When city agencies foreclosed earlier this year on loans for affordable housing units in Germantown tied to disgraced developer Emanuel Freeman, neighbors hailed it as a turning point. But months later, some of the tenants who were hoping for positive change are instead getting kicked out as living conditions at one site decayed to the point of outright danger.

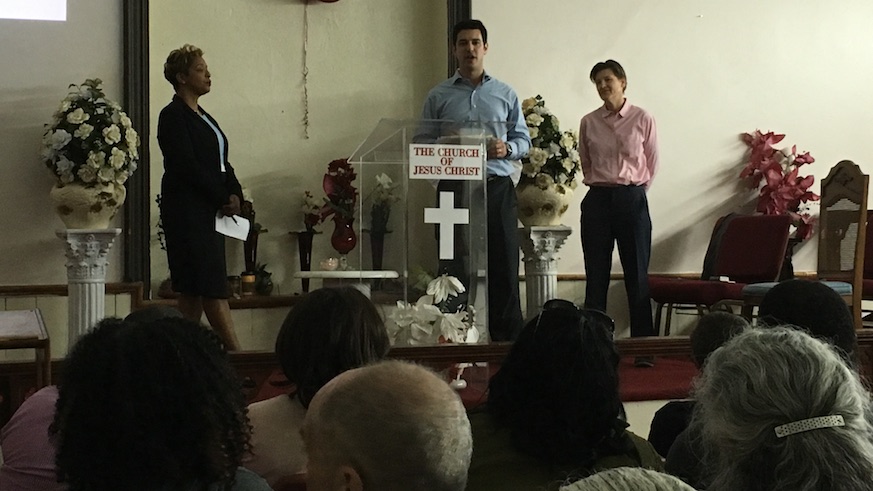

Anna Figueroa, a resident of Hamill Mill II in Germantown, held a tenants meeting to start organizing a call for the city’s help repairing the living conditions she described as an “emergency.”

“I’m fighting this, and I’m getting tired because I’m tired of ‘the process,'” said Anna Figueroa to fellow tenants of Hamill Mill II and other Freeman-linked properties. “The city should have been helping us, because they let this man go on and on and on and on.”

But the next day, they were all told they’d have to leave within a week. The Department of Licenses & Inspections (L&I) ordered the property closed due to hazards including multiple fire safety violations going uncorrected by the building’s owners. While the tenants, who have been promised referrals to public housing, agreed Hamill Mill II was in terrible shape, they were hoping city intervention would mean repair, not removal.

“Why should I move when I didn’t ask to go through this?” Figueroa asked after getting the news. “A lot of people lost money, we were paying rent. … The city messed up. That’s not our fault. You could save a lot of money, just fix the fire stuff, and then we’d still be there.”

Hamill Mill II, a 33-unit affordable housing project assessed at a value of $600,000 and carrying a $30,000 tax debt, is also set to go up for sale at the Sept. 19 sheriff’s auction, with an opening bid of $1,500. It is listed in city records as belonging to Lower Germantown, LP — one of the many holding companies linked to Freeman — and was created as part of a $5 million tax credit-financed affordable housing project involving several other buildings.

The city’s Department of Licenses & Inspections (L&I) ordered the building closed down due to various severe hazards, including a lack of working front-door locks, no working sprinklers, no smoke detectors, empty rooms full of combustibles and other fire hazards. It also had unoccupied rooms covered in severe mildew, the elevator had been deactivated and faulty utilties led some tenants to power their apartments with extension cords from neighboring, unoccupied units.

“It’s at the point we now consider it an emergency. This is just utterly unsafe and unconscionable,” said Karen Guss, a spokeswoman for L&I. “We just can’t let people live in it.”

As of press time, the Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA) and Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority (PRA) were working together to find new housing for the remaining tenants before the tentative Aug. 14 deadline.

The PRA defaulted on four loans to entities linked to Freeman back in March, representing about $9 million in loans including interest and penalties and 45 unlicensed rental properties around Germantown.

PRA and tenants believed those properties included Hamill Mill II. But at a court date in May, PRA lawyers discovered Hamill Mill II had a different owner than they thought, and that they may not be able to foreclose on it.

However, they did secure an emergency receivership for Hamill Mill I, which was vacated and sealed for similar building hazards by PHA’s Philadelphia Asset and Property Management Company (PAPMC). For several dozen other properties, they’re still waiting on receivership hearings as well as initial hearings on foreclosure, which could take years.

“We want to do the right thing for the community and the people who are living in very tough conditions, but we have to wait for the court process,” said PRA executive director Greg Heller. “Our No.1 interest is preserving these properties up to a sufficient standard of quality and maintaining them as affordable housing for the community.”

Under city control

When the PRA decided to foreclose, they rejected an offer from Freeman and his associates to pay off the loan in return for forgiveness of the penalties and interest, saying the decision was made after Freeman’s team didn’t meet conditions required by the payoff structure authorized by the board.

Attorney Gary Perkiss, who represents the ownership group behind the loans, asserted that Freeman is no longer part of the group, and that the investors could and want to pay off the loans and rehab the properties.

“The ownership group is attempting to resolve this with the PRA, has the funding to do it, and their goal is to close on the financing and clean up the properties, rehab the properties and do whatever’s necessary to keep them functioning,” he said.

The PRA responded that Perkiss’ proposal had previously been evaluated by the board and was found lacking in funding to rehab the properties to a sufficient standard.

The properties are among the most visible legacy of Emanuel Freeman, dubbed “The Man Who Duped City Hall” in a famous Philadelphia Magazine expose. Freeman rose to power within the Quaker-founded social service agency “Germantown Settlement,” gradually took it over and wound up managing a social services empire that was estimated to have netted $100 million grants for programs intended to fight poverty and benefit the community.

The funds were funneled into projects across Northwest Philly, including affordable housing, a charter school, programs for children removed from their homes and to address school truancy. But many of the organizations reportedly offered substantial and dysfunctional services, didn’t have proper bookkeeping, and were even blacklisted by some city departments, as others continued to send grants.

In 2010, Freeman’s last major organizations, Germantown Settlement and Greater Germantown Housing Development Corporation, went bankrupt. But many of the affordable housing properties were later found to have been transferred to new entities still under Freeman’s control.

Local attorney Yvonne Haskins recently filed a complaint to the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office over this transfer, which she said was illegal.

“It is outrageous to me that the Freemans have been allowed to abuse these tenants with no one making a referral to the district attorney,” Haskins said. “Tenants have been putting up with this for years. … It’s clear that abuse is continuing.”

Figueroa said even after being relocated, she and other tenants of former Freeman properties deserve compensation for being conned out of rent to live in unlicensed properties and for the recent months in limbo with steadily worsening conditions.

“We’re still fighting. The tenants are already organized,” she said. “Why should we stop fighting? Because they gave us housing? No. This has got to stop. … We have got to stop landlords and the city from treating people the way they’re doing.”