Linda Moser doesn’t venture more than a room away when her 14-year-old son Adam is logged on for his virtual classes.

Adam — who Moser calls her “6-foot toddler” — is on the autism spectrum and has an intellectual disability. He requires one-on-one support, whether he is in the classroom or learning from home.

“He needs someone to make sure that he goes in the building, goes where he’s supposed to,” said Moser, who lives in King of Prussia. “You can’t not hold his hand at times.”

Virtual schooling has impacted every family and educator; however, those with children who have autism or other intellectual disabilities have had to face down unique challenges.

Parents and guardians have had to take on additional responsibilities, technology has presented its own hurdles, and there is concern about how the absence of in-person communication will affect interpersonal skills.

That’s not to say there haven’t been successes. Students with special needs have adapted to the technology, and some have even thrived.

It’s been nearly a year since many children, including those attending public school in Philadelphia, have been inside a classroom, though signs indicate an in-person return is near.

The School District of Philadelphia will be bringing students into schools for the first time Monday. Six high schools will be opened up for face-to-face assessments for students with disabilities.

Other districts, including Upper Merion, where Adam is enrolled, are pushing ahead with larger-scale reopenings.

Michelle Ettorre, a K-2 autistic support teacher at Lamberton Elementary School in Overbrook Park, said she has noticed regression in her students, particularly with writing.

“They definitely 100% need in-person learning,” Ettorre said. “When we were at school, they could write a paragraph. Now, it’s like pulling teeth to get them to write one sentence.”

A big part of Jenn Connelly’s curriculum is taking her students on class trips. She teaches a life skills class for 18-to-21-year-olds with developmental disabilities at George Washington High School in the Far Northeast.

They go on SEPTA and visit grocery stores, restaurants and work sites to learn real-world skills.

Since March, Connelly has guided her students through virtual activities, such as online shopping, but it’s not the same.

“I don’t know if they’re making the real connection because we’re not going out into the community,” she told Metro. “I don’t know if it’s really transferring.”

A few of her students have found it easier to communicate over Zoom, she said. Others have really shut down, and she struggles to get more than one-word answers out of them.

“There’s definitely regression in comprehension and communication when it comes to having full conversations,” Connelly said.

Ettorre has worked hard to stifle boredom. She utilizes field trips, taking her phone to police stations, convenience stores and even the zoo to keep them engaged.

She has two nonverbal students, and virtual learning is simply “not working” for them, Ettorre said.

