By MARYCLAIRE DALE Associated Press

Three long-retired Philadelphia police detectives must stand trial, accused of lying under oath at the 2016 retrial of a man the jury exonerated in a 1991 rape and murder.

The case, if it proceeds to trial in November, would mark a rare time when police or prosecutors face criminal charges for alleged misconduct that leads to wrongful convictions. Of the nearly 3,500 people exonerated of serious crimes in the U.S. since 1989, more than half of the cases were marred by allegations of flawed work by police or prosecutors, according to a national database.

Former detectives Martin Devlin, Manuel Santiago, and Frank Jastrzembski, all now in their 70s, hoped a judge would dismiss the case over evidence aired before the grand jury that indicted them.

Defense lawyer Brian McMonagle argued Friday that prosecutors tainted the process by letting jurors hear that the detectives had a long history of “committing perjury … and beating statements out of people.”

Philadelphia Common Pleas Judge Lucretia Clemons acknowledged mistakes in the grand jury room but said there was enough evidence remaining to send the case to trial. However, she may let the defense appeal the grand jury issue to the state Superior Court before trial.

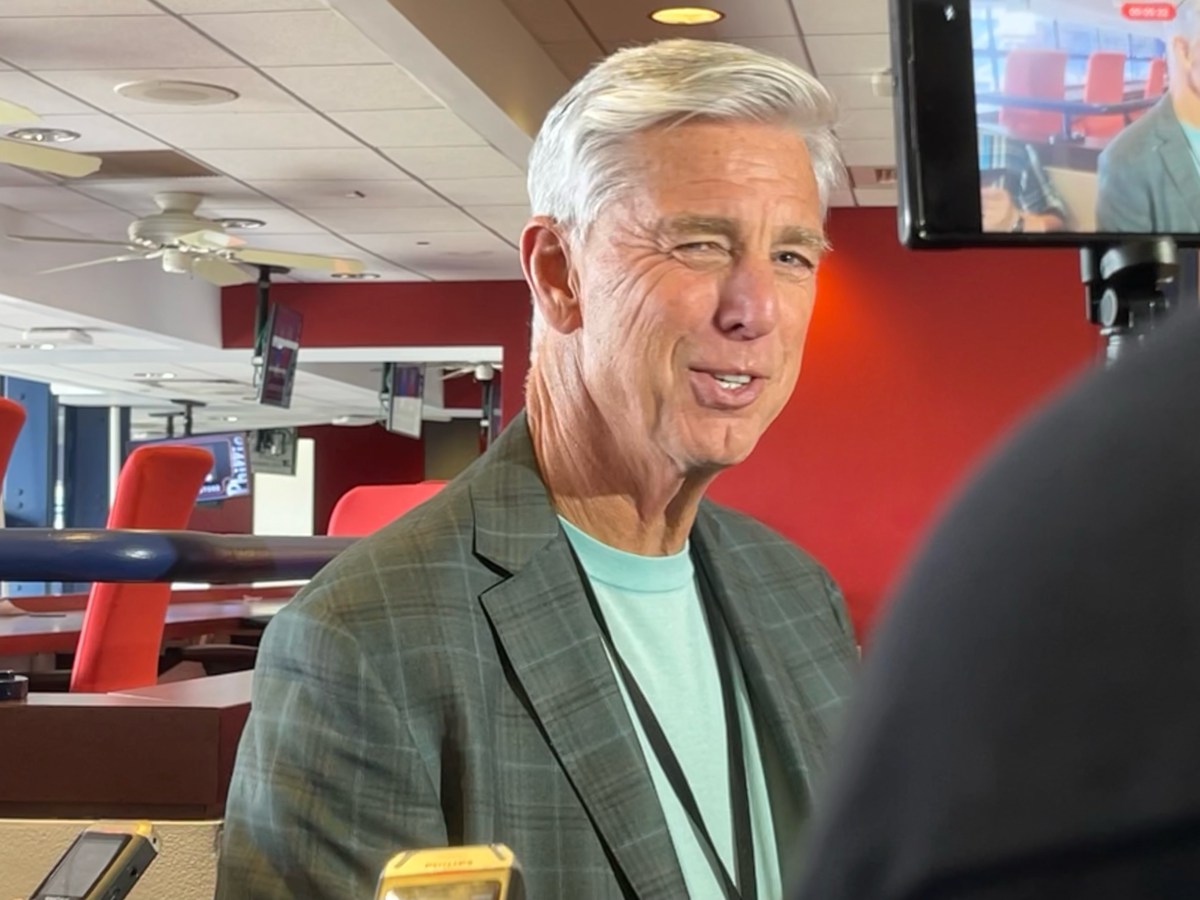

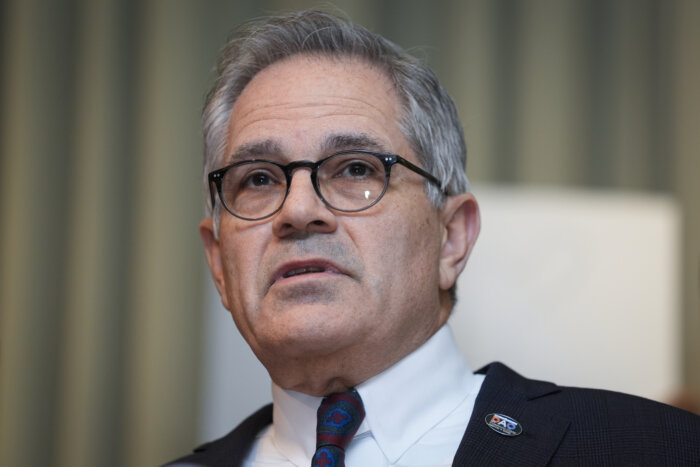

An unusual confluence of factors allowed District Attorney Larry Krasner to charge the detectives in the case of exoneree Anthony Wright, who was convicted in 1993 of an elderly widow’s rape and murder two years earlier.

Wright was arrested at age 20. He spent two decades in prison before DNA testing seemingly cleared him of the crime. Despite the DNA exclusion, Krasner’s predecessor chose to retry him, calling the detectives out of retirement to testify. The five-year window to file perjury charges for trial testimony began anew.

The key piece of evidence remaining at the retrial was Wright’s confession. His lawyers argued that it was coerced. The detectives denied it.

Lawyer Sam Silver, representing Wright, asked Devlin to write down the nine-page confession in real-time, as he said he had done “word for word” in 1991. The once-famed detective — who helped nab a New Jersey rabbi in his wife’s murder-for-hire — jotted down only six words before giving up.

Wright told jurors that police had made him sign the confession without reading it. They deliberated just a few minutes before acquitting him, and Wright, who spent 25 years in prison, later received a nearly $10 million settlement from the city.

“That case was remarkable. There was a DNA exclusion, and they said they were going to try it anyway,” said Maurice Possley, a senior researcher at The National Registry of Exonerations.

Santiago and Devlin are accused of lying about the confession. Santiago and Jastrzembski are accused of lying when they testified that they didn’t know about the DNA problem. Jastrzembski is accused of lying about finding the victim’s clothes in Wright’s bedroom.

All three maintain their innocence, and about a dozen aging friends — including some of the more illustrious detectives of their era in the Philadelphia Police Department — were in court to support them Friday.

Krasner has championed 47 exonerations to date while pursuing a small number of police perjury cases. He charged the Wright detectives in 2021, days before the five-year deadline expired.

The registry’s work shows that public agencies across the U.S. have spent more than $4 billion to compensate people for the nine years, on average, they wrongly spent in prison.