 91, of Old City, sat on a stool with a “Ready to Resist” sign hanging from his neck. He said he has been demonstrating at the President’s House daily for the last week and plans to continue as long as the weather holds out.

“I’m a Quaker. That pretty much explains it,” Barnes told Metro when asked why he was protesting. “I feel I owe it to my Black brothers and sisters.”

‘What we do is critical’

NPS officials said Trump “has directed federal agencies to review interpretive materials to ensure accuracy, honesty, and alignment with shared national values.”

“Actions as they relate to President’s House in Philadelphia are ongoing, and it would be premature to provide a comment,” said Elizabeth Peace, a spokesperson for the agency, which falls under the U.S. Department of the Interior.

In March, Trump issued an executive order that called for the restoration of Independence Hall and directed his administration to remove “descriptions, depictions, or other content that inappropriately disparage Americans past or living (including persons living in colonial times)” from all national parks. A similar order, issued by Burgum in May, provided a timeline for the implementation.

Federal employees have flagged at least 13 display panels at the President’s House, according to NPR, and the New York Times reported last week that Trump officials “plan to substantially alter” the exhibits.

“Jimmy Kimmel and those folks fought and got their show back on,” Rosalyn McPherson, a leader of the President’s House/Slavery Memorial Alliance, said on Tuesday’s Zoom call. “I like to think that we are doing the same thing here. We are not taking this sitting down.”

Members of the group discussed ways to use activism, political pressure and the law to defend the exhibits. There are also plans to convene faith leaders, academics, archaeologists and others as part of the effort.

“What’s happening in Philadelphia is being watched by other sites around the country, because we are light years ahead in the sense of organizing,” said the Rev. Mark Kelly Tyler, of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. “What we do is critical, not just for us, but it also lays a strategy and groundwork for other sites who also want to do likewise.”

Coard’s ATAC was formed in 2002 to advocate for the installation of the slavery exhibit when a project was announced to move the Liberty Bell to its current location. Archeologists uncovered sections of the long-demolished home’s foundation – parts of which remain visible through a glass enclosure – and the site officially opened 15 years ago.

Around 40 people attended Tuesday’s Zoom meeting, among them former Mayor Jim Kenney, and a second session is scheduled for Wednesday night.

“I think this is very, very important to the accuracy of our country’s history,” Kenney said. “I would like to see every elected official lining up because I think part of the problem with this president is that people think you can placate him. You’re never going to placate him. He may leave you alone for a while, but eventually he’s coming back.”