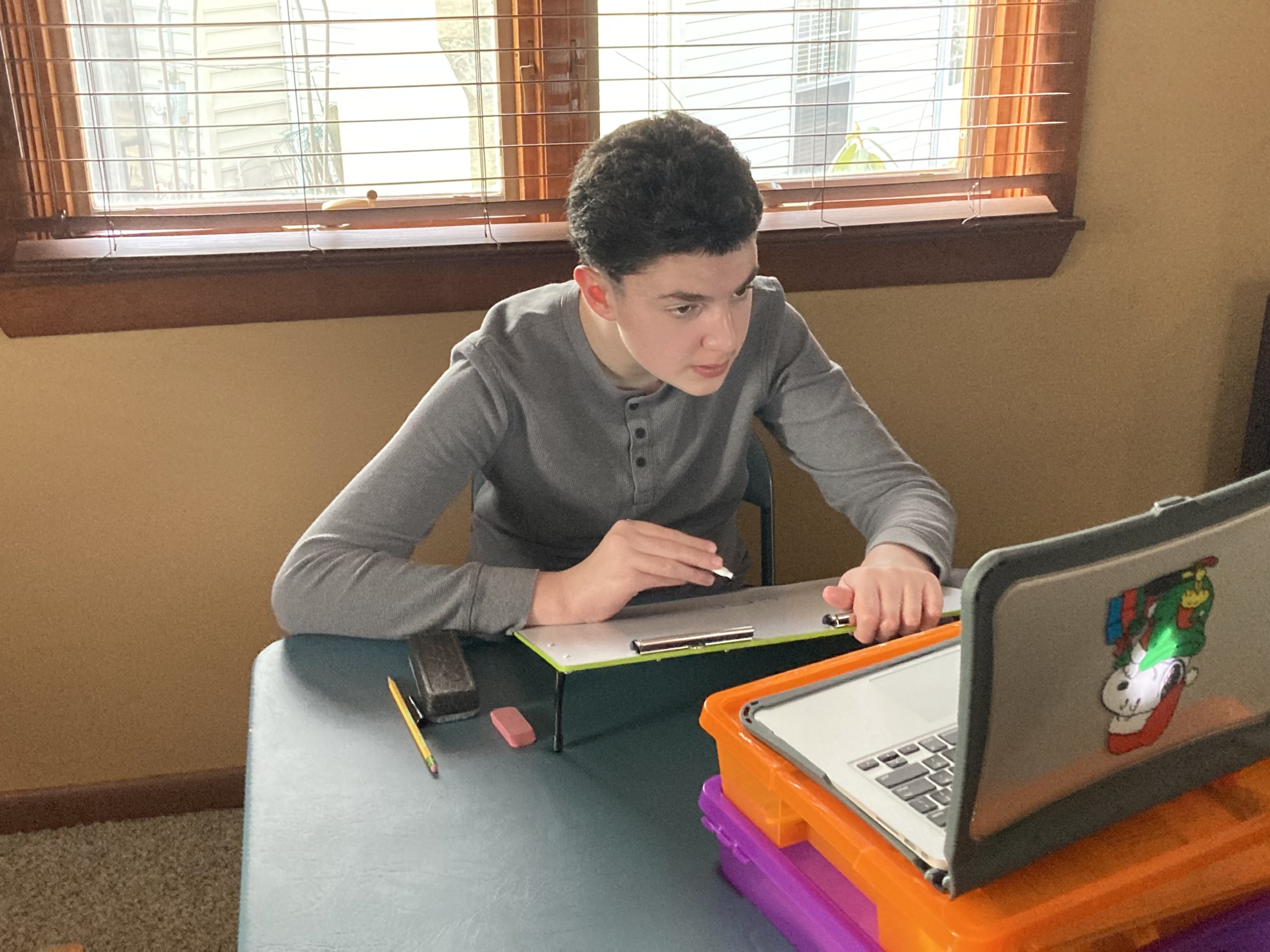

Moser worried Adam wouldn’t be able to handle the transition to a computer.

While in middle school, he had a school-issued iPad, which he enjoyed using for certain tasks. The Upper Merion Area School District gave him a laptop, but also allowed him to hold on to the tablet when he went to high school, Moser said.

The laptop has not proven to be a problem, even though he still likes to have pen and paper in hand. Adam, like nearly everyone else, has begun to master Zoom.

Ettorre said her class’s tech savviness has “blown her away.” It took months, Connelly said, but her students have become comfortable with the virtual platform, and their attendance rate is better than most others at Washington.

“They want to learn. They want to be on, and they want to see their friends,” Connelly explained. “I think once they figured out the pattern of how to access the classroom, they’re there every morning, from beginning to end.”

Lower-functioning students have to rely more on their parents, who, in many cases, are tending to younger children or trying to work from home themselves.

Connelly said she has been instructed to train parents. However, in her experience, most aren’t eager to be taught.

“The parents are tired. They’re drained,” she said. “They’re not used to it. They continuously say, ‘I’m not a teacher. I’m not a teacher.’’

Ettorre said, though her Lamberton parents are very involved and willing to help, they are “definitely overwhelmed” and ready to send their kids back to school.

Moser feels lucky. She is a homemaker and empathizes with parents who have to simultaneously work and teach.

“I can’t imagine trying to do that with a child like Adam,” Moser said. “I wouldn’t be able to do it.”

Adam receives speech, occupational and physical therapy. The later two have been challenging in a virtual setting, with therapists attempting to explain the various exercises to Moser over video conference.

“I get a lot of feedback, and they help me and everything else, but it’s not the same as them being with my child,” Moser said.

Companion services have also been offered virtually by the School District of Philadelphia, which has worked with families to develop individualized digital learning plans, said ShaVon Savage, of the district’s office of specialized services.

Students will begin visiting the district’s six specialized service centers Monday to complete special education assessments.

About 600 students have been prioritized for the appointments based on their need to be seen in-person. It’s likely the centers will remain open and provide additional services to students with disabilities after the assessments are complete.

Staff at the centers will be tested for the coronavirus weekly, and students, who only come in for one session, will be given a rapid test upon arrival.

Superintendent William Hite, during a City Council hearing Thursday, said the district will roll out its phased-in reopening plan this week. PreK-2nd grade students will be the first to come back, followed by students with special needs in grades 3 through 12 and career and technical education students, officials have said.

Connelly said she is “dreading” returning to Washington because safety protocols will likely significantly limit her program.

“We’re still not going to be allowed to go out in the community,” she said. “We’re still not going to be allowed to go on SEPTA.”

Adam could already be back in school. Upper Merion is allowing students in his class to come in for three-and-a-half hours a day, though families can choose to remain virtual.

But Moser didn’t believe it was worth it, and she is concerned about one of her other sons, who has a weakened immune system, catching COVID-19.

“(Adam) can’t social distance,” Moser said. “There’s no way.”