By Miguel Velázquez, MWN

The novel coronavirus has changed everyday lives in countless ways, but perhaps none more impactful then the way we educate children.

The global health emergency had a great impact on the education of millions. In April 2020, a month when the strictest lockdown measures were implemented in many countries, nearly 90 percent of students had their learning processes disrupted. According to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), as of Dec. 1, 2020, schools remained closed for one in five school-age children worldwide, a total of 320 million children.

In-person classes were replaced by virtual ones in many cases, however, it turned out to be quite challenging. Two-thirds of the world’s school-age people – or 1.3 billion children aged 3 to 17 years old – do not have Internet connection in their homes, according to a new joint report from UNICEF and the International Telecommunication Union.

“As we enter the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, and as cases continue to soar around the world, no effort should be spared to keep schools open or prioritize them in reopening plans,” Henrietta Fore, UNICEF Executive Director, said in a statement.

She added: “The cost of closing schools has been devastating. The number of out-of-school children is set to increase by 24 million, to a level we have not seen in years and have fought so hard to overcome.”

According to UNICEF Executive Director, children’s ability to read, write and do basic math has suffered, “and the skills they need to thrive in the 21st-century economy have diminished.”

Nearly a quarter of a billion students worldwide are still affected by COVID-19 school closures, forcing hundreds of millions of students to rely on virtual learning, explains Fore, warning that “for those with no Internet access, education can be out of reach.”

Indeed, the digital divide is perpetuating inequalities that already divide countries and communities. Children and young people from the poorest households, rural and lower-income states are falling even further behind their peers and are left with very little opportunity to ever catch up.

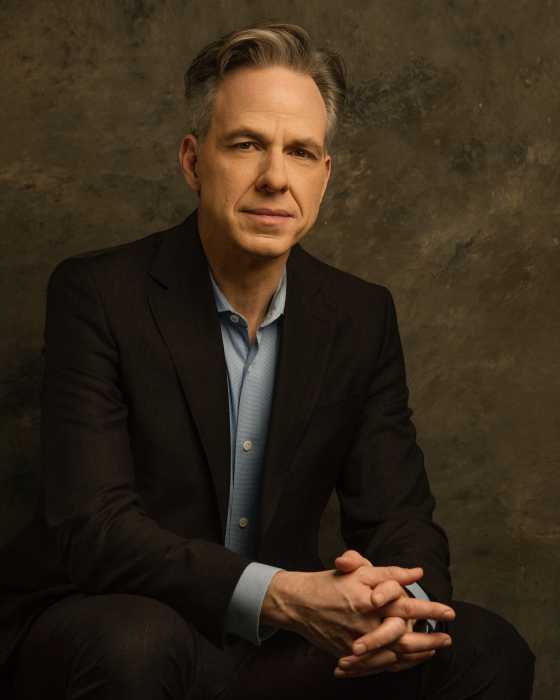

To learn more about the situation, Metro talked with Glenn C. Savage, associate professor in education policy and sociology at The University of Western Australia.

Was 2020 a lost year for education?

From a global perspective, the answer would be both yes and no, depending on where young people attend school. For many students, 2020 was a terrible year for the progression of their learning. There is deeply worrying data globally showing the negative academic impacts the pandemic has had on young people’s achievements. These impacts are strongly influenced by socio-economic factors, with young people from disadvantaged backgrounds more likely to have been negatively impacted.

The impacts are also very different when we compare nations. In Australia, young people were only away from face-to-face schooling for a relatively short period, and the shift to online learning was in many cases successful. In other nations, young people have spent extended periods away from schools and education systems have struggled to move effectively online.

Is it possible to measure the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic had on global education?

Measuring the impact of the pandemic on academic achievement is complicated, but easier to do when compared to measuring the impact on other areas of student development. For example, a crucial element of the pandemic that has not received the attention it deserves to date is considering what is lost when schools, as primary sites for the socialization of young people, stop operating face-to-face. These social dimensions of schooling include young people’s relationships with others, their development as future citizens and much more. How do we measure these dimensions? It is much harder.

For me, the pandemic has reinforced a view that schools are not just factories for the transmission of academic knowledge, nor are they simply hothouses for the crafting of future participants in national and global economies. Schools are, instead, where our future citizens are—future citizens who need schools to help them navigate social worlds. When we mourn what is being lost to the pandemic in education, we should be mourning the social life of schools.

How effective is online schooling?

When we compare online learning across education systems globally, there are deeply concerning differences in terms of how effective the online shift has been. Many systems simply did not have the technical infrastructure in place to suddenly move large numbers of young people online. Many teachers lack adequate training in online teaching. And many young people live in households that lack access to high-speed Internet and the devices required to engage in online education. At the other end of the spectrum, some education systems were very well placed to make the move online.