By Jake Spring and Valerie Volcovici

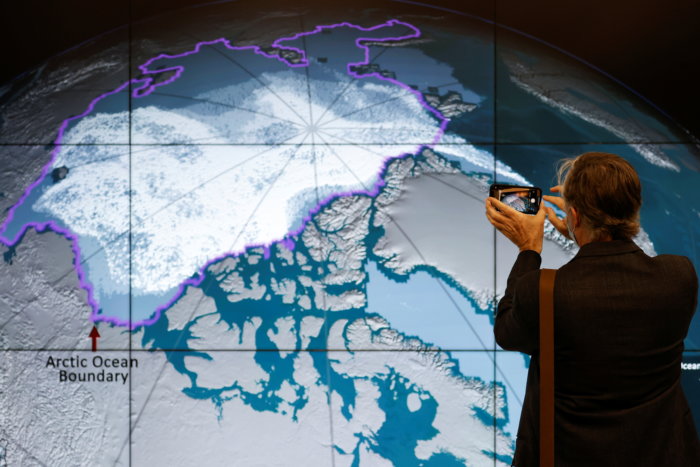

Approaching the final day of the two-week COP26 U.N. climate summit, delegations intensified efforts to strike a deal to tame global warming, with the focus on finding cash to help developing nations cope with its worst effects.

A first draft of the COP26 accord released on Wednesday implicitly acknowledged that current pledges were insufficient to avert climate catastrophe, and got a mixed response from climate activists and experts.

However, a surprise agreement later in the day between China and the United States, the world’s two biggest greenhouse gas emitters, boosted hopes that the almost 200 national delegations can toughen up their collective commitments by Friday.

With a new draft expected in the coming hours, “climate finance”, or help for poor nations most vulnerable to the floods, droughts and rising seas triggered by global warming, is central to the negotiations.

Britain’s conference president, Alok Sharma, said the latest draft conclusions he had seen showed “significant” progress, but “we are not there yet”.

“I’d like to address the critical need to step up efforts today to get to where we need to be to realize substantive outcomes on finance,” he said.

Developing nations want tougher rules from 2025 onwards, after rich countries failed to meet a 12-year-old pledge to provide $100 billion a year by 2020 to help them curb emissions and tackle the effects of rising temperatures.

Wednesday’s draft merely “urged” developed countries to “urgently scale up” aid to help poorer ones adapt to climate change, and called for more funding through grants rather than loans, which add to debt burdens.

The missed $100 billion goal is expected to be reached three years late, undermining the trust of developing nations and making some of them reluctant to make their emissions reduction targets more ambitious.

The sum, which many campaigners say is anyway woefully inadequate, is divided into a part for “mitigation”, to help poor countries with their ecological transition, and a part for “adaptation”, to help them manage extreme climate events.

A more contentious aspect, known as “loss and damage” would compensate them for the ravages they have already suffered from global warming, though this is outside the $100 billion and some rich countries do not acknowledge the claim.

Poor countries say a tax on carbon markets would provide critical support but rich nations, including European Union states, are concerned about the costs.

The conference host, Britain, says the overarching goal of COP26 is to “keep alive” hopes of capping global temperatures at 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels, still far from reach under current national pledges to cut emissions.

Scientific evidence has grown that crossing that threshold would unleash significantly worse heatwaves, storms and wildfires than those already occurring, with irreversible consequences.

The jury is out on whether the Glasgow talks are making meaningful progress towards the 1.5C goal.

Some thinktanks are encouraged by deals struck on issues such as deforestation, curbing the potent greenhouse gas methane, and that Wednesday’s draft addressed the issue of reining in fossil fuels.

Others point to insufficiently clear commitments and timelines, especially from major polluters such as China, India and Russia.

“What we need to know are the deeds, the specifics on the deeds and the accountability to deliver,” said Lindsey Fielder Cook, climate change representative from the Quaker United Nations office.

On Thursday, a fledgling international alliance to halt new oil and gas drilling added six members, but did not get the support of any major fossil fuel producers.

Wednesday’s U.S.-China accord saw a joint recognition of the need to step up efforts over the next decade to curb rising temperatures and new commitments from Beijing on reducing emissions and protecting forests.

Aside from the concrete pledges, which were scant on numbers, most observers agreed the significance of the deal was that two global powers often at loggerheads, were cooperating.

“The real good news of that agreement is that they spoke, because if you look into the content it’s a series of general commitments to agree a road map for climate,” said Italy’s Ecological Transition Minister Roberto Cingolani.

The Climate Action Tracker research group said this week all national pledges so far to cut greenhouse gases by 2030 would, if fulfilled, allow the Earth’s temperature to rise 2.4C by 2100.

On the day before the Glasgow conference COP26 closes Pope Francis, an ardent climate advocate, sounded a warning in a letter to Scotland’s Catholics, saying: “Time is running out”.

Reuters