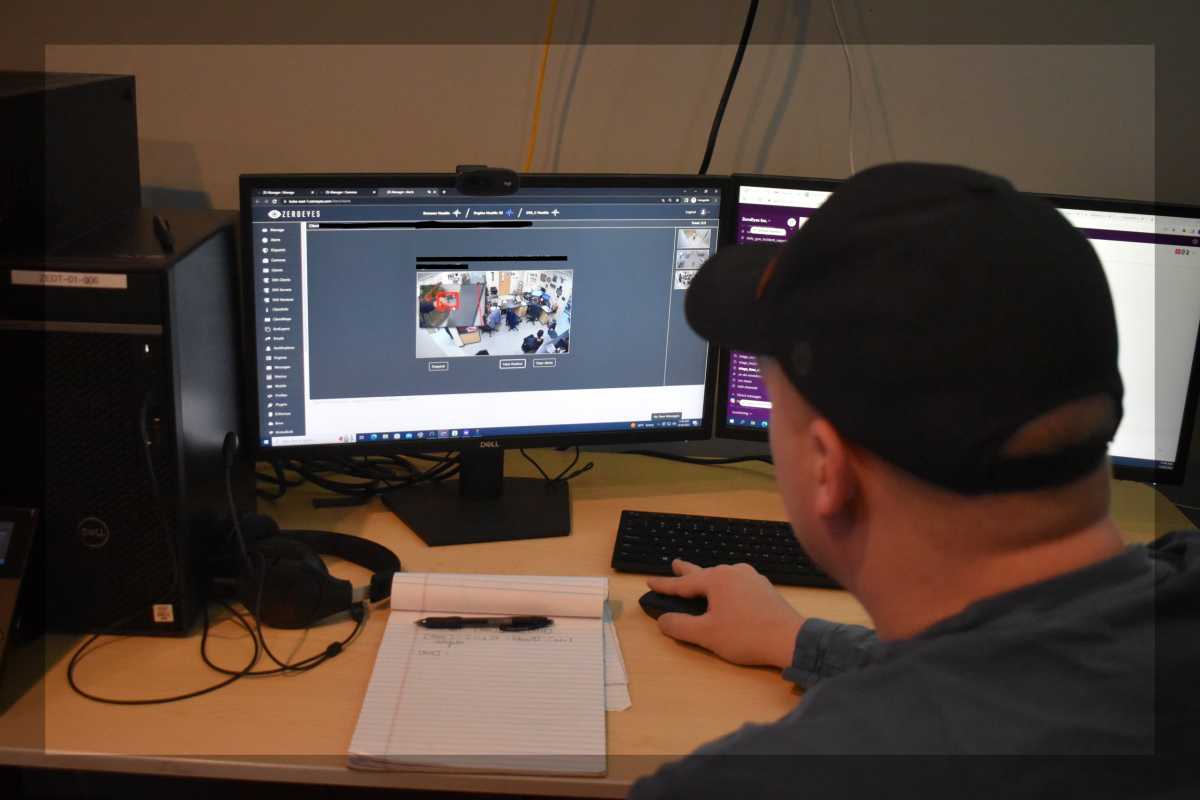

Jared Klentz sat in front of a computer on a recent weekday morning in a small, screen-filled room in Conshohocken’s sprawling Spring Mill complex.

He works for ZeroEyes, and he was waiting for screenshots from security cameras to appear on his monitor. When an image popped up, Klentz hovered his cursor over a red box to magnify an object identified as a possible firearm by artificial intelligence.

ZeroEyes, founded in Philadelphia and now based in the suburbs, uses an algorithm to spot guns caught on a school, casino or corporate office’s existing security camera system. If confirmed by a human, like Klentz, law enforcement is dispatched to the location.

The company’s founders believe their technology can prevent mass shootings – and could have led to the apprehensions of gunmen before they shot up schools in Uvalde, Texas, and Parkland, Florida.

A newer client is SEPTA, which is expected to implement ZeroEyes’s system next month on the Broad Street and Market-Frankford lines as part of a pilot program.

Down the road from Spring Mill, the start-up has a green screen studio, where employees choose from a catalog of different firearms, shirts, gloves and lighting conditions to simulate active shooter situations, explains ZeroEyes co-founder and chief revenue officer Sam Alaimo.

The backgrounds range from the gaming floor of a casino – complete with swirling carpet and slot machines – to an outdoor plaza outside a skyscraper. ZeroEyes’s aim is for the AI to learn to recognize guns in any setting.

“We didn’t scrape the web like a lot of AI companies, which means Google pictures of guns, save them and put them through the algorithm,” Alaimo told Metro. “We create our own images.”

If the algorithm finds a weapon, Klentz and others in the Conshohocken operations center are notified. The firm also has a ZeroEyes Operations Center – or ZOC – in Honolulu, Hawaii, to cater to time zone differences.

ZOC employees, who are typically ex-military or -law enforcement, can notify police, flag the alert as a false alarm, or let their client know of a non-lethal threat, such as a student pointing a cellphone like a gun in the hallways.

ZeroEyes, in the case of an active shooter, can provide a description to first responders and produce an overlay of the facility in question, creating a breadcrumb trail showing where the suspect has been.

Prior to the Uvalde shooting, which left 21 people dead, the shooter, Salvador Ramos, crashed a vehicle near the school and opened fire outside before entering the building with an assault rifle.

“We would have had that gun without question outside of that building,” Alaimo told Metro, adding that many mass shooters stalk the area with their firearms out before attacking.

The company was formed four years ago by a group of former U.S. Navy SEALs, including CEO Mike Lahiff, who previously was employed as an executive at Comcast. Alaimo said around 70% of the ZeroEyes workforce are military veterans.

Lahiff, in the wake of the Parkland shooting, asked security staff at his daughter’s school who was monitoring their cameras, and he was told there was no real-time component, Alaimo relayed. The footage was only checked after an incident.

ZeroEyes provides few specifics about its clients, except to say the technology is being used in 30 states and three countries. The firm focuses on three sectors: commercial, education and government.

Details about the cost are also sparse, though Alaimo said the company typically provides multiple quotes at different price points.

In November, SEPTA became the first major transit system to sign an agreement with ZeroEyes, approving a $63,000 contract for a six-month pilot program deploying the algorithm to a small fraction of the authority’s 30,000 cameras.

The pilot is set to be significantly expanded – before it even begins – thanks to a $4.9 million state public safety grant announced earlier this month.

In a recent Inquirer op-ed, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania warned SEPTA of possible racial profiling in AI technology and suggested several steps to mitigate bias.

Alaimo and other ZeroEyes staff said they are careful to weed out false positives because they know reporting an active shooter escalates a situation for everyone involved.

The company, unlike others in the field, does not do facial recognition, track live video or save data, Alaimo said. Rather, Zeroeyes focuses solely on detecting guns before shots are fired.

“We want to focus on gun detection and be the best in the world at that, and we are,” he added.