“Cheyneyis on fire. We need some firemen andfirewomento go put it out.”

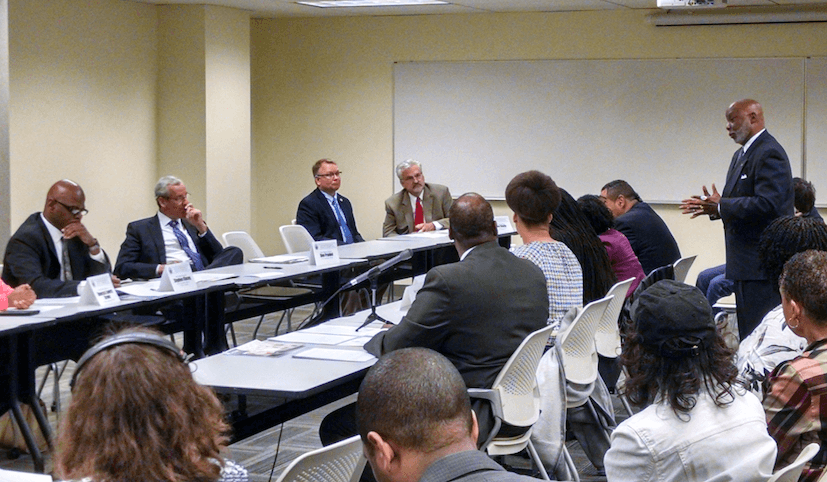

WIth those words, late professor Sonny Harris in 2013 founded HeedingCheyney’sCall, a group of alumni working to resolve funding woes at Cheyney University, the oldest historically black college or university in the country. The school, which is 30 miles from Center City, was founded in 1837. Despite their efforts, Cheyney is still in straits so dire they could be fatal, with a shrinking student body and mounting debts, alumni and current students testified ata hearing of the state House Democrats Tuesday held inPhiladelphiaon restabilizing Cheyney’sfinances. Cheyney’sfinances have been battered bydwindling enrollment, which was at 711 in fall of 2015, down from 1,488 in2008. The six-year graduation rate is about 27 percent.

Attorney Michael CoarddescribedCheyneyas “an all-time great university with all-time low student enrollment and an all-time high budget deficit” at the hearing.

His message to the elected officials?

“Stop doing the bad stuff you’ve been doing toCheyneyall along,”Coardtold the panel of 15 Democrats. “IfCheyneyhad been treated like the other 13 [state schools] since the beginning, we wouldn’t even be here.” Cheyneyisone of the 14 state colleges operated by Pennsylvania’s State System of Higher Education. In recent years,the school has fallen on hard times financially, leading alumni from Heeding Cheyney’s Call to file a civil rights lawsuit for “parity through equity,” arguing that the school was being racially discriminated against due to a lack of funding. Funding has been a problem for historically black colleges nationwide, which after decades of underfunding have difficulty attracting students to aged campuses without some of the degree programs and amenities students can find elsewhere. Last year,South Carolina State University, the state’s only public historically black college, narrowly dodged closureafter falling deeply into debt from dwindling enrollment. The federal government found in 1969 that Pennsylvanvia historically operated a segregated higher education system. Complaints included contractors cutting corners and using the cheapest possible materials while building Cheyney’s campus. A 1999 agreement with the federal Office of Civil Rights required PASSHE to boost support for Cheyney to alleviate the effects of thathistoric racism. The civil rights lawsuit over funding Cheyney was put on hiatus after the alumni entered negotiations with Gov. Tom Wolf in 2015, and was dismissed without prejudice in January. Wolf has assured alumni he is “committed to savingCheyneybut also to enhancingCheyney,” according to the alumni group. Now they are back to the negotiating table, as Coardput it. Cheyney, which has an open admissions policy,was described at the hearing as a school that offers students “second chances,” and has led many African American students to success. Past alumni include RobertBogle, CEO of the Philadelphia Tribune newspaper, civil rights activistOctaviusCatto, and playwright Levy Lee Simon. But current Cheyneystudentsat the hearing described departments with outdated technology, facilities with moldy smells, poor food options and other issues that make the university less desirable to students. “To a great extent, we have many of the pieces in place, but it’s just not coming together,” said Robert Wright Sr., director of the William Penn School District board. “A lot of it has to do with funding.” The school seems to be locked in a vicious cycle, as the declining quality of faciilities and on-campus resources make the school less attractive to students in comparison with other state schools, which have the same tuition costs. At Cheyney, the school may be required to repay $30 million in federal aid due to failing to properly track it.Meanwhile, the school’s deficit is estimated to reach $19 million by the end of June, and PASSHE has loaned the school about $13 million over the last 18 months to help cover their operating cost. Since 2005, it has received $104 million in capital funds for facilities and construction improvements from the state, about twice the systemwide average of $54 million, according to PASSHE. There are some out-of-the-box ideas for how to lift Cheyney’s fortunes.Cheyneyalum Allen Smith argued at the hearing that federal tax credits for community development could be tapped to rebuildCheyneyin Philly as an urban school, leaving Lincoln University, another localhistorically black college, as thesuburban alternative, while Cheyney’s campus could be sold off or merged with nearby West Chester University. Representatives of PASSHE attended the hearing but did not testify.

“We continue to work with the leadership of Cheyney University, including the Council of Trustees, and the Commonwealth, including the Legislature, with the goal of helping to preserve the long-term future of the institution,” PASSHE spokesman Kenn Marshall said in a statement. State representatives at the hearing said they will seek to hold another hearing of the full House on the issue of Cheyney’s funding.In the meantime, Cheyney’scurrent students are still proud of their school. “We do have a hard time, but it’s going to be a better day forCheyney,” saidNyrieWatson, 20, a specialeducation major from Wilmington,Delaware. “If the campus was bustling with students before, it can again.”