John Marshall keeps a picture of Breonna Taylor in his office at the headquarters of Kentucky’s largest school district, a visual reminder, he says, of the need for curriculum changes that better honor and focus on Black stories.

Taylor, a Black emergency medical technician, spent her senior year of high school at Kentucky’s Jefferson County Public Schools, where Marshall, the district’s chief diversity officer, has been leading a system-wide revamp of teaching materials and practices.

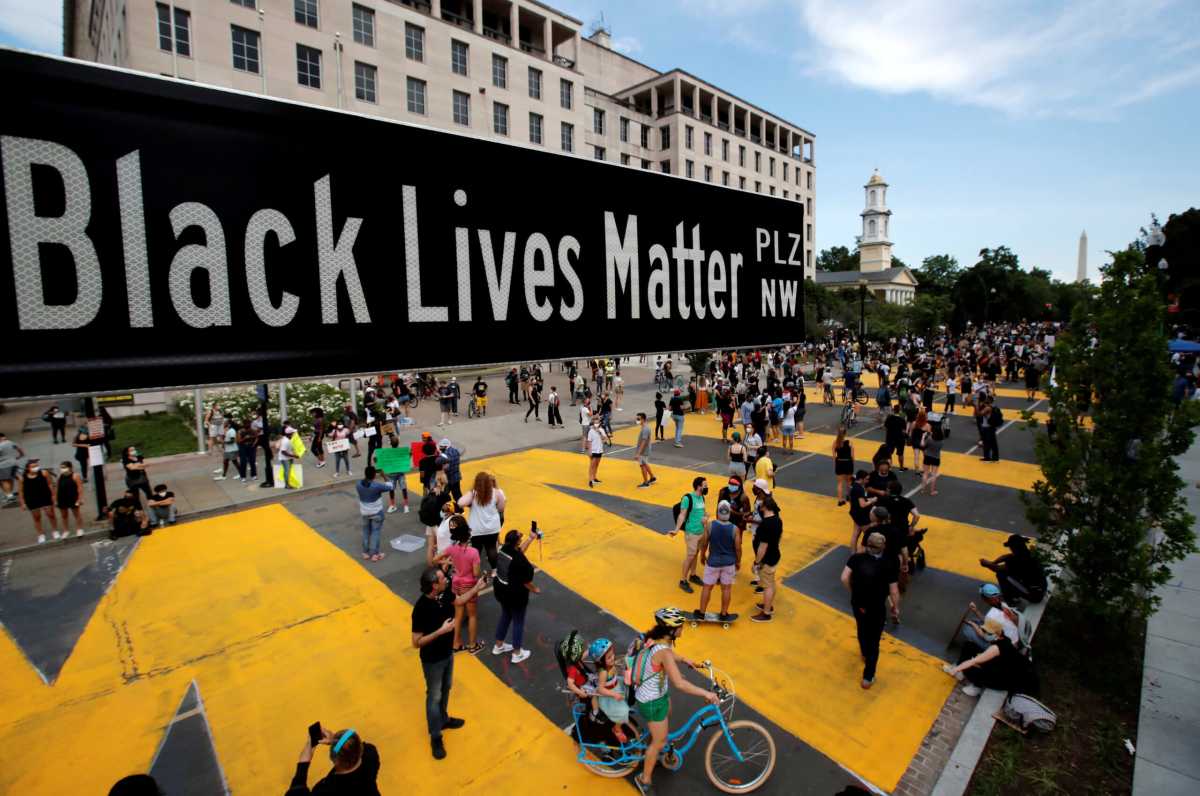

Taylor was shot dead by police officers in March. Her death and that of George Floyd, killed by Minneapolis police in May, and others have set off a national reckoning over race and race relations.

No criminal charges have been filed against the officers involved in Taylor’s death, infuriating many in the school district, where a majority of the nearly 100,000 students are students of color.

For educators in Jefferson County and across the United States, the deaths have jump-started demands for teaching materials and practices that help Black students better understand their history and place in the country.

