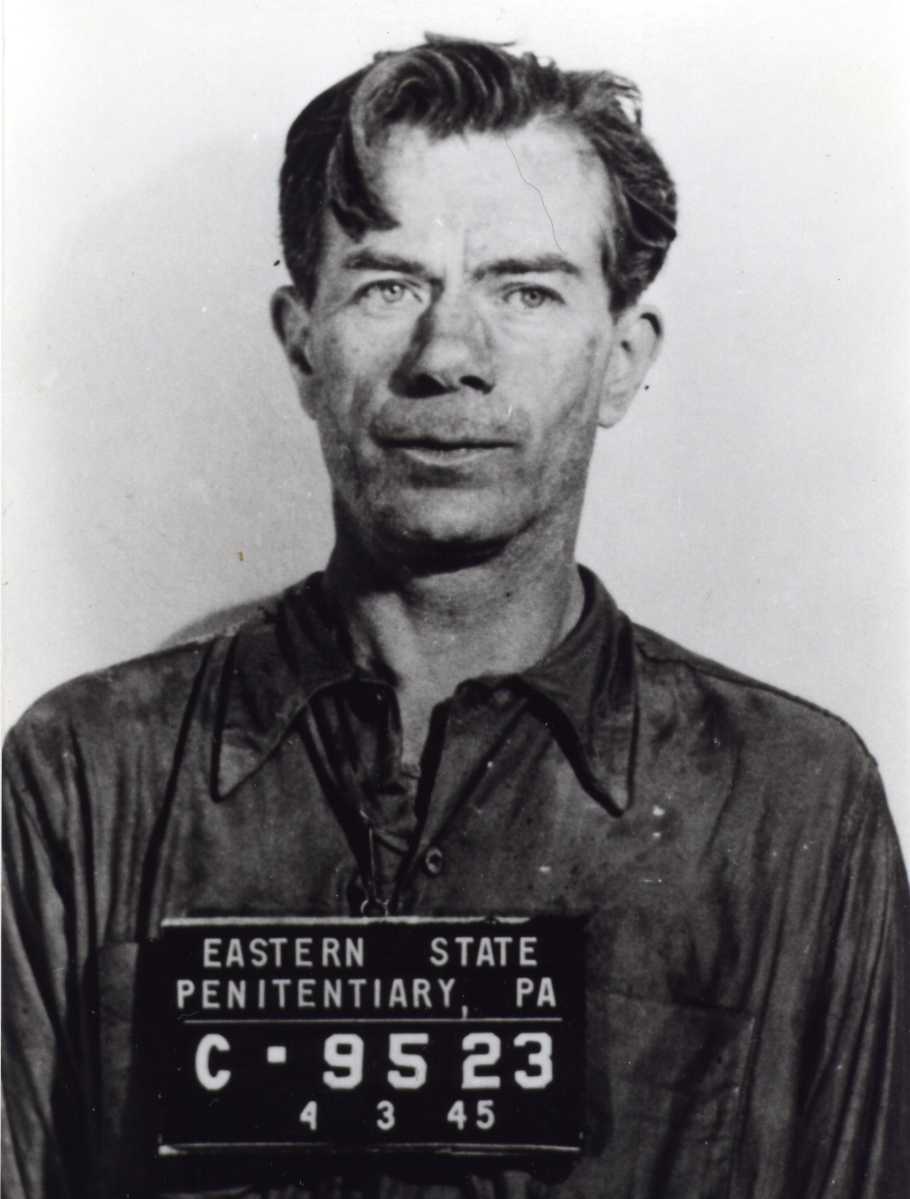

Seventy-five years ago this morning, bank robber Willie Sutton and four other cons scaled the thick, stone walls of Holmesburg Prison in a blinding snowstorm. Lashing two ladders together with rope made of mop strands, they pulled off the first jailbreak since the 35-foot walls were completed in 1894.

