Overbrook’s Muhammad Sayyid and his wife Samira, who both asked that their real names not be used for this story, are people of faith who pray toward Mecca fives times a day and pay their rent on time every month.

The apartment complex where they live, a four-story building called “the Jefferson,” located at 63rd and Jefferson streets, is about a 10-minute bike ride from St. Joseph’s University and offers residents a clear view of the Center City skyline. In a majority Black neighborhood where poverty rates increased almost 7% since 2014, the Jefferson, though not without problems typical of any apartment building, offered those who live there stable, well-maintained housing at an affordable price.

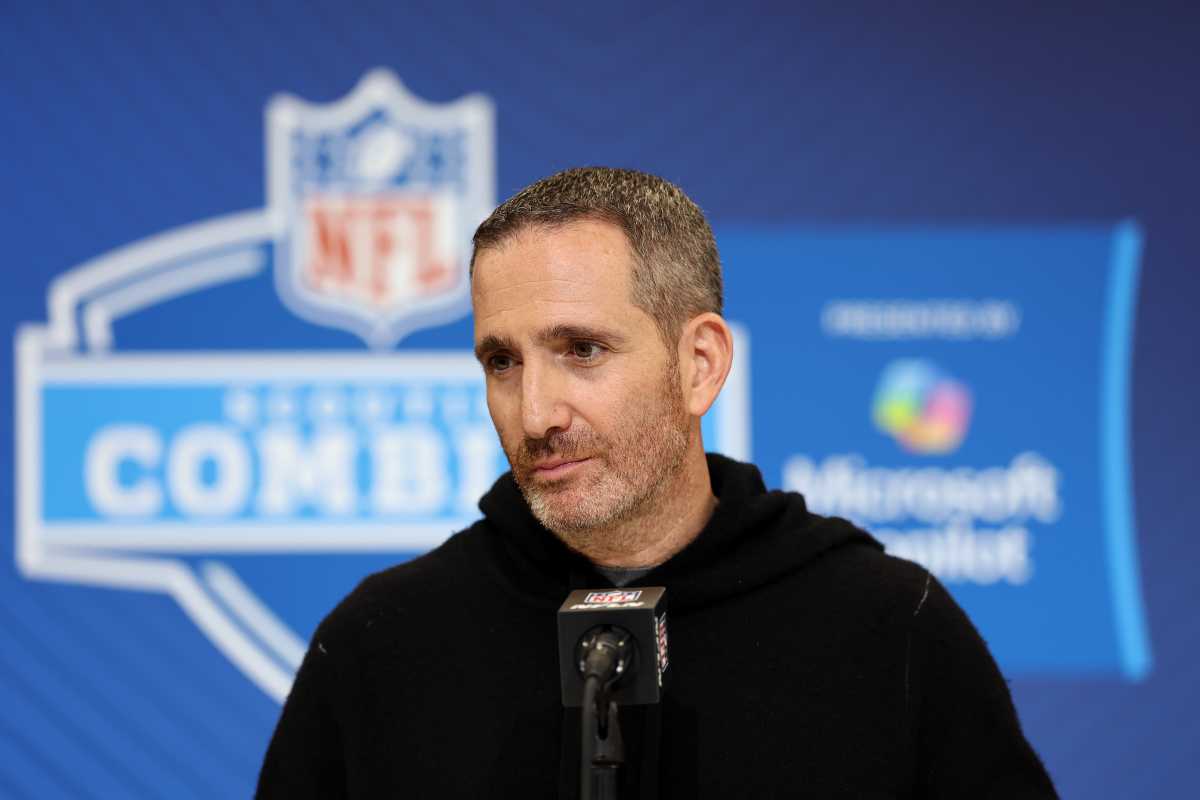

But last summer, as the Delta variant emerged, residents of the Jefferson learned the building was under new management, and everything changed. In a letter dated June 15, Greenzang Properties’ Steve Reize introduced himself as the building’s new property manager, explaining new procedures for property communication and rental payments while noting email was the preferred contact method. Greenzang Properties and its president, Michael Greenzang, own and operate over 2,000 apartments in the Philadelphia region with a stated acquisition strategy to “buy, improve and hold.”

In the case of the Jefferson, Greenzang’s role is that of a third-party property manager and not a building owner. Still, knowing that did nothing to quash the Sayyids’ and other residents’ anger when, a month later on July 23, a notice came on Greenzang letterhead that new ownership would not renew leases. And, according to several people who live in the apartment, that’s when the real problems began in the building.

