Before he was evicted, Mark Person thought he and his landlord could work out what he described as a dispute over the timing of an exterminator visit.

Then, one day in February, he heard from neighbors that a deputy landlord-tenant officer was in his apartment building. Person heard a knock at his door, and the officer told him he had 10 minutes to grab what he could and vacate the property.

“There was no notice or courtesy, just him standing with his hand atop his pistol like a cowboy in a Western,” Person told City Council members Wednesday during a hearing examining the role of Philadelphia’s landlord-tenant officer.

Appointed by the head municipal court judge, the officer is a private attorney who is paid to carry out evictions.

The position has come under increased scrutiny since a deputy landlord-tenant officer shot 35-year-old Angel Davis in the head March 29 while attempting to remove her from her North Philadelphia apartment. Davis survived but suffered severe injuries.

In response to Davis’s shooting, state Sen. Nikil Saval has introduced a bill prohibiting cities from hiring private entities to enforce eviction orders. Local judicial leaders have also been meeting in recent weeks to discuss possible reforms.

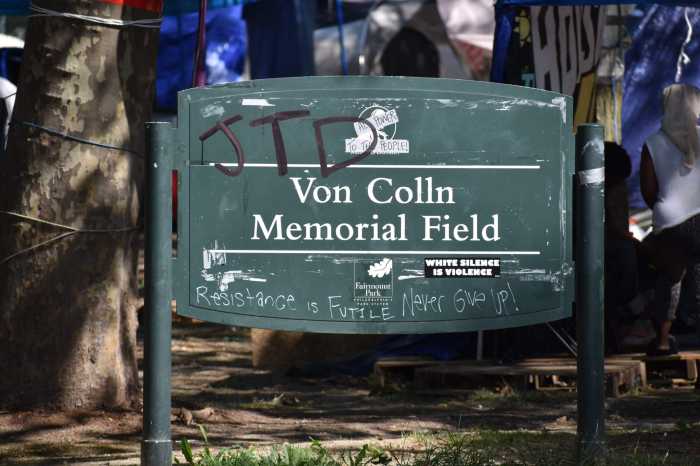

City Councilmember Jamie Gauthier said that, after spending the past few months studying the eviction process, she determined that it is “a violent, traumatic and dangerous system that demands reform.”

During Wednesday’s hearing, legal service providers, renters and tenant advocates described the stress of experience, particularly highlighting the office’s policy of not providing a timeframe for lockouts.

Marisa Shuter, the current landlord-tenant officer, did not respond to a request for comment.

Evictions in Philadelphia begin with a 10-day notice to vacate. Once that period is up, property owners can file a complaint in court after participating in a mediation program established during the coronavirus pandemic. Renters are supposed to be alerted to the proceedings, though some reported being unaware of the case.

A hearing is scheduled, and, if either side does not show, the judge issues a default decision in favor of whoever showed up. A 2018 Kenney administration report found that more than half of landlord-tenant cases ended with a default judgment against the tenant.

Following the hearing, the landlord can apply for a writ of possession, allowing them to reclaim the unit. They must wait at least three weeks from the judge’s decision to enforce the eviction, but there is no specific deadline for them to act.

Then, a landlord-tenant officer or, less frequently, a sheriff’s deputy arrives without prior warning to remove the renter. If the person is not home, the property owner can have the locks changed without allowing the tenant to retrieve their belongings.

“Most tenants who have shared their experiences with us have expressed they get approximately 10 to 15 minutes to vacate the property with everything they need,” said Sherry Thomas, director of housing for the Legal Clinic for the Disabled.

Thomas added that the short notice is especially difficult for people with disabilities and older residents, who often have to pack up multiple prescriptions and medical equipment.

Several who testified at the hearing spoke of having to leave cats and other pets behind.

Tenants often remain until the eviction because they may not be aware of the process or have no place else to go, said Councilmember Kendra Brooks, who has also been researching the system.

The landlord-tenant office, lawmakers and advocates said, has no publicly available policies or formal training procedures for deputies.

In contrast, constables in Allegheny County are expected to follow a 77-page handbook. Most Pennsylvania counties use constables for evictions. Philadelphia did until 1970, when city leaders adopted the current arrangement.

Kyle Webster, of Action Housing, a nonprofit developer in the Pittsburgh area, told lawmakers that notices in Allegheny County typically include the date on which the locks will be changed.

New York deploys city marshals, who must execute an eviction within a month of the writ of possession, said Nikita Salehi Azhan, of Mobilization for Justice, a legal services organization. She added that tenants subject to removal can call the day before to find out when they will be evicted.

“This short notice that is available to the tenants has been shown to have no adverse impact on the city marshal safety,” Salehi Azhan said at the hearing.

One option is to shift all eviction proceedings to the sheriff’s office. Andrew Del Valle, vice president of government affairs for the Pennsylvania Apartment Association, said landlords are concerned that could lead to “potential increased costs, process delays and other challenges.”

Philadelphia judicial leadership has been meeting with stakeholders in recent weeks to discuss the future of the landlord-tenant officer.

“Our hope is that meaningful progress can be achieved in the next several months,” said Marc Zucker, chancellor of the Philadelphia Bar Association, which has facilitated the talks.