Bike-share systems in places like New York and Philadelphia are thriving, but a crisis hit—and then sunk—Seattle’s system this month. The Emerald City’s bike-share system is dead. It’s probably got a lot to do with helmet laws. And if we expect Philadelphia’s system to continue expanding, it’s important we don’t ever fall for a false sense of security the way that city did.

After launching in 2014 under the ownership of a nonprofit organization, Seattle’s Pronto Bike Share was bought out by the city for just $1.4 million in 2016.

Being run by the city put Seattle on equal footing with most city bike-share systems in the United States, but the infusion of new leadership and money was not be enough to fix Seattle’s Pronto Bike Share. The city itself is at a disadvantage due to outdated laws that force all cyclists, regardless of age, to wear a helmet.

Helmets Work. Helmet Laws Don’t

The conventional wisdom goes thatbicyclists who ride on the streets with several-ton motor vehicles on a daily basis should be forced to wear helmets if they want to survive a crash. But conventional wisdom is probably wrong.

Wearing a helmet is a good idea, sure. But evidence and data suggest that requiring bicyclists to wear helmets could actually put everyone on the street—bicyclists, pedestrians, and motor vehicle users—inmoredanger. The main argument for helmet usage has been that in the event of a crash, the plastic hat can keep your skull, and brain, safer. And while helmets are shown to work in some cases, required helmet usage could actually make the streets much worse for cyclists.

Helmet Requirements Deter Cycling

Cyclists would be smart to strap on a helmet before riding on the streets with motor vehicles. But required use of helmets creates the guise that cycling is inherently dangerous, and keeps many potentially new users from getting on a bike for the first time.

When new potential mandatory helmet laws for all cyclists are brought up in city halls and state houses around the country, most cycling advocacy groups, who are usually proponents to increases in cyclists’ safety, fight against those laws. They often point to Australia as an example of what can happen when helmets are required by law.

The Aussies have had mandatory helmet laws in place since 1985. Since then, cycling has fallen 37.5 percent and the population has grown at three times the growth of cycling. The helmet requirements have additionally been blamed for that country’s abysmal bike-share systems.

Additionally, the unintended consequences of helmet laws are staggering.

“Pushing helmets really kills cycling and bike-sharing in particular because it promotes a sense of danger that just isn’t justified—in fact, cycling has many health benefits,” Piet de Jong, a professor in the department of applied finance and actuarial studies at Macquarie University in Sydney, told the New York Times in 2013.

Part of the reason Seattle’s Pronto Bike Share had such a tumultuous life and death is the deterrent of the required helmet. Each bike share station in Seattle was accompanied by a helmet kiosk, which for an extra $2, provided users with helmets for their trip. That doesn’t seem too steep, until you think about the point of bike-share systems: It’s mostly for riding a mile or two, not taking to the trails for the day.

All that aside, the helmets ate away at Pronto Bike Share’s potential profits. Those helmets needed to be picked up by staff members, cleaned, and re-stocked, along with the bikes themselves, which added tens of thousands to the annual budget, according to local media.

“Getting a helmet from the bin adds a step to and otherwise streamlined process, and are you really going to unwrap and ‘dirty’ a helmet just to bike a mile or so?” asked Tom Fuccoloro, of Seattle Bike Blog. “The added cost of a helmet further deters low-income users or exposes them to citations for choosing not to wear a helmet, an act that is perfectly legal in nearly every other big city in the nation and the world.”

Helmet laws deter spontaneous riding. If your train is delayed for some reason, jumping on bike-share should be a viable option. But it probably wouldn’t be if you knew you could get a ticket for riding without a helmet. And how many people pack a helmet “just in case?”

More Cycling Is The Key To Safer Cities

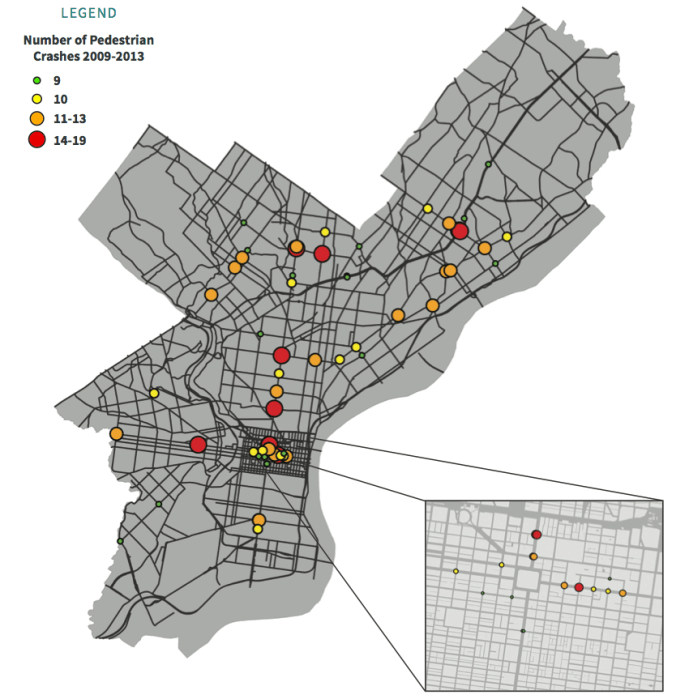

Studies have shown, again and again, that cyclists experience safety in numbers. Essentially, the more cyclists there are on the road in a given area, the more likely drivers are to pay attention to the road for fear of hitting a cyclist. The Alliance for Biking and Walking, conducting its own research and citing government data, analyzed bicycling in 52 cities in 2014 and found that cities with the highest bicycling rates most often had the lowest rates of crashes and fatalities.

So, go ahead: wear a helmet. I do. Let’s just make sure to never make it the law.

Randy LoBasso is communications manager at the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia.