On a warm night back in June, Michael Horowitz was walking through Dilworth Park. It was a beautiful night. He had just had dinner with his wife. There were children playing in the fountains.

Then he heard a crash, and he saw a scene that boggled his mind.

A man on a bike had ridden through the fountains where those kids were playing.

The cyclist hit one of them.

How crowded was it?

“If you were riding a bike through a group of children like that, you could maybe avoid hitting one if they were all stationary,” said Horowitz, 30.

The bike the rider was on was from Indego, the sharing service that allows people to rent bikes for short periods of time.

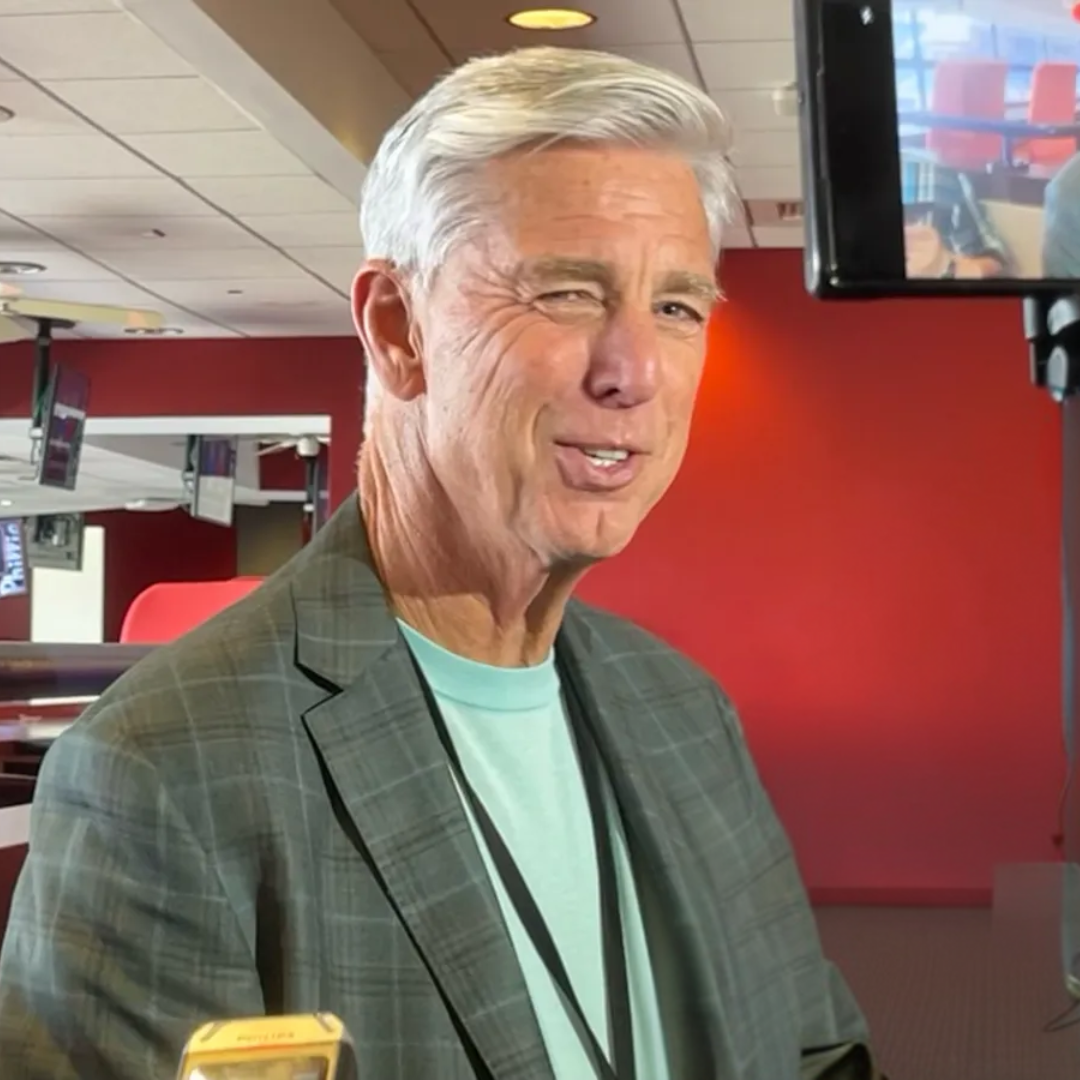

Over the past few weeks, the service has come under some criticism over small, but persistent concerns that it has put cyclists on the street who have little to no experience riding bikes in the city. A writer for Phillymag noted that “people who hop on bikes after years of not using one and head straight to traffic-packed city streets have the potential to give all city bikers a bad name,” after watching an Indego cyclist careen through a crosswalk crowded with pedestriansand through an intersection. And just last week, Philadelphia’s cycling community began collectively breathing into paper bags after a video hit the internet featuring two Indego riders who somehow ended up on I-676. Denise Goren, the director of policy and planning for the Mayor’s Office of Transportation and Utilities says one reason for the bad rap is because Indego bikes are so obvious. Everyone knows when a rider is on one. She says that out of more than 100,00 rides taken by users on Indego, the system has seen just three crashes. She did not have information available about the experience level of riders who use it. Randy LoBasso, a spokesman for the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia points out that tracking of bicycle-collisions isn’t comprehensive. People tend not to get hurt, so whether they are on Indego or not, bike crashes tend not to get reported to police. “In general, bike sharing brings more people to the street,” LoBasso said, “and that makes the streets safer.”

It doesn’t appear that the crash Horowitzwitnessed was reported to Indego.

Horowitz, who is an avid cyclist who has used Indego,says the boy was transported to a hospital by paramedics — he had a cut on his face and was limping a bit. The Indego rider fled the scene. Goren says the service works hard to promote safety. There are safety warnings on the bikes and on the station where riders pick them up. They tweet safety messages two or three times per day.

Prior to watching the aftermath of the bike in the fountain accident, Horowitzbelieved that Indego riders were less experienced, and more likely to ride on the sidewalk or the wrong way down one-way streets. But since the accident, he says he’s been paying more attention, and he agrees with Goren’s assessment that Indego riders seem more dangerous because they stick out.

“I see cyclists break the law all the time, and I see cyclists obey the law all the time,” Horowitz said.

Are Indego riders more dangerous than regular cyclists?

The new Indego bike share service has flooded the streets with bikers and bike-sharers.

Charles Mostoller