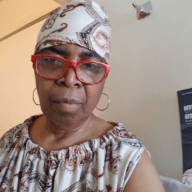

Karen Ali was still lightheaded Wednesday, even after she began eating again.

The 72-year-old who lives in senior housing in West Philadelphia had gone about 10 days without food.

She is part of a group that has been on a hunger strike in an attempt to pressure Gov. Tom Wolf to release more prisoners during the coronavirus pandemic.

Ali’s husband, Omar Askia Ali-Sistrunk, 74, has been incarcerated for 49 years, though he and Ali believe his murder conviction should be overturned.

He was sentenced to life in prison in connection with the infamous 1971 robbery of Dubrow’s Furniture Store, which ended with one person dead and another shot.

Ali said she and her husband are working with multiple organizations to clear his name. Given Omar’s age, he’s at a higher risk for developing severe complications from COVID-19.

“If that virus hits there, then that’s the death sentence right there for him,” Ali told Metro. “That’s how I feel.”

Ali, in consultation with medical professionals, decided to break her strike to protect her health, but about a dozen activists are still fasting as part of what’s called the “Free People Strike.” A total of about 25 have participated, and an additional 40 to 50 have joined in one-day “solidarity fasts.”

One woman has been fasting for 21 days, only breaking it for a meal once a week.

It’s more of a rolling strike, said Kavita Goyal, one of the other strikers, with people stepping in and out. Some have family members on the inside, and others have no personal connection to the jail system.

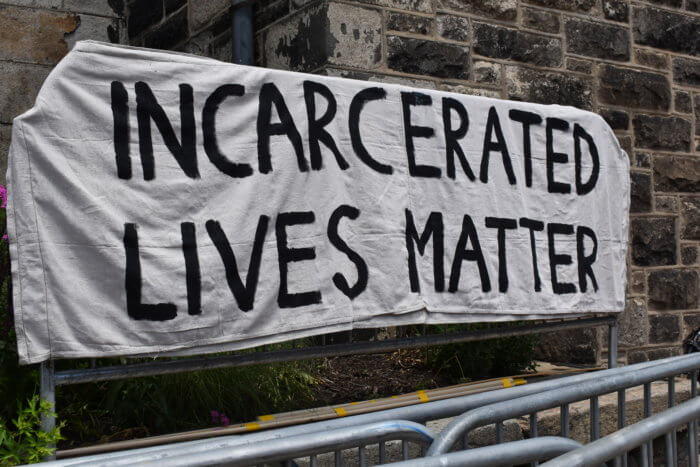

The initiative began May 28, and organizers held a demonstration earlier this month that drew a large crowd to Eastern State Penitentiary.

Their main goal is to accelerate the release of inmates, particularly the elderly and those with pre-existing conditions, and expand the state’s criteria for early release during the pandemic.

“We’re talking about nonviolent offenders,” said Patricia Vickers, an advocate from West Philadelphia. “We’re talking about elderly, like 60, 70, 80 years old. We’re talking about people with preexisting conditions. It just seems like a no-brainer to me when other states have let thousands go.”

Only 146 inmates have been let out as part of a reprieve program Wolf announced in April amid concern that state prisons would become hotbeds for the virus.

The program applies to inmates who are set for release within the next nine months and those who are scheduled to be freed over the next year if they are elderly or have certain medical conditions. It only applies to nonviolent offenders.

Initially, Wolf’s office said 1,500 to 1,800 inmates would be eligible for reprieve, though officials acknowledged the final tally of those released would likely be lower.

Wolf must approve any releases recommended to him by the Department of Corrections in conjunction with local district attorneys, the state Attorney General’s Office and the courts.

Nearly 42,000 people are incarcerated in Pennsylvania. Prisoners who are allowed out must serve the remainder of their sentences after the pandemic.

The slow process has angered advocates.

Goyal, who noted the governor has power to release prisoners, accused Wolf of shirking responsibility.

“What he did, which I believe was so cowardly, was he left the final decision up to other people, even though he didn’t have to,” she said.

Wolf’s office did not respond to questions Monday about why so few inmates had been granted a reprieve.

Late last month, state Corrections Secretary John Wetzel told WHYY that the process had been “more complicated” than expected.

Free People Strike leaders said their cause intersects with protests against police brutality that erupted in Philadelphia three weeks ago following the death of George Floyd.

Ali compared the effects of mass incarceration to the “knee on the neck” of Floyd, who died at the hands of police in Minnesota.

“We saw how that went down, but we didn’t see how they were using the court system, the legal system,” she said. “People didn’t understand that these things were going on and going on intentionally to separate families, to break up families.”

In Pennsylvania, ten state prison inmates have died from coronavirus complications, and 237 have tested positive, according to DOC data. One prison staff member has died, and about 180 have self-reported they were infected with the virus.

Correctional facilities have been conducting more cleaning and providing masks to employees and inmates. The DOC has also arranged more than 67,000 virtual visits for prisoners with family and friends.

Dee Dee Haw, who has been fasting for five or six hours a day as part of the strike, recently had a virtual conversation with her 44-year-old son. He is locked up at SCI Smithfield, serving a life sentence for second-degree murder.

She’s happy no Smithfield inmates have tested positive for the virus but is worried because SCI Huntingdon, which is down the road, has been among the prisons hardest hit by the pandemic.

Haw, who lives in Kensington, said Wolf has “put prisoners on the back burner.”

Vickers has not been fasting but is supporting the Free People Strike in other ways. Her son, Kerry “Shakaboona” Marshall, a former juvenile lifer who is serving time for murder, is not eligible for release.

“While I care for my son, I care for all the men and women who are in prison who may die for no good reason,” she said. “This is a time when you should be thinking of people as human beings.”