After a summer of teacher workshops focused on updating curricula, millions of students will return to U.S. classrooms in coming weeks – virtually or in person – that focus more on Black history and experiences, according to interviews with teachers, officials, publishers and others.

“We’re not just talking about a couple of lesson changes,” said Marshall. “We’re getting to the quintessential work of trying to put race, equity and inclusion inside of our curriculum.”

A June survey by the EdWeek Research Center, which is affiliated with the prominent trade publication Education Week, found that 81% of U.S. teachers support the Black Lives Matter movement.

“We can’t control what happens with the police, but we can control what happens in our school systems,” said Michael McFarland, head of the National Alliance of Black School Educators and a superintendent of the Crowley Independent School District in Texas.

Some of the changes don’t necessarily involve new material, but rather teaching the same material from a new perspective.

In the Jefferson County schools, for instance, teachers discussing the Space Race of the 1960s plan now to focus on the Black women mathematicians whose computations underpin modern rocket science.

In Houston, teachers at YES Prep public charter schools will dissect James Baldwin’s iconic book of essays “The Fire Next Time” less as a history of racial struggle and more as a guide for Black students to overcome injustice.

These and other recommendations came after school districts spent summer months updating educational materials because most public school textbooks are only updated by publishers on a fixed schedule.

How and what U.S. students learn about American history depends on the school. The country’s public K-12 education system is run by more than 98,000 local and state school board members, who nearly always have the final say on which textbooks are bought for classrooms.

In 2014, the Texas State Board of Education came under fire https://www.reuters.com/article/us-texas-textbooks/texas-to-consider-mexican-american-textbook-critics-decry-as-racist-idUSKCN11F1G5 when it considered approving a Mexican-American studies textbook that critics decried as riddled with mistakes and demeaning stereotypes. Other school boards either bought different textbooks or didn’t offer the same course.

‘DIFFICULT CONVERSATIONS’

The National School Boards Association, which advises school districts on curriculum changes, said requests for advice on crafting racially diverse educational material doubled this summer from the same period last year.

“They’re making sure teachers are teaching the right history in their classrooms,” said Anna Maria Chavez, the association’s executive director.

Scholastic Corp, which publishes educational material to supplement textbooks, said it has seen a surge in demand for books that focus on diversity and equity.

“Schools are wanting to have these more difficult conversations about race and social justice,” said Michael Haggen, Scholastic’s chief academic officer.

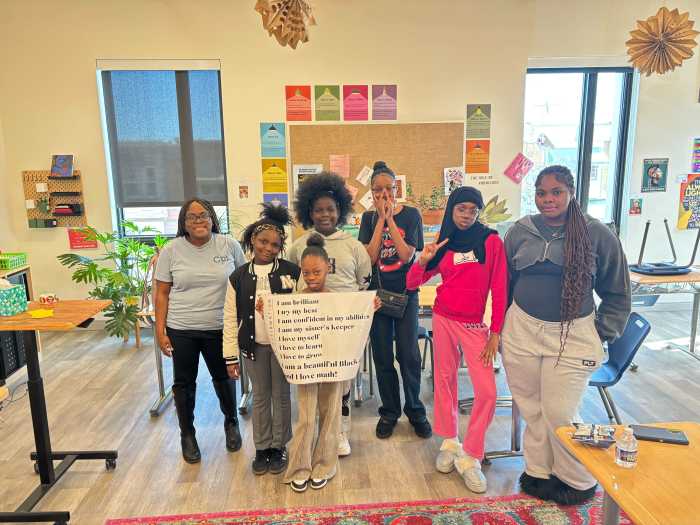

Staff at Houston’s YES Prep said their returning 15,000 students can expect to spend more time reflecting on how the deaths of Taylor, Floyd and others connect to a timeline of injustice.

The goal for YES Prep students, nearly all of whom are Black or Latino, is to consider how they can not only oppose racism, but be part of broader cultural change, said Kiara Hughes, YES Prep’s director of organizational strategy and initiatives.

“This isn’t a singular moment in time,” said Hughes. “This is a fight that people have been fighting for a hundred of years.”