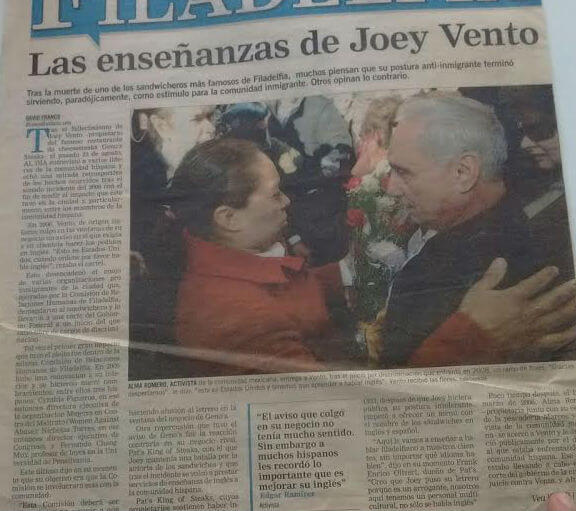

On one side of South Ninth Street, the rioters gathered. They shouted and banged their drums and thrust their fists in solidarity. On the opposite side, a band of supporters waved American flags and shouted anti-immigration rhetoric, all in defense of a controversial sign at Geno’s. That was 2006. Last week, a sign put up by owner Joey Vento instructing customers to “speak English” when ordering finally came down, but an element of trauma still lingers in the diverse Italian Market community. Alma Romero was one of those protesters. Ten years later, she still won’t go to Geno’s.

“Para nada, para nada,” Romero said. Never, never.

“The owner was very aggressive. We didn’t want to be like him, so we protested passively, not being aggressive,” said Romero, who has lived in South Philly for 17 years.

At the time, Latinos in the neighborhood devised a plan: They would go to Geno’s, order in Spanish and see what happened. Romero went with her sister, and they asked for abistec.

“They ignored us,” Romero recalled.

When Vento hung his sign, which read “This is AMERICA, when ordering, speak English,” he insisted the shopwouldn’t turn away any customers. It was that argument that allowed Vento to keep displaying the sign, even after a 21-month fightwith the Philadelphia Commission on Human Relationsover concerns about possiblediscrimination. Romero said that sign fractured their neighborhood, which was looking far less Italian than it once did. From 1996 to the present, an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 Latino immigrants moved into Philadelphia, many flocking to the Italian Market to grow businesses and raise families. These new residents feared Vento. After the sign went up, they feared he’d call immigration while they played with their children in the park across the street, Romero said. Suddenly, his rival, Pat’s King of Steaks, had an influx of loyal customers. “Since [that protest], there have been a lot of people who say, ‘You don’t go to Geno’s, you go to Pat’s,because Geno’s is clearly not about our community,'”Erika Almiron, executive director of nonprofit immigration advocacy group Juntos said. “This had very little to do with foreign visitors, and had more to do with the changing demographics of that neighborhood,” saidMayor Jim Kenney, who was Councilman Kenney when Vento posted the placard. “When you go back to some of Joe’s magazine comments…this guy was not progressive at all. In fact, he was pretty much racist.” Vento died five years ago. His son and successor Geno Vento has said it was his father’sdying wish to keep that sign up. But just before the Democratic National Convention, Genoquietly removed the contentioussignso as to not make any visitors feel unwelcome. “I didn’t know that, and it feels really bad,” said Romero, who owns a business in the Italian Market. “We’re here, and we’re his people. We’re the people of this neighborhood…Even if they haven’t changed the name of the Italian Market, it is also dominated by a lot of Mexican and Latino businesses.” “I’ll always see it as being anti-immigrant,” Romero said. “Even after [Vento] passed away, they kept that sign up. That says a lot.”

An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified Alma Romero as Alma Rodriguez.