“You’ve got to give people a chance to do what they need to do — they’re not even talking to us, they’re not communicating [with] us … no communication, nothing,” Mrs. Sayyid said as her husband nodded in agreement. “And when you ask them to fix things, they can’t even fix a blind. The light in our bathroom is out. The light in the hallway is dimming … we need maintenance to come be able to do that.”

“They make you feel like they just want you out,” both Sayyids said in unison.

Muhammad and Samira Sayyid are among the scores of residents in the almost 100-year-old Jefferson apartments in Overbrook who have lost or are preparing to lose their homes as new ownership seeks to turn over the building for as-yet unconfirmed reasons. Although current city records show the property’s last sale was in 2018, former owners confirmed with the Metro that they sold the building in June of this year, while legal experts in the affordable housing space noted that Philadelphia’s property records might not be up to date.

A party said to represent the building’s new owners, who stated that such persons or organizations wished to remain anonymous, told the Metro that the Jefferson would be transformed into low-income affordable housing once current tenants move out. The Metro was unable to confirm or disprove that information via public records or a second source.

Built in 1924, the Jefferson was part of a trend toward multifamily efficiency dwellings aimed at the middle class of the time, similar to other buildings such as the Overbrook Gardens, the Overbrook Arms and the Anita Apartments, among others.

Although new owners say they will erect affordable housing on the site — and there is no evidence to suggest otherwise right now — the Jefferson does sit in a neighborhood overrun by gentrification projects over the past few years. Developers continue to push people out of buildings in Overbrook, which falls under the purview of Councilperson Curtis Jones Jr., including Penn Wynn House, Admiral Court apartments and Dorset Court apartments.

“Gentrification was primarily a South Philadelphia and North Philadelphia issue,” Councilperson Jones said in a statement. “It has now reached my district. Penn Wynn was the first but as we can see today, it will not be the last. We are reaching out to [Tenant Union Representative Network] and [Community Legal Services] to provide assistance to the [Jefferson] residents and we are looking to legislative and budgetary solutions to address this ever-increasing problem.”

There’s little evidence available to help residents of the Jefferson understand their current situation. The currently-listed property owners, as per city records, say they sold the place in June. New owners, who wish to remain anonymous, said they will turn the site into affordable housing, though there are no public records or statements to this effect. The building’s rental license, held by the former ownership, expired on Oct. 31, which experts say means no one has the legal right to collect rent or evict anyone from the building.

Last February, Annette M. Talerico, an employee of Obermayer Rebmann Maxwell & Hippel LLP, a Philadelphia law firm, listed herself as an organizer of a new limited liability corporation, 901 N. 63rd St. LLC, which is the address of the Jefferson. The Metro reached out to both Talerico and Obermayer Law for comment, with no response.

In the meantime, residents of the Jefferson continue to struggle and fight through the stress of losing their homes in the middle of a pandemic. The building is filthy, with trash strewed everywhere. Maintenance requests go unanswered, and the building’s heat remains off, even as the weather grows colder. In the back is a mishmash of loose wires and a broken door that allows anyone to come in and out of the building, leaving residents fearing for their safety. Those who are sick and elderly spend every day wondering if the elevator will work.

For some, there are constant phone calls asking them when they will leave and workers barging into their apartments, invading their privacy.

“The first time somebody actually opened my door and I was upset — I’m like, what are you doing?” Natasha, a mother of two children, said. “He was supposed to be upstairs, fixing one of the units upstairs, but I still felt unsafe. I actually ended up calling the cops because I didn’t know what was going on.”

Tenants don’t have much protection when a landlord decides not to renew a lease. Lobbyists watered down “good cause” laws so that only those on short-term leases have any ability to fight back. But residents can turn to area organizations for help, including Tenant Union Representative Network and Community Legal Services, in times of need.

The Sayyids were able to manage it, but, as they noted, it came at a cost. Three months’ worth of rent was money they saved for years for a trip to Mecca, the holiest of places they have always wanted to visit — a journey that will have to wait a little longer. “If you’ve got a base of tenants, that’s here, that’s paying their rent, why push that out?” Mrs. Sayyid said. “But if you do decide to clear the building out, give people a chance to save the money to get out.”

Metro is one of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on economic mobility. Read more at brokeinphilly.org or follow on Twitter at @BrokeInPhilly.