After nabbing two guards and forcing them to hand over their uniforms, the escapees set up their ladder. When a tower guard shined a searchlight on them, Sutton, wearing a guard’s coat, hollered, “It’s all right. It’s an emergency!”

Whether the guards didn’t shoot because they couldn’t see through the snow or whether they believed the cons had a captive guard, all five prisoners made it to freedom. Commandeering a milk truck, they grabbed five bottles of milk and toasted their escape as they sped away. When the driver griped his boss would dock him for the milk, Sutton passed him a $5 bill.

The Philadelphia Inquirer dubbed the five veteran jailbreakers “troublesome, truculent badmen.” One was David Aiken, who had become Philadelphia’s first car thief in 1913.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover fumed over the headline-garnering escape and Sutton’s swelling popularity.

Even Sutton didn’t understand his new status as a folk hero. “Hell, I was a professional thief. I wasn’t trying to make the world better for anybody except myself,” he wrote later.

Hoover placed Sutton on the bureau’s new Ten Most Wanted Fugitives List – along with a kidnapper, a murderer, a mail-train robber, a member of the Barker Gang and a man who stuffed his strangled wife’s body into a steamer trunk.

Sutton hitchhiked back to his native Brooklyn, New York and managed to live undetected around the corner from a police station there for five years. On St. Patrick’s Day 1949, Sutton stood on Fifth Avenue, watching the parade from the sidelines.

After he underwent plastic surgery to make his nose less recognizable, Sutton and a pal walked into a post office to view his wanted poster and determine how different he looked.

Wanted posters were routinely mailed to police stations and post offices, but, because Sutton was a meticulous dresser, his also went to clothing stores. Arnold Schuster, a 23-year-old suit salesman, pored over the posters mailed to his father’s shop, so, when he spotted Sutton on a downtown subway in 1952, he recognized him. Schuster flagged down two policemen, the first step in pinching Sutton after five years on the lam.

The patrolmen interviewed Sutton briefly, but he said his name was Charles Gordon, and he had a car registration to match. When a suspicious detective heard the story, he instructed the officers to bring Gordon to the police station. Sutton had a .32 automatic lying in a holster against his stomach, but he kept up the Charles Gordon charade at the station until the fingerprint man said, “That’s Sutton.” Without drama, Sutton said, “You’re right.”

Detective Louis Weiner told reporters Sutton was the nicest crook he ever locked up.

The police held a press conference crowing about the arrest, but forgetting Schuster, who fancied himself an amateur detective and wanted the rumored large reward for nabbing Sutton.

It turned out there was no reward, but the apologetic police quickly acknowledged Schuster’s central role in the manhunt. It didn’t turn out as Schuster had hoped.

At 9:10 p.m. the next Saturday, when families at home were listening to the radio program Gangbusters report on Sutton’s capture, Schuster stepped off a crosstown bus and was shot to death in front of his house. The assailant shot him twice the groin and drilled a bullet through each eye.

Photographers captured a horrific scene – the impeccably dressed young tipster, wearing a suit and fine topcoat, sprawled on the sidewalk with holes where his eyes were and his blood trickling down the cement.

Sutton was grief stricken. He didn’t like being associated with shooting people. He tried to add $10,000 of his savings to the ballooning reward pool for Schuster’s killer, but police persuaded him it wouldn’t look right.

The Schuster case went cold until 1968 when wiseguy Joe Valachi revealed mob boss Albert Anastasia ordered the hit. Anastasia, who had no connection to Sutton, was watching TV when he saw Schuster accept kudos for Sutton’s capture. Valachi said Anastasia suddenly ordered, “ I can’t stand squealers. Hit that guy.”

Sutton was jailed. His sentence was commuted for good behavior and bad health in 1969.

In a 1976 book, he wrote, “I had heard many things about Philadelphia when I was a kid, none of them good.”

Kathryn Canavan is the author of ‘True Crime Philadelphia,’ a new true crime history, including America’s first kidnapping in Germantown in 1874 and the city’s most sensational bank robbery in Olney in 1926.