The Department of Human Services is understaffed and the primary culprit is low starting salary and overwork, says the union representing Philadelphia’s child protective service employees.

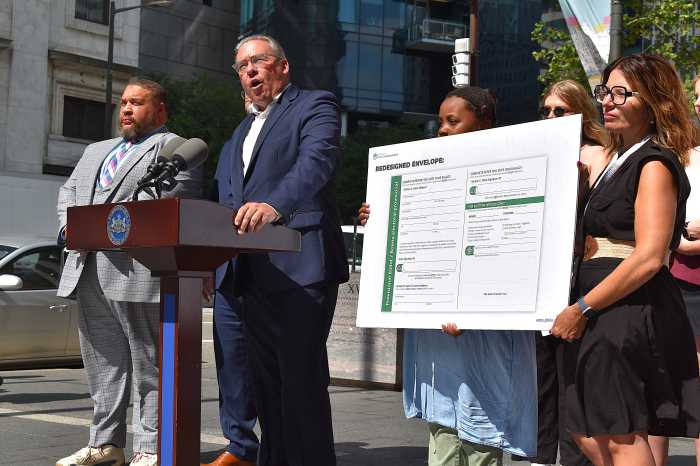

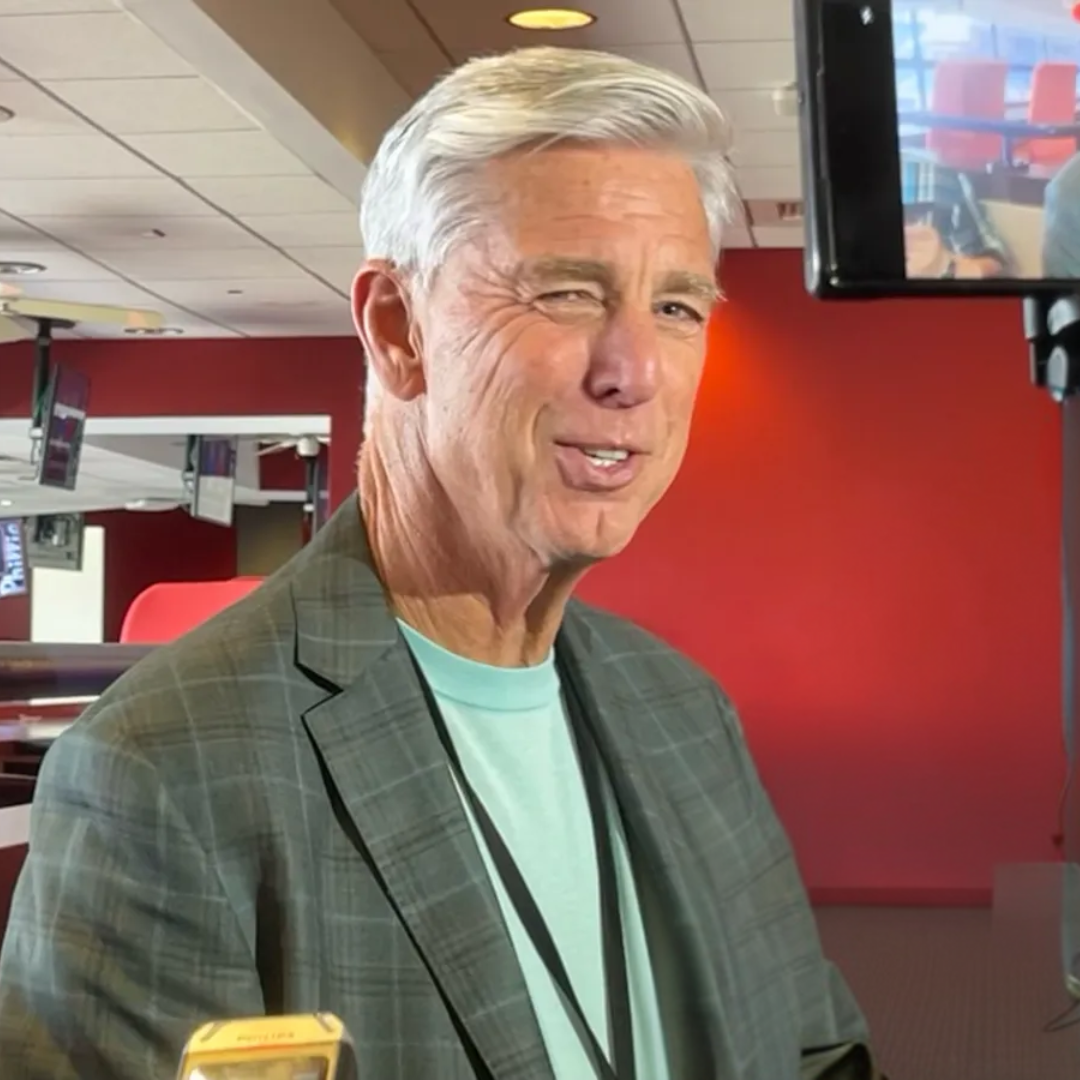

“They’ve got our workers doing too much,” says David Wilson, President of AFSCME Local 2187. “Because we’ve got policies that force our workers to go above and beyond state requirements in terms of the depths of the investigations they’re performing.”

This statement from the city’s union representing child welfare investigators will be particularly welcome to child welfare system reformers. Last year, a committee organized by City Councilmember David Oh issued a report that found the city’s Department of Human Services had generated massive distrust in the community by over-policing families.

The department’s labor troubles peaked this week when an email was sent out from DHS Operations Director Carla Sanders to staff, notifying hotline workers that they would be responsible not only for taking calls, but also conducting some investigations.

“The department still has over 100 cases requiring assignment for investigation,” reads the email, obtained by Metro Philadelphia. “Executive leadership continues to examine strategies to adjust to the rise of cases and the staffing shortage that significantly impacts child welfare nationwide. An immediate solution must be developed to address cases requiring assignment and thus addressing public safety. So I am announcing that all eligible hotline staff will receive at least two investigations for an assignment starting today.”

Wilson calls the move “crazy,” requiring staff charged with answering phones to conduct investigative work after what he calls “quick” training or refreshers for inexperienced or rusty workers.

A DHS spokesperson, in an emailed response to questions for this story, states that the department has recently assigned “some of our hotline staff, who are also trained as investigators…one report to investigate.”

The DHS official pegs the current vacancy rate among the “social work services job class” at 25-percent, a figure well beyond the industry goal of 10-percent. The union, however, says the investigations staff is particularly hollowed out, falling from around 230 people at pre-pandemic levels to about 145 now, leading to the current backlog of cases.

Staffing shortages are a historically persistent problem throughout the child welfare industry, but are peaking currently, worrying child safety advocates like Cathleen Palm, founder of the Center for Children’s Justice.

“Any kind of move relying on people who do not feel fully trained to conduct an investigation is a concern,” says Palm, “and it’s right for people to be on guard here.”

But she says the problem goes beyond DHS to the state government.

“This isn’t Philadelphia’s problem, this is 67 counties’ problem. There has to be a state lens to say: ‘Why is this not a state wide priority?’”

Palm suggests a recent proposal by Gov. Josh Shapiro to provide a tax break for police officers, nurses and teachers, should be expanded to child welfare workers, who tend to be forgotten first-responders.

An Inquirer story published late last year described a spiking workforce turnover rate in the city’s community umbrella agencies—a network of private, contracted providers which deliver services to kids and city families after DHS investigations are complete.

This month, DHS commissioner Kimberly Ali announced that in response to that crisis, she would utilize this spring’s budget sessions to boost the average salary of CUA case managers by 25-percent, to $60,000.

Wilson calls the timing “inappropriate” given the crisis in-house, and attributes the current vacancy rate to multiple factors, including general labor market upheaval after Covid-19, low starting pay and extraordinarily difficult work.

Pay rates for DHS social workers start at about $43,000 and scale up to $72,000 over the years. But that low starting salary and long hours, says Wilson, drive many workers away.

“The job is immense, he says, “and Philadelphia makes it harder than it needs to be.”

In other Pennsylvania counties, he explains, a worker investigating a call about a child with too-little food might discover the child is healthy, the refrigerator is full and immediately close the case.

“In Philadelphia,” he says, “workers have to go to the home twice and mount a full investigation, digging into things we weren’t called out for.”

Child advocates around the country have noted double standards that exist in child welfare, which disproportionately investigates and separates Black families. For example, suburban and usually white moms who smoke marijuana are largely accepted and even celebrated in popular culture, yet a Black mom with less money, living in the city, can wind up in a case with DHS, facing allegations about marijuana use in a battle to keep her kids.

In Philadelphia, Black people comprise 42 percent of the population and more than 60-percent of those in foster care.

Wilson says these more onerous investigations were instituted after the tragic 2006 death of Danieal Kelly, a 14-year-old girl with cerebral palsy who died of starvation and neglect.

Temple law professor Sarah Katz, who directs and teaches the family law clinic, says that “On a very base level, we oversurveil families like we’re on a fishing expedition. There is such tremendous distrust of DHS in the community because the families are treated with such tremendous distrust.”

DHS has made significant strides in recent years with a right-sizing initiative that has lowered the number of youth in foster care by 35-percent, but it maintains higher rates of removal for children in poverty than other big cities like New York and Chicago.

The union repping DHS’s investigative workers is expected to file an unfair labor practice complaint with the Pennsylvania Labor Relations Board next week for allegedly violating a bargained agreement on work assignments, which the union contends should have prevented the unilateral assignment of cases to hotline staff.

The DHS spokesperson wrote that the agency is “reviewing” the current requirement for making at least two visits with the child during an investigation.

The department is also continuing to work with the city’s office of human resources—which sets pay rates—to examine the pay scale, and a recruitment effort is underway to hire new workers.

“My people are drowning,” concludes Wilson. “My people are overworked and overburdened. It’s time we stop being fearful that every Philadelphia parent can’t parent their own children, and stop digging through their lives when that’s not what we were called out for, and then maybe DHS employees can be productive and happy, and won’t be thought of in the community as villains.”

Metro Philadelphia is one of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on economic mobility. Read more at brokeinphilly.org or follow on Twitter at @BrokeInPhilly. Our Kids is a project of the Broke in Philly reporting collaborative examining challenges and opportunities facing Philadelphia’s foster care system. Steve Volk is an investigative solutions reporter with Resolve